The Mind of the White Man

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, December 2000

From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, Jacques Barzun, HarperCollins, 2000, 877 pp.

From Dawn to Decadence is long, erudite and, despite the attention it has received from the major media, important. In what is probably the last major book in a long and celebrated career, French-born Jacques Barzun writes about the West with an eye to understanding why, as he puts it, “the culture of the last 500 years is ending.”

The official view, of course, is that with ever-expanding rights for everyone, and with a benevolent United States in the lead, we are marching towards a radiant destiny. It is therefore immensely significant that a man of Prof. Barzun’s stature and perspective is prepared to say that our civilization is collapsing. Despite his great learning, Prof. Barzun misses some obvious causes and correlates of decadence, but one can only welcome a major statement from a man who loves the west.

It is important to note at the outset that this is mainly a history book and a diagnosis only in passing. The cultural pulse-taking — though of particular interest here — is sprinkled through perhaps 50 pages out of nearly 900. The rest are a personal and sometimes idiosyncratic account of what the white man has been up to since the Reformation, and Prof. Barzun sees several great themes at work in the last 500 years. From 1500 to 1660 Europe was consumed by the struggle between the Church of Rome and its wayward children. From 1661 until the French Revolution in 1789, Prof. Barzun sees the major questions as the status of the individual and the role of kings and governments. From 1790 until 1920, the west struggled with the question of how to achieve social and economic equality, and since that time it has generally gone into decline.

Prof. Barzun does not stick slavishly to these themes. One of the pleasures of this book is its wide-ranging treatment of people and events, which often come alive charmingly. Each reader will have different favorites, but there is an engaging account of the court of Louis XIV and of the French cultural expedition to Egypt in 1798. We learn how the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra got its name and that the word “opera” is not the plural of “opus.” Prof. Barzun includes an admiring account of the aristocratic form of democracy that kept Venice prosperous for 500 years, and tells the story of the playwright Beaumarchais’ unrecognized efforts in support of the American Revolution.

Jacques Barzun

There are a great many turns and twists in this centuries-long story, most of them well narrated. Even the non-historian, though, can find sour notes. Prof. Barzun takes Tolstoy’s late-in-life saintliness at face value despite his well known debauchery, and seems to think people still take Freud seriously. Even more surprising, he writes that the British gave the Boers “a generous peace” at the conclusion of what was one of the most transparently exploitative wars a European army ever waged.

Decadence

But what about decadence, and why should we care if our culture unravels? Prof. Barzun is bold enough to say it is better than others: “The west offered the world a set of ideas and institutions not found earlier or elsewhere. In the non-western world, elected legislatures are either make-believe institutions or bodies in recurrent disarray.” Western music, “has raised the expressive power of music to heights and depths unattained in other cultures.” He writes that long before we scour the Third-World for scraps to add to the cultural cannon we should rediscover the neglected masterpieces of our own culture. He is disgusted by ritual denunciations of the West and calls the reign of political correctness a modern-day Inquisition.

But to return to decadence, it is important to know how it feels:

It implies in those who live in such a time no loss of energy or talent or moral sense. On the contrary, it is a very active time, full of deep concerns, but peculiarly restless, for it sees no clear lines of advance. The loss it faces is that of Possibility. The forms of art as of life seem exhausted, the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully. Repetition and frustration are the intolerable result. Boredom and fatigue are great historical forces.

One of the institutions that function most painfully is the welfare state; Prof. Barzun puts himself at odds with our time by attacking what many believe to be its greatest achievement. He says any attempt to ensure security for all while promoting the desire for freedom is, “self-contradictory and probably unworkable” and that government hand-outs are “the opposite of charity to the sick and poor.” Writing of the present as if it were already past, he adds, “the task of distributing benefits alone was overwhelming. High taxes were unavoidable, and so was waste . . . There was still poverty, derelicts on the street, unattended illness, and complaints of ‘not enough’ from every welfared group in turn . . . .”

He points out that in the frenzy to distribute wealth the old functions of government like defense and justice become, “a kind of afterthought,” yet no white society dares consider any alternative. Redistribution means that, “legislation filled hundreds of pages, an impenetrable jungle for citizens and officials both” because “the welfare state must pass laws by the bushel.” But most significantly, Prof. Barzun does not even trust the welfare impulse, “[C]ompassion easily becomes a selfish pleasure fostering self-righteousness. It requires a constant supply of the poor and the weak, instead of encouraging the healthful and self-reliant.” All this busy-body uplift has produced a, “ceaseless endeavor to aid and permit [that] was a spectacle unknown to any previous civilization.”

Prof. Barzun has no faith in universal solutions because he understands people are unequal. He writes that Jefferson’s famous declaration about equality was in a denunciation of the abuses of royal power, not in a charter of government. He notes much jabber about the search for excellence, especially in public schools, but finds that, “at the same time the society pounces on any show of superiority as elitism. Observers spoke of the decline of authority, but how could it survive in a company of equals?” He points out that most people are nobodies, not because they are “oppressed” but because of their “modest powers.” He has no time for coddling and excuse-making: “Finding oneself was a misnomer: a self is not found but made.” All this implies that part of our decline is Western man’s determination to deny inherent differences in ability — but Prof. Barzun fails to make this argument.

Still, he piles up signs of decadence with energy and acuity, pointing out that one of its basic symptoms is the disappearance of any sense of forward motion: “This ending [of the culture] is shown by the deadlocks of our time: for and against nationalism, for and against individualism, for and against the high arts, for and against strict morals and religious belief.” He points out that not even science, which in the 19th century seemed infallible, clearly points the way. We are confused by conflicting scientific views on global warming, genetically modified crops, food additives, agent orange, or the costs of illegitimacy. The disappearance of common understanding means the disappearance of common goals:

[M]ost of what government sets out to do for the public good is resisted as soon as proposed. Not two, but three or four groups, organized or impromptu, are ready with contrary reasons as sensible as those behind the project. The upshot is a floating hostility to things as they are.

Prof. Barzun writes that until about 100 years ago, every educated man knew Latin and Greek and that this was a tangible expression of cultural kinship to civilizations thousands of years old. Classical languages have gone the way of universal Bible reading, leaving nothing but television and comic strips as cultural common ground. Likewise, up until the 19th century the purpose of art was moral uplift; Bach, for example, thought of all his compositions as prayer in the form of music. By contrast, today’s art is:

the attack on authority, the ridicule of anything established, the distortion of language and objects, the indifference to clear meaning, the violence to the human form, the return to the primitive elements of sensation . . . .

Prof. Barzun sees similar decline everywhere:

In the 1890s, sports then in their infancy had been praised for developing the high moral outlook called sportsmanship. In less than a hundred years, sports had lost their honor, though not their glamour.

Likewise, until the late 20th century Europeans tried to look their best in public; now, “to appear unkempt, undressed, and for perfection unwashed, is the key signature of the whole age.” The very mechanisms for propagating tradition have decayed:

In our day, celebrations with significant phrases and music have become obsolete; and the words pomp and patriotism invite ridicule. But for centuries such public reminders of community proved indispensable as popular spectacle and conveyor of tradition.

We have witnessed the birth of what is almost a new species:

Modern Man looks forward, a born future-ist, thus reversing the old presumption about ancestral wisdom and the value of prudent conservation. It follows that whatever is old is obsolete, wrong, dull, or all three.

Entertainment becomes the chief goal in life for many people. At the same time, “pluralism” has the practical effect of forbidding judgments of value since no culture or point of view is permitted to be superior to any other. This is reflected in the university, where, “the number of courses . . . kept increasing, in the belief that any human occupation, interest, hobby, or predicament could furnish the substance of an academic course.”

Likewise in the university, Prof. Barzun finds that motive and attitude are often so much more important than facts that if anyone can claim loudly enough that his opponents are tainted he can win the debate by default.

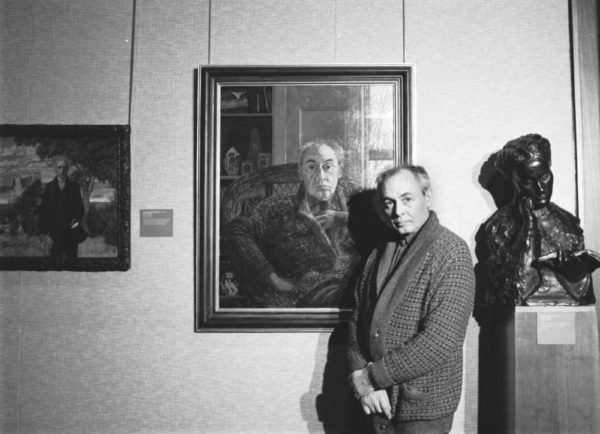

At a more existential level, as Christianity declines, people adopt the view — heretical in any but our own age — that man’s very existence is absurd. It is perhaps in response to this that new cults and religions — a sure sign of decadence — have become so popular. Even among the secular, in the 1970s the Scottish psychologist Ronald D. Laing sowed yet more seeds of distress by arguing that only the insane were really sane.

Ronald Laing beside a portrait of himself at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh February 1985. (Credit ANY Usage: © Scotsman / ZUMA Press)

But perhaps Prof. Barzun’s most concise indictment of our time is to point out that no one today says, as Erasmus and Wordsworth did, “Oh, what a joy to be alive!” Indeed, it is hard to imagine those words on anyone’s lips today.

But what caused our decline? “The blow that hurled the modern world on its course of self-destruction was the Great War of 1914-18;” the West stumbled into a pointless war that killed some 10 million men:

The reckless expenditure of lives was bound to make a postwar world deficient in talents as well as deprived of needful links to the prewar culture. What proved equally devastating in the sequel was the policy of the Allies toward Germany.

Prof. Barzun sees the second war as an almost inevitable consequence of the vengeful peace that ended the first. By then, “western civilization had brought itself into a condition from which full recovery was unlikely.”

Prof. Barzun notes that The Great War was the first total European war. Conscription involved millions of civilians in the first conflict to bring out the full bloodlust of intellectuals, artists, and the clergy. Freud, for example, wrote of “giving all his libido” to Austria-Hungary. Even socialists, who were supposed to defend class rather than nation, happily butchered their fellow proletarians.

Prof. Barzun notes that in 1917 there was a mutiny in the French trenches that was forcibly put down and kept secret. It is yet another sign of our times that in 1998 the French prime minister said the mutineers were worthy of respect, and the press agreed. As another sidelight on the war, Prof. Barzun points out that the use of colonial troops, “marked the entry of Third World settlers into the European nations.”

French soldiers in a trench during World War One.

By unfortunate coincidence, just as the West was tearing itself apart, Communism appeared as an attractive alternative. For many intellectuals, it seemed to offer the promise of a fresh start with clean hands, but it only hastened the decline.

Prof. Barzun sees the war’s effect on art as a harbinger of its deadly effect on everything else. After the carnage, “it was impossible to paint, sculpt, or compose in the old way: equally impossible to start from scratch like a beginner.” Artistic movements began to, “take past and present and make fun of everything in it.”

The Dadaist movement was based on the “the nihilism of the joke” and avant-garde artists praised “the maximum of disorder.” The celebration of Found Art, Junk Art, and Disposable Art, “told the world that art as an institution with a moral or social purpose was dead.” Later, fads of art by children, convicts, the mentally ill and even chimpanzees was part of what Prof. Barzun called “the most enduring idea” of modern times: that there is no such thing as genius and that all people are creative. The result:

Individuals of ordinary talent or glibness were encouraged to become professionals and thereby doomed to disappointment; and too many others, with just enough ability to get by, contributed to the lowering of standards and the surfeit of art.

The 1950s may have seemed a time of cultural coherence, but according to Prof. Barzun the damage had already been done:

Modernism [is] at once the mirror of disintegration and an incitement to extending it. And all this was going on long before the moral, sexual, and political rebellions that shook the western world in the 1960s.

Other Causes

Prof. Barzun proposes no causes for the west’s decadence other than the war. This is particularly surprising because much of his book is about what was once the animating spirit of the west — Christianity — and he fully understands how important the Church has been to Europe. The Reformation, he tells us, was a great psychological blow because: “It posed the issue of diversity of opinion as well as of faith. It fostered new feelings of nationhood . . . It deprived the West of its ancestral sense of unity and common descent.”

Berlin: The sun sets behind the Friedrichswerder Church and the French Cathedral behind lampposts. (Credit Image: © Jens Kalaene / dpa via ZUMA Press)

This was the casen even when Europeans were all still Christians. Prof. Barzun repeatedly underlines how inevitable faith felt to our ancestors:

[I]n earlier times people rarely thought of themselves as ‘having’ or ‘belonging’ to a religion . . . just as today nobody has “a physics;” there is only one and it is automatically taken to be the transcript of reality.

This is in stark contrast to our time in which “people blithely speak of someone’s (or their own) religious preference — as if it were something like a taste in food or sport.” Unquestioned religious unity was an impregnable bulwark against doubt or despair: “When all around take fundamental ideas for granted, these must be the truth. For most minds there is no comfort like it.”

Europe was so much the Church, and the Church Europe that the continent was known as Christendom, and “Christian” and “white man” meant the same thing. In Treasure Island, when Jim comes across a castaway, the first words out of the man’s mouth are “I’m poor Ben Gunn, I am; and I haven’t spoke with a Christian these three years.” Jim himself immediately thinks, “I could now see that he was a white man like myself . . . .”

Christianity made men proof against the nihilism, revolt, cynicism, and rejection of tradition that Prof. Barzun deplores. How can the decline of something so central to cultural and even racial identity not have a devastating effect? Although one could well wonder whether the retreat of the white man’s ancient faith was not, itself, as much consequence as cause of decadence, it is hard to understand how Prof. Barzun managed to overlook the connection.

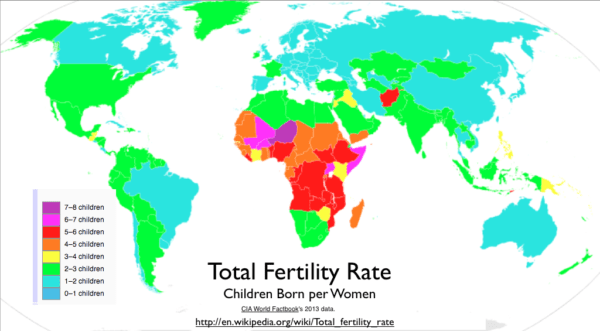

Something else Prof. Barzun has failed to notice is the European’s peculiar inability to reproduce. Every miserable Third-World country has a thriving population, but the wealthiest people in all of history are too cynical and self-absorbed to have children. If anything were a sign of decadence, surely this is.

Not surprising but still disappointing is Prof. Barzun’s obliviousness to race. For example, he laments armed patrols in schools and assaults on teachers, but fails to notice this problem afflicts only certain schools. Perhaps we can expect no better from someone who is also the author of a book called Race: a Study in Superstition (written in 1978 and now mercifully out of print), but he is sniffing around the edges of the problem when he writes:

Look at the phrase ‘our past’ or ‘our culture’ and the reader is entitled to ask ‘Who is we?’ That is for each person to decide. It is a sign of present disarray that nobody can tell which individuals or groups see themselves as part of the evolution described in these pages.

In fact, it is easy to say who Prof. Barzun’s story is about. He need only ask himself how many non-whites have bought his book, much less think of it as a story about “their” people. He also writes that we face, “nothing but constraints at every turn, because the stranger, the machine, the bureaucrat’s rule impose their will. Hence the desire to huddle in small groups whose ways are congenial.” What about large groups whose ways are congenial? Prof. Barzun emits a glimmer of light when he asserts that, “the strongest tendency of the later 20C was Separatism.”

He also notices that the Third-Worlders who have come to the west huddle in their own separate societies and that those who point this out are “racists.” Why can’t he see why this is or where it leads?

He is also on to something when he asks:

‘What Makes a Nation?’ A large part of the answer to that question is: common historical memories. When the nation’s history is poorly taught in schools, ignored by the young, and proudly rejected by qualified elders, awareness of tradition consists only in wanting to destroy it.

This is true and even well put, but who are the people most vociferously calling Columbus a pirate and Washington a slave-driver? If the historical memory of American expansion is a celebration for whites it certainly is not for Indians or Hispanics.

Nicholas Salerno, 18, a fourth-generation Italian, stands in front of the beheaded Christopher Columbus statue in front of Waterbury City Hall on Saturday, July 4, 2020, in Waterbury, Conn. (Credit Image: © TNS via ZUMA Wire)

But at an even deeper level, what can we say about a civilization whose direct heirs seem perfectly prepared to open their homelands to all comers and let themselves be displaced by aliens? This fatal loss of confidence is another unmistakable sign of decay Prof. Barzun would recognize immediately if he were ever to find it in any non-European people. The aliens who are displacing us are eager to overturn our monuments, insult our heroes, rewrite our history, and uproot our culture. They know they are not men of the West and don’t want to be. Their allies among the white self-haters know this, too. It is only the defenders of our civilization who do not understand that it is the work of a specific people. It is one of the profoundest stupidities of our time not to recognize what every non-white knows without reflection: that “the West” is a monument to one race only, and that without that race it cannot survive.