Race and Violence in American Prisons

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, December 12, 2014

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

David Skarbek, The Social Order of the Underworld: How Prison Gangs Govern the American Penal System, Oxford University Press, 2014, 224 pp.

Prisons are extraordinary laboratories for the study of human nature. How do impulsive, violent men behave when they are forced to live together for years on end in regimented intimacy? David Skarbek, who is a lecturer at King’s College, London, shows in this remarkable book that racial segregation is one of the basic ways American prisoners order their lives. Segregation is one of the key features of prison gangs, which have become so powerful that, at least in some states, they control virtually every aspect of prison routine. Dr. Skarbek argues convincingly that the purpose of prison gangs is to make and enforce rules, and that gangs are, on balance, a good thing.

The rise of prison gangs

Prisons are made up of groups of people and therefore need rules. Before the 1950s, there were no prison gangs to establish rules. Guards set rules, but their rules could not govern all kinds of prison behavior, especially since guards exercise power in direct opposition to many of the desires of prisoners. Therefore, before the appearance of gangs, prisoners supplemented prison rules with a convict code that Dr. Skarbek says has been essentially universal in all prisons everywhere. The most important part of the code is that convicts will not help guards in any matter relating to discipline; they will not inform on other inmates or interfere when they break prison rules. The code also forbids theft or violence between inmates.

Prisoners enforce these rules themselves. Violators may be shunned or, if necessary, beaten. For serious infractions, such as informing, an offender may be slashed across the face with a makeshift knife. That leaves a permanent scar that marked a man as untrustworthy.

For a code of conduct to work, prisoners have to know each others’ reputations. They have to know who is untrustworthy and who therefore should be shunned or punished. A system based on reputations can work only in a small population — thousands of people cannot keep track of each other — and it works best in homogeneous groups that have the same norms and expectations.

In prisons that operate by the code, men may form loose groups of four or five based on common interests or experiences, but these groups are very different from modern prison gangs. They are not exclusive, they do not have formal hierarchies, they do not usually have any existence on the outside, and they do not have any real influence on how a prison is run.

Dr. Skarbek argues that gangs appeared because prison populations in Texas, and especially California, changed so greatly that the old norms-based code no longer provided enough order.

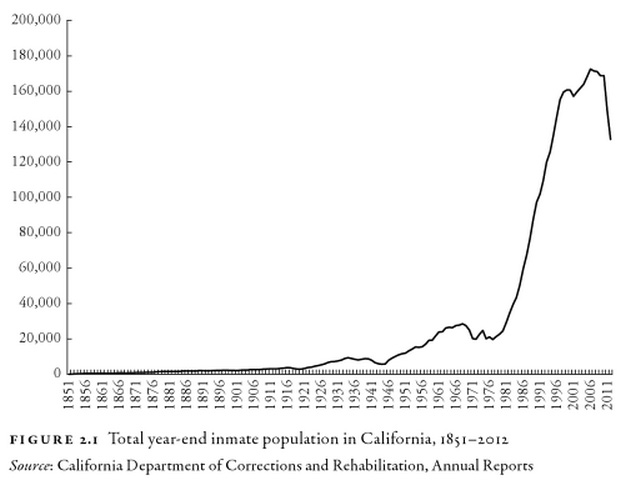

One big change was a huge increase in prisoners. From 1945 to 1970, the number of California inmates grew from 6,600 to 25,000, an increase of almost 400 percent. By the mid 2000s, the figure was nearly 180,000.

In such a large population, no one can keep track of who is or isn’t trustworthy. Also an enormous influx of new people who had no experience with the convict code made it much harder to enforce. The proportion of young offenders and violent offenders also rose, and it is harder to get young, violent men to respect norms.

At the same time, the prison population turned non-white. In 1951, there were two whites for every non-white in California prisons, but by 2011, there were three non-whites for every white. In the 1950s, people of different races congregated with each other but there was not much racial tension. Tension rose as the inmate population shifted to non-white, and as the social turmoil of the 1960s entered prisons. The prison code broke down, and there was an alarming increase in violence.

All these changes meant inmates needed new rules and ways to enforce them, but something else also contributed to the rise of prison gangs: drugs. Dr. Skarbek writes that by 1978, as many as 82 percent of California inmates were addicts who had to have drugs. Where there is demand there will be supply, and a brisk trade in drugs sprang up in prisons. Convicts used to buy drugs from each other with cigarettes, but after California banned cigarettes, postage stamps became currency.

How do drugs get into prisons? New prisoners smuggle them in, accomplices on the outside throw them over the fence, and visitors bring them in, but the largest source is corrupt guards.

Pushing drugs in prison is not a one-man job. Customers are likely to kill a sole proprietor and steal his drugs. They may kill him instead of paying off a drug debt. If the dealer is part of a gang, however, the gang can be counted on to take revenge, and that discourages violence. Gangs also punish people who shortchange customers or sell shoddy goods. Gangs want repeat customers, so they maintain quality. Gangs thus keep order, police quality, and supply a product inmates need.

The initial reason prison gangs were formed, however, was for protection from the violence and chaos that followed the changes in the prisoner population that destroyed the old convict code. The very first prison gang was reportedly the Mexican Mafia, which appeared in 1957. They needed to defend themselves from stronger blacks and whites who were pushing them around, but after Mexicans got organized, they began to prey on other races. In 1967, white prisoners established the Aryan Brotherhood to protect themselves from Mexicans, and the Black Guerrilla Family formed at about the same time for the same reason.

The Mexican Mafia, also known as El Eme (“The M”), was mainly from Southern California, and it preyed on northern Californian Mexicans as well as whites and blacks. Mexicans from northern California responded by setting up Nuestra Familia (Our Family). These gangs arose in prison, and were not imported street gangs. They are classic examples of the tribal, mafia-style organizations that spring up when there is no authority to maintain law and order.

Prison gangs are concentrated in California and Texas, which have large, mixed-race prison populations. Dr. Skarbek writes that 70 percent of members are in those two states.

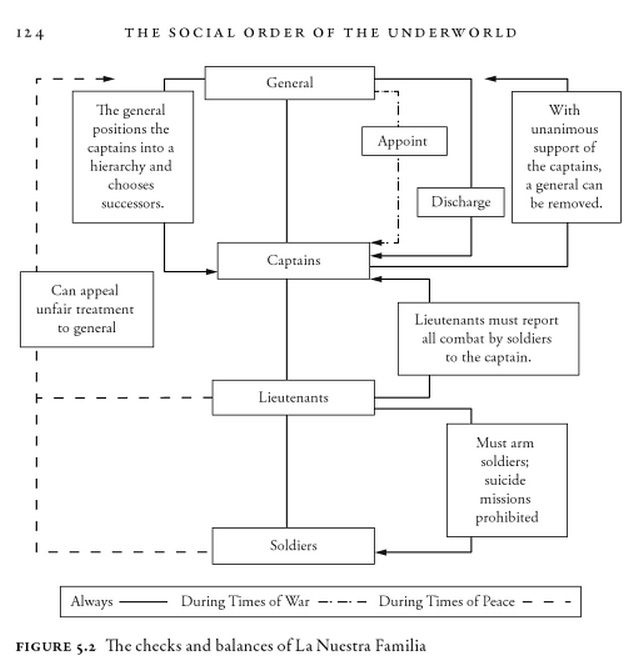

Prison gangs are hard to study because they often have codes of silence, and even when members break silence they cannot always be trusted. However, it is clear that prison gangs are not like street gangs. They are more highly organized, more strictly disciplined, and require lifetime membership. They have formal rules and even written constitutions that define levels of authority, responsibility, and duty. People in authority have various formal names but are known informally as shot-callers. This illustration shows Nuestra Familia’s formal organization.

Gangs are segregated in the most obvious way — by race — and race permeates every aspect of prison life. The balance of gang power determines the order in which the different races go through the chow line, what parts of the prison yard are their exclusive territory, which benches people can sit on, who can use weights or basketball courts at what hours, etc. If a gang is strong enough, it may charge a fee to let inmates of other races lift weights or play basketball. The most powerful gangs stake out the parts of the day rooms and prison yards that are least visible to guards, where drug deals and other shady business is easier to hide.

Inmates must socialize only with people of their own race. They must have their hair cut by someone of their race, using clippers that have never touched the head of someone of a different race. The only thing that crosses racial lines is contraband; inmates may buy drugs or alcohol from anyone.

One of the cardinal rules of prison gangs is that if there is a fight between inmates of different races, everyone pitches in to defend his race. However, riots are a last resort that everyone wants to avoid. Drug dealing, and the money that can be made from it, are very important to gangs, and violence is bad for business. As one gang member explains:

We don’t fight in a riot and stuff unless we have to, it’s too dangerous. We’ll go into lockdown, which sucks, and people get killed and stuff. If I’m in lockdown I’m not working. You can make some serious bank in prison and shot-callers hate it when you’re in lockdown.

Gangs enforce discipline best when every inmate is, if not a formal or “made” gang member, at least affiliated with a gang. Mavericks are a menace, because they are not subject to gang discipline. Each inmate, at least in California prisons, must therefore affiliate with a gang of his race and be subject to its discipline.

Gangs keep the peace. If a black, for example, gratuitously offends a white or a Mexican, his gang disciplines him. He may be forced to apologize or be made to run laps in the yard, where everyone can see. For serious offenses — violence, for example, or welshing on drug debts — the black gang may turn the offender over to the aggrieved man’s gang for a serious beating. This will take place out of the sight of guards, in a cell or in a blind corner of the prison yard. The beating victim will not, of course, complain to guards because that would result in even worse punishment.

Some disagreements can be settled only by single combat, but this must not take place spontaneously in the prison yard, where it would attract the attention of guards and could start a riot. Gangs arrange for two men to meet in a discreet location and slug it out.

Controlling violence in this way is a great benefit for prisoners. Dr. Skarbek reports that in California, prison homicide declined 94 percent between 1973 and 2003, at which point it was lower than for people on the outside. Prison riots have also declined greatly since the 1970s. Most prisoners join gangs or affiliate with them, not because they want to make trouble but because they want to avoid it.

Guards take credit for declines in violence, but Dr. Skarbek thinks the real reason is gang discipline. He points out that guards don’t like prisoners, some of whom insult or assault them, and many don’t care if prisoners kill each other.

A gang does not have to have many formal members in order to wield great influence. The most powerful gang in California and Texas prisons, the Mexican Mafia, is estimated to have only 150 to 400 official members. They are intensely loyal, and act immediately and without question on orders from superiors. The only way to leave the gang is death. New members are chosen very carefully, and any member can blackball a recruit. Someone who recommends a new member is fully responsible for his actions, so if the new member fails in his duty, the man who recommended him must kill him. Gang members are required to spend a certain amount of time every day working out so they can be fit, capable soldiers. “Made” members are the nucleus that disciplines affiliates of the same race who are not actual members.

One of the greatest surprises about prison gangs is that they have extensive influence beyond prison walls. The Mexican Mafia, for example, levies a tax on drug sales by California street gangs outside prisons. El Eme can do this because sooner or later members of street gangs are going to end up in California prisons, where they are at the mercy of the prison gang. If a street gang has not been paying the tax, the Mexican Mafia puts out a “green light” on that gang, meaning that any member is to be attacked on sight. This is a very credible threat to anyone who ends up in a California prison.

Many California street gangs are therefore officially affiliated with the Mexican Mafia and pay taxes to it. Gangs that have the number 13 after their names, such as MS-13 or Florencia-13 are openly advertising their affiliation with El Eme — “M” is the 13th letter of the alphabet. This is a strong signal to competitors that a gang has the support and protection of the most powerful prison gang in America. It’s a warning to other gangs to keep out of their turf.

The Mexican Mafia wants peace and quiet on the outside as well as in prison, because it is better for business. At one point it ordered California gangs to stop doing drive-by shootings because they made the news, scared customers, and brought in the police. The number of drive-bys dropped.

El Eme also doesn’t like intra-Hispanic violence if it can be avoided. As one prisoner explains: “It’s about making money nowadays, not shooting your own raza up. If you guys wanna shoot somebody go shoot up those niggers from Westside 357 or Ghosttown.”

There are limits to El Eme’s reach. It can tax gangs only in California because only California gang members are imprisoned in California and therefore vulnerable to punishment. Also, it can tax only Hispanic gangs because it cannot easily put the green light on a white or a black. Interracial violence — unless it is cleared beforehand as a form of just punishment — can start a riot, which everyone wants to avoid.

Naturally, some Hispanic street gangs resent paying the drugs tax to the Mexican Mafia. For a while there was a gang that called itself the Green Light Gang and openly advertised the fact that it did not pay taxes to El Eme. Dr. Skarbek notes dryly that many of its members ended up dead.

Drug taxes add up. An Eme shot-caller may collect as much as $50,000 a month. It used to be very easy for California inmates to handle this kind of money; they had official convict bank accounts. The prison system finally got wise to how the accounts were being used, and started monitoring them for big transactions. Now, it is often wives and girlfriends of jailed Eme members who collect and bank the taxes.

It is useful for gang members to be easily identifiable. A man who is obviously a gang member can speak for the gang, and if he is transferred to another prison his status can go with him. That is why members get tattoos. A “made” member of El Eme or Nuestra Familia has a lot of authority, inside a prison and out, so criminals may be tempted to fake membership by getting gang tattoos. A properly run gang kills impostors.

It takes a lot of information to run a gang. Shot-callers need to know whether underlings — sometimes in other prisons — are following orders. They need to know when a street gang member who deserves punishment is going to prison — and where. They need to know who is behind on drug debt or needs to be taught not to push low-grade drugs. There is therefore a huge traffic in smuggled cell phones, once again mostly by corrupt guards.

In 2011, California prison guards confiscated more than 15,000 cell phones from prisoners. A study that used sophisticated electronics once detected more than 25,000 phone calls, texts and Internet accesses from a single prison in just 11 days.

Dr. Skarbek thinks prison authorities are not handling gangs correctly. Guards try to decapitate gangs by putting shot-callers in “administrative segregation,” which is the fancy new word for solitary. That just opens up spots in the gang hierarchy for new men. Gangs meet important convict needs, and until those needs are provided some other way, gangs will meet them.

Prison gangs are a crude but effective way in which men have banded together to provide order in a lawless environment. Gangs took on their present form through trial and error, not through deliberate design. They are a fascinating example of spontaneous, purely pragmatic, human organization. And they are particularly clear evidence that man’s tribal nature instinctively expresses itself in the form of racial segregation.