James J. Kilpatrick: Journalist, Southerner — Sellout?

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, August 23, 2013

William P. Hustwit, James J. Kilpatrick: Salesman for Segregation, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013, 310 pp.

James Jackson Kilpatrick, Jr. (1920 – 2010) was a hugely popular conservative commentator of the latter part of the 20th century. Thanks to television, he became one of America’s first “celebrity journalists” and, with William Buckley, personified the Right. Before that, however, he was one of the country’s best known segregationists.

How did he make the switch? Did he change his views? Sacrifice his principles? A little — or a lot — of both? William Hustwit, who teaches history at the University of Mississippi, has written a biography of Kilpatrick that tries to answer these very questions.

Defender of the South

Although Kilpatrick lived for many years in Richmond and considered himself a spokesman of the South, he was born and raised in Oklahoma. His ancestors were Southerners, however, and Kilpatrick, Sr., whose name he bore, got the middle name of Jackson in honor of Stonewall Jackson. The father was a libertarian who thought government should get out of the way. He flouted prohibition laws, and this defiance of authority made a deep impression on his son. The family suffered during the Depression, which was a harsh, early lesson in the importance of hard work and self reliance.

Young James was a precocious boy — he was reading the Decameron at age five — and he and his brother and sister spent hours quoting lines of poetry to each other. He was editor of his junior-high and high-school newspapers, and never doubted that he would be a newsman. Kilpatrick graduated from high school at age 16 and studied journalism at the University of Missouri, where he got the nickname “Kilpo,” which stuck with him for life. In 1941, just out of college, he got a job with the Richmond News Leader, where he was to work for 25 years. He tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps but was rejected because of asthma, and as other newsmen left for the war, he took on greater responsibilities.

When he first came to the News Leader, he did not have well defined political views, but the paper’s publisher, John Dana Wise, gave him a thorough education in Burke, Calhoun, John Randolph of Roanoke, and Russell Kirk. Kilpatrick began calling himself “an 18th century liberal” or a “Whig,” and began to fear, as he put it, that tyranny would come from a federal government that would become “more expansive and more mild” and “would degrade men without tormenting them.”

In 1950, at age 30, Kilpatrick became the editor of the News Leader, as well as its main editorial writer. He wrote an astonishing 10,000 words a week — half a million a year — and developed a vigorous style partly modeled on that of H. L. Mencken. His chief enemy was Washington: “The more I meditate upon the bloated thing our federal government has become, the more convinced I am that only drastic surgery will save us.” He laughed at the idea of equality, and believed Southern blacks were content with segregation. He thought the Klan was rabble, but he honored the Confederate Battle Flag as a symbol of “individual independence from the massive socialist state.”

He first came to national attention in a surprising way. He had immersed himself in the case of Silas Rogers, a black man convicted of killing a policeman. He found inconsistencies in the trial transcript, hunted down witnesses the defense had overlooked, and became convinced Rogers was innocent. He started a campaign for Rogers that convinced the governor to pardon him in 1953, earning Kilpatrick national praise and the accolades of the black press. Kilpatrick was furious when Rogers later raped a woman and went back to prison. “Sometimes you have to learn lessons the hard way,” he wrote.

The 1954 Brown decision galvanized Kilpatrick. For some time, he had been predicting big trouble from the Supreme Court, and he thought Earl Warren was a terrible choice as Chief Justice. And yet, when the court declared segregated schools unconstitutional, Kilpatrick was strangely calm, urging reflection rather than action. Later, he explained:

I think all of us in the South were intensely conscious at that moment that the whole country was looking at us, so in some excess of gentility, we were determined to be on our best behavior. Nobody likes to cry in front of strangers.

Kilpatrick shook off his “excess of gentility” and got to work on a two-pronged strategy: One was “interposition,” whereby the states could simply ignore the Supreme Court ruling, and the other was “massive resistance,” which meant shutting down the public schools and making state money available for private-school tuition.

“Interposition” was a legal argument based on the writings of Founders and other historical figures, who argued that state sovereignty meant states could ignore federal laws and court decisions they honestly believed to be unconstitutional. Kilpatrick republished entire speeches by Madison, Jefferson, and Calhoun, and added his own stinging commentary, calling the Warren court “a judicial junta that simply seized power.”

Kilpatrick wrote tirelessly, and his impassioned editorials were in great demand as pamphlets all over the South. He almost single-handedly made “interposition” a household word for perhaps the first time in US history. He flatly rejected the idea that interposition was outmoded. “Is Jefferson out of date?” he asked. “If so, the American Republic is dead.” He also denied that the Civil War had settled the question. Violence, he argued, is not a Constitutional argument. He consistently treated “United States” as a plural noun, as in “the United States are a republic.”

Kilpatrick believed states had a Constitutional right to secede, but kept that view private. He did, however, call for a fanciful Constitutional amendment banning segregation. Even if it passed Congress, rejection by Southern states would mean it would never be ratified, and the amendment’s failure would endorse the Southern way of life.

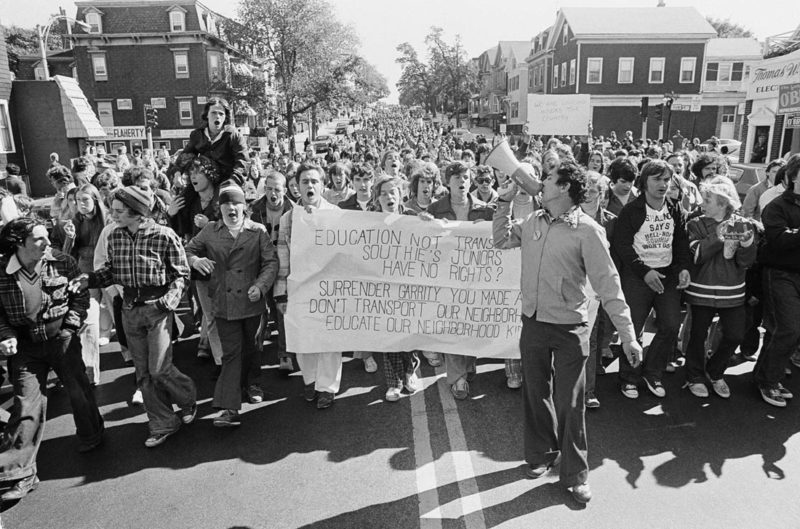

Behind Kilpatrick’s strategy was the delusion that if the South could hold out for just a few years, forced integration of schools in the North would be so agonizing for Yankees that they would see the wisdom of segregation. In the meantime, he tried to peddle interposition as a strictly legal, non-racial argument that appealed to all sections and rose “above the sometimes sordid level of race and segregation.”

That failed, of course. Everyone knew that race was the only reason Southerners suddenly started jabbering about interposition. Kilpatrick himself could not resist putting a chapter on race into his book, The Sovereign States, which was supposed to be about states’ rights. Published by Henry Regnery in 1957 and now available on the Internet, The Sovereign States is an impressively researched, closely argued book that still makes excellent reading. And Kilpatrick’s observations about race are still true:

In reading, in reasoning, in educational aptitudes, in all the standardized tests that produce an “I.Q.,” the median Negro at the eighth grade level customarily is found nearly three school years behind the median white. Is this deficiency to be blamed upon the quality of the South’s Negro schools? Basically, the same findings have turned up in the District of Columbia, where a bounteous Congress in times past provided the finest Negro schools on earth.

As a legal argument, interposition won over the South. By 1957, no fewer than eight states — Alabama, Virginia, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Tennessee — had passed resolutions of interposition rejecting federal authority to integrate schools.

But then came Little Rock. In 1957, Arkansas’s governor Orval Faubus cited interposition to justify sending the National Guard to prevent court-ordered school integration. Eisenhower sent in the 101st Airborne Division, and Faubus backed down. This was an enormous shock to Kilpatrick, who never expected Eisenhower to send troops, and it doomed interposition. “It looks mostly as if Reconstruction days are here again,” he wrote. He blasted Eisenhower as a tyrant, but that did not resegregate the schools.

With his legal arguments once again crushed by Yankee infantry, Kilpatrick — and Virginia — fell back on local remedies. Even after Little Rock, two out of three Virginia whites preferred to eliminate public schools rather than integrate them. Virginia called a convention to amend the state constitution and remove the requirement that the state operate public schools. The state government then voted to provide grants to Virginians so they could send children to private schools. Kilpatrick’s paper cheered lustily.

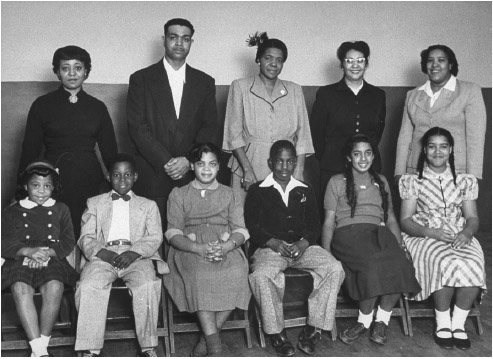

In the most celebrated example of “massive resistance,” Prince Edward County kept its public schools closed for five years. White families pitched in and built a new, private school, Prince Edward Academy. Kilpatrick raised money for the academy, and gave its library 10,000 books. Whites offered to build a school for blacks as well, but “civil rights” leaders rejected the offer, because they knew that idle black children were a potent symbol of “racism.” The county’s public schools were closed until 1964, when they were reopened by federal court order. (Prince Edward Academy continued to admit only whites, and lost its tax-exemption in 1978. It fell on hard times, changed its name to Fuqua School in 1993, and now admits blacks.)

In 1958, the Virginia legislature created the Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government to work with other Southern states to protect state sovereignty. Kilpatrick was made head of its publications department, and by 1969, when the commission closed down, he had distributed more than two million books and 16,000 pamphlets.

Again, however, the idea was to ignore race and educate the country about states’ rights. The commission kept its distance from the white Citizens’ Councils, and would not even let the publishers of Carlton Putnam’s Race and Reason — which was wildly popular in the South — use its mailing list. Kilpatrick wanted the commission “to stay absolutely free of the race issue.”

He found some support for his own writing outside the South, however, especially at William Buckley’s National Review, which supported segregation, and at US News and World Report, founded in 1948 by David Lawrence to oppose the New Deal. By 1957, he was becoming a national spokesman for both conservatism and segregation.

In 1958, Kilpatrick had a curious encounter with the Charlottesville, Virginia, Anti-Defamation League, which was distributing pro-integration literature. Kilpatrick wrote an editorial pointing out that if the ADL’s job was to fight anti-Semitism, it should stop stirring up dislike for Jews by meddling with popular institutions. Southern Jews who read the editorial swamped the Charlottesville office with mail, telling it to leave segregation alone. Kilpatrick had a meeting with ADL representatives, and they promised to keep quiet about Southern institutions.

Kilpatrick continued to believe that if the South could only hang on, the North would come around, both on states’ rights and on race. He urged Virginia’s governor, Lindsay Almond, to defy federal orders and let himself be arrested rather than integrate schools, but Almond was not made of such stern stuff. All across the South, politicians and school bureaucrats were submitting to the federal government, and Virginia followed suit.

Brown had integrated schools but nothing else. There was still legal segregation of private businesses in the South, and in 1960 black students started organizing “sit-ins,” in which they took seats at lunch counters, asked to be served, and waited for the police to arrest them. That year, there was a sit-in in Richmond, and Kilpatrick came by to see for himself. He was dismayed to find a group of well-dressed, well-behaved blacks being jeered by loutish whites. He correctly saw the sit-ins as a sign that blacks would not be satisfied with school integration alone.

Likewise in 1960, he had a television debate with Martin Luther King. There appears to be no copy of the video on YouTube, but a transcript can be found here. Even the most ardent King supporters had to concede that Kilpatrick dominated King with legal arguments that made King’s moral arguments look like whining.

Kilpatrick was furious about the fawning treatment King was getting in the Northern press, and complained about what he called a “paper curtain” that sealed out the Southern view of race and civil rights. He was disgusted when the Associated Press refused to cover a story about a gang of blacks who had raped a white woman. King’s 1963 march on Washington and the accolades it won were too much for Kilpatrick. He sent a piece to the Saturday Evening Post called “The Hell He Is Equal.”

The Negro race, as a race, is in fact an inferior race. . . .Within the frame of reference of a Negroid civilization, a mud hut may be a masterpiece . . . . But the mud hut ought not to be equated with Monticello. . . Where is the Negro to be found? . . . He is lying limp in the middle of the sidewalk yelling he is equal. The hell he is equal.

Shortly before the piece was to come out, segregationists bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and the Post’s editor decided not to publish it.

By this time, Kilpatrick could see the Civil Rights Act of 1964 coming, and helped found a lobby to try to stop it. Once again, however, the Coordinating Committee for Fundamental American Freedoms soft peddled race and tried to couch the argument in libertarian terms. As he wrote for National Review, if the “citizen’s right to discriminate” is destroyed, “the whole basis of individual liberty is destroyed.” He made the case with his usual verve in the very effective pamphlet, Civil Rights and Legal Wrongs.

Kilpatrick also predicted “affirmative action” before just about anyone else, warning that any ban on legal discrimination would mean preferences for blacks. The only way an employer could prove he did not discriminate was to hire unqualified blacks, who would have to be “petted and pampered, cuddled and coddled.” It was probably Kilpatrick who first applied the term “reverse racism” to this process.

The Coordinating Committee’s work, including ads in newspapers all over the country, probably contributed to George Wallace’s successes in the Democratic presidential primaries in states such as Wisconsin, Maryland, and Illinois, but Kilpatrick had nothing but disdain for the Alabaman. “We need thinking men and God sends us George Wallace!” he wrote. “It’s enough to make a man lose his religion.” He thought Wallace was “a vainglorious young blockhead,” and preferred the smoother Barry Goldwater. Goldwater was a dues-paying member of the NAACP who favored integration, but thought the federal government had no right to make it happen. Kilpatrick preferred this indirect approach to Wallace’s rough talk of “niggers.”

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was, of course, a terrible blow to Kilpatrick. About this time, he wrote, “In my blue moments I see nothing ahead for this country but the decline that inevitably awaits those who will not learn the history of mankind.” With legal segregation gone, he hoped and expected that whites would simply steer clear of blacks in their private lives. At the same time, the 1964 act had removed the last excuse for blacks. As he noted: “The Negro says he’s the white man’s equal; show me.”

National stature

It was in this same year, when everything he had worked for had crumbled, that Kilpatrick got an opportunity that changed his life. The Long Island newspaper Newsday offered him a column with a promise of syndication. As he saw it, his role was “to present to a national audience the reasoned and calm point of view of a conservative white Southerner,” but that meant toning down anything about race. Instead, he blasted welfare and the Great Society.

His column was a hit, and the conservative afternoon paper, the Washington Star stole him away from Newsday in 1965. The Star promoted him effectively, and by1966 he was in 100 newspapers. He left Richmond and moved to Washington, and gave up his last duties at the News Leader a year later.

Author Prof. Hustwit notes a very significant event in 1966. The Saturday Evening Post offered to publish the piece it had killed in 1963, but with a milder title, “Negroes Are Not Equal.” Prof. Hustwit, who had access to Kilpatrick’s private papers, quotes from his reply: “From my own professional point of view, the problem is quite simply that I do not want — and could not possibly afford — to be publicly associated with those views, phrased with such vigor.” Kilpatrick explained that publishing the piece would hurt his column. The Post had the publication rights, however, and Kilpatrick even offered to buy them back for $1,500 — a lot of money at the time — if that was what it took to bury the column.

As a national figure, Kilpatrick felt he had to trim his sails, though he still occasionally loosed his cannons on blacks. In 1967, he wrote: “[T]he law-abiding majority of this country, imperfect as it is, ought to put a hard question to large elements of the Negro community: When in the name of God are you people going to shape up?”

But mostly he backpedaled. When Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968 he astonished his old friends when he wrote that King “was the bravest man I ever knew in public life. . . . To watch one of his marches was to sense the awesome power of strong character combined with high purpose.” (He did manage to oppose the King holiday.)

It was television, however, that made Kilpatrick famous. He was a regular guest on Meet the Press, Inside Washington, and Agronsky & Company. He pioneered the idea of delivering not just opinions but personality. He understood that viewers wanted “a much more personalized journalism than tradition has permitted,” and carried around a makeup kit to make sure he looked good for the cameras. By 1980, his column was in 538 dailies and he had an annual income of more than $150,000. He was close to the Nixon White House, and the president sought his advice.

All this came at a price. By 1974 he was writing that the Brown decision had created “a far better America,” and in 1977 claimed he had overcome his “old-fashioned Southern racial prejudices.” Now, he said, he was just as incensed as anyone at “the virulent evils of a pervasive racism” that the federal government had wisely put down.

One thing he never backed down on was opposition to race preferences and to school busing. He liked to claim that he was now race blind whereas his opponents were still race-conscious troglodytes.

There were occasional flashes of the old Kilpatrick. In a television discussion of race preferences he asked a fellow guest, “How would you like to ride in an elevator constructed by an Eskimo, Chicano, or Black?” There were calls for his scalp, and he promised CBS he would apologize, but it is not clear that he ever did. In 1978, Kilpatrick complained that the 1965 immigration act was letting in a “tidal wave” of “racial and ethnic groups with little understanding of Western values,” but he does not seem to have thought very much about immigration. When Portuguese rule ended in Angola in 1975, however, he wrote that he “never feared for the black man at the hands of his oppressors half as much as at the hands of his liberators.”

In his private life, Kilpatrick escaped from the consequences of the changes he now claimed to accept. He built a house in rural Rappahannock County, Virginia, 85 miles away from Washington, where blacks were still deferential. He wrote in an elegant office with a zebra-skin rug, but fancied himself the successor to the Southern agrarian tradition. He wrote about the beauties of agriculture, the slow pace of rural life, and the spirit of the South.

Kilpatrick continued to write about politics, but in 1981 he started a column on English prose style, and his last three books were about writing. He became so divorced from his past that when PBS asked him for segregationist arguments to use in its documentary, Eyes on the Prize, he claimed he could no longer remember the ’50s and ’60s. In some cases, he simply lied. In 1988, he claimed he had sympathized with the sit-ins of 1960, and “ardently supported” the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Prof. Hustwit writes that Kilpatrick “still believed deeply in blacks’ inferiority,” but he offers only indirect proof. In 1985 Kilpatrick wrote privately: “I still regard interracial marriage as regrettable . . . . and hope that it always will remain an aberrant condition, to be tolerated in the name of a free society but not to be encouraged.”

In one of his last political opinions, no doubt fittingly, Kilpatrick completely reversed his earlier view of the role of the federal government in local decision-making. When the Supreme Court decided in 2007 that the cities of Seattle and Louisville could not use race as a criterion for balancing school populations, Kilpatrick rejoiced. What he once called the “judicial junta” was an honorable institution so long as it ruled his way.

The long retreat

What are those of us who prefer the early James Kilpatrick to make of his career? First, it is startling to think that even in 1964, a New York State paper would offer a column to a man who had distinguished himself as a segregationist. This is a tribute to Kilpatrick’s ability — he really could write — and a sign of how different the times were. The United States were not quite yet in today’s terrified lock step on race.

Second, even before he sought respectability as a national TV personality, it is curious that he pushed states’ rights as if they had nothing to do with race. Ordinary Americans were never going to care about federal encroachment on state sovereignty unless they were worried about specific policies the feds were trying to undo.

Finally, Kilpatrick, himself, certainly profited from his long retreat. As a domesticated “conservative,” he won fame, wealth, and influence that would have been beyond the reach of a principled “racist.” As Prof. Hustwit notes, Kilpatrick was unquestionably the nimblest of all the segregationists in changing his spots to keep up with the times.

And maybe his views really did change; who is Prof. Hustwit to insist that they did not? But if he did simply bury his convictions, would he have done more good as a provincial race realist than as a national conservative? All people who hedge their opinions in the hope of a larger audience convince themselves that discretion is the price of influence — as they bank their honoraria and swan through the corridors of power. And, like Kilpatrick, they build oases far from the racial chaos they no longer combat with all their strength.

Truth, however, especially the truth about race, needs more than obscure champions. It needs men like Arthur Jensen and Sam Francis. It needs men who are respected and prominent and who, unlike James Watson or James Kilpatrick, refuse to back down.

Kilpatrick unquestionably trimmed to reach prominence. Once he reached the top, would it have simply been impossible for him to speak the truth to the larger audience he obviously craved?

If Kilpatrick really did change, then God rest his erring soul. If he trimmed all the way to the grave, he forsook his obligations to the truth and to his people.