Clockwork Orange France

Rémi Tremblay, American Renaissance, March 15, 2013

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

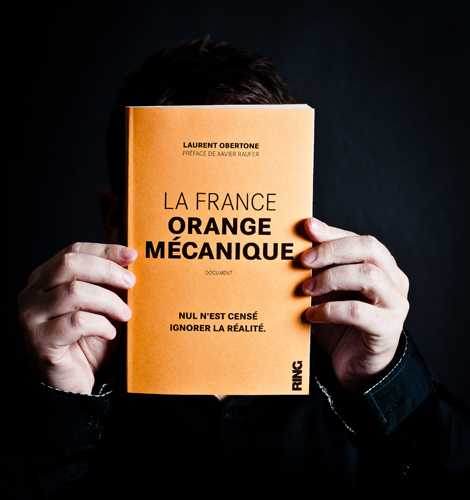

Laurent Obertone, La France Orange Mécanique, Ring, 2013, 350 pp.

La France Orange Mécanique (Clockwork Orange France) became an instant best seller in France, finding itself in the top-ten list on Amazon.fr despite no advertising and a virtually unknown author. Even in a climate of reduced book sales, the publisher, Ring, has recently had an additional 18,000 copies printed. Some reviewers note that if this book — which describes the true face of crime in France — had been published before last year’s presidential elections, it might have had an impact on the outcome, swaying votes towards the Right.

The book, whose title refers to the 1962 Anthony Burgess novel about “ultra-violence,” begins with an all-too-common event: a white woman is savagely beaten and raped almost to death by a foreigner. This gruesome rape is presented from the victim’s perspective, allowing the reader to grasp the horror of the situation — a horror that can be washed away in a sea of statistics: 7 percent of French women are raped at some point in their lives, and there are 13,000 thefts, 2,000 assaults and 200 rapes every day in France. Behind these statistics, there are personal dramas and shattered lives. For each crime, there is a life that will never be the same. This is what Laurent Obertone wants us to remember: Crime is not a matter of numbers; it is devastating trauma.

Beyond the crime statistics, many lives are ruined by daily harassment from immigrants, but victims get no support from society and resign themselves to their fate. They suffer from depression, fear, and even suicide, but they never appear in official reports: They will be forgotten and ignored.

In pointing out how heavily concentrated crime is among immigrants, Mr. Obertone breaks a major taboo. He is frank about the vast overrepresentation of Gypsies and North Africans in French prisons. In France, there are no official statistics about ethnicity and crime, but there are figures for the number of foreigners in the prison system (22 percent). These statistics are skewed because an Arab born in France is considered a Frenchman. Ironically, Mr. Obertone has to cite a study reported in the Washington Post to conclude that between 60 and 70 percent of the prison population is Muslim.

Mr. Obertone has also found local racial statistics on crime for some towns and cities, which confirm the overrepresentation of non-whites in prison. He shows that this not a uniquely French phenomenon; in European countries blacks and Arabs are always overrepresented in the criminal population. He makes an air-tight case for what everyone knows but dares not say: The explosion of crime is directly linked to immigration.

France is, indeed, becoming one of the most dangerous of all Western societies: 1,200 homicides each year and 1,000 attempted homicides. Crime now costs French citizens 115 billion Euros each year — twice the revenue generated from income taxes. Common criminals now confront police with automatic rifles and assault weapons, once used only by organized crime.

Police officers themselves are victims of harassment and open provocation by criminals, but receive no support from the media or authorities. When they enforce the law they are routinely accused of “racism.” Mr. Obertone reports that the police union now says offices are afraid to use force, for fear of racial consequences. Criminals therefore no longer fear the police, and their authority is further diminished when criminals get limited or no jail time. There are few deterrents to crime and criminals know it.

This undoubtedly explains why race riots in France are more frequent and violent than in any other European country. The authorities have surrendered to blackmail and have invested billions of Euros in some 700 “sensitive neighborhoods,” proving that the more you destroy, the more you are rewarded. Police rarely enter these neighborhoods for fear their mere presence could be a “provocation.” Mr. Obertone says that the media and politicians nevertheless blame the police for the high percentage of immigrants in jail. The only accepted explanations are discrimination and profiling.

The French judiciary system is like that of the United States in the 1960s and ’70s: the emphasis is on prevention and rehabilitation. For French sociologists and so-called experts, it is still the fashion to blame society exclusively for crime. The focus is thus on compassion for the culprit, with no regard for the victim. Basically, only recidivists are sentenced to prison, and prison terms are often suspended.

In France, 2,250 women have been raped by recidivists. According to Mr. Obertone, the real number is considerably higher, because some rapists are never caught and because some rapes are classified as “sexual assaults” and are therefore not counted as rape.

Even with low incarceration rates, prisons are at 117 percent of capacity. Socialist politicians block the construction of new jails, which they would see as an admission that society is failing. Only in the 1980s and 1990s did Americans come to realize that long prison terms are what keep a society safe.

The media hide the reality of crime in France, using euphemisms to talk about the few events they dare to mention. Criminals are “youths,” even if they are in their twenties, and savagery is sanitized with such terms as “aggravated assault” and “sexual assault.”

The government helps cover things up, launching campaigns for traffic safety and condemning domestic violence against women, although these phenomena are statistically insignificant. These campaigns detract from the real problems, and suggest a lack of political will to solve them. On the political front, everyone is silent. The Right is afraid of the Left, and the Left is afraid of the truth.

And yet, there are crimes the media and politicians are happy to discuss: those against certain minorities. Fighting anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and homophobia are important priorities, and the government spends a great deal of money trying to eradicate these evils. However, Mr. Obertone notes that only 0.03 percent of the Muslims, 0.06 percent of the Jews, and 0.007 percent of homosexuals are reported victimized each year. Why single them out, when a far larger percentage — 0.7 percent — of French natives are victimized each year? Despite what the media and politicians say, it is safer to be a Jew, a Muslim, or a homosexual than to be an ordinary Frenchman. Needless to say, minor acts committed against minorities are huge stories, while luridly racist crimes committed against whites are downplayed or ignored.

Mr. Obertone writes that most of the French seem to have fallen asleep in front of their TV sets and shut themselves off from what is happening in their country. Even when they realize something is wrong, they are afraid to speak up, afraid of being called a racist and thus risking their livelihoods. As it is everywhere in the West, anyone accused of racism is guilty until proven innocent.

In France there is a myriad of antiracist groups that play the role of “thought police,” and ensure that no one questions the system. These groups, generously subsidized by the government, target only one type of racism and are completely blind towards anti-white racism — even though today, one French native in ten considers himself a victim of racism.

In his discussion about the cause of crime, Mr. Obertone refers to IQ without explicitly mentioning race. He explains that the average unskilled worker has an IQ of 92, and that the great majority of Arabs are working class. Thus, we cannot expect the same results from them as from French natives. His logic is a simple way of implying racial differences without stating them bluntly. Candor on these matters can bring criminal charges.

Despite the serious nature of the topic of this book, the tone is sometimes humorous. The author is not overly academic or sensationalist, and the book is easy to read despite its liberal use of statistics. Mr. Obertone does not make utopian promises about stopping crime; he simply presents a realistic portrait of a situation deliberately ignored by the media and politicians. But the mere appearance of a book of this kind and the reception it has received are grounds for celebration.