Is American Renaissance on Google’s Blacklist?

Chris Roberts, American Renaissance, June 20, 2020

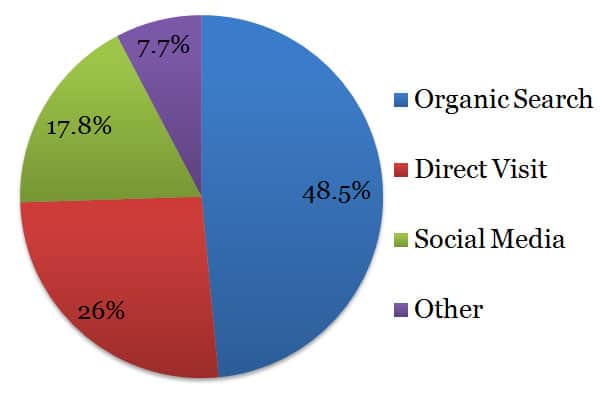

In 2016, half of all visitors to AmRen.com came to us through an “organic search,” meaning that they typed something into Google or another search engine, saw AR in the results, and clicked through to us.

Sources of traffic to AmRen.com in 2016.

Those were numbers to be proud of. Most websites don’t get even half that percentage of visitors through searches. Most websites get a large majority of traffic from “direct visits,” (i.e. just entering the web address). These people know where they want to go. It’s when they don’t know where to go that they do a search and discover something new.

It was a real achievement to get almost half our traffic that way, but not that hard to explain. AmRen covers important topics white people worry about, but may not be able to discuss with neighbors. Some of the most common searches that took people to us were:

- Interracial crime

- Rape by race

- Race and crime

- Interracial murder

- Hispanic crime

- White fertility

Nearly four years have passed since then, and our numbers are very different. In April, only 17.75 percent of our traffic came from searches and 4.23 percent came from social media (17.8 percent four years ago).

It is easy to understand why our traffic from social media is one fourth of what it used to be. In 2016, American Renaissance had a Twitter account with 30,00 followers and Jared Taylor had 40,000. We had many thousands of friends on Facebook. All of those accounts have been banned.

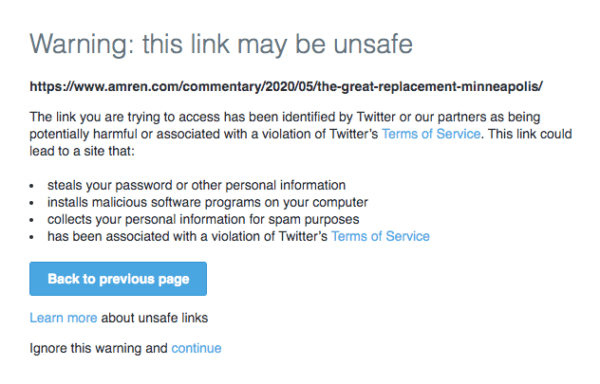

Today, if you include a link to AmRen in a tweet, Twitter issues this warning:

This warning is dishonest. Ours is a news and commentary site, not a content farm run by foreigners or pirates trying to hack you. It is true that when Twitter banned our accounts, it claimed — without explanation — that we had violated its terms of service, but this warning is just a nasty way of saying that Twitter doesn’t like what we say.

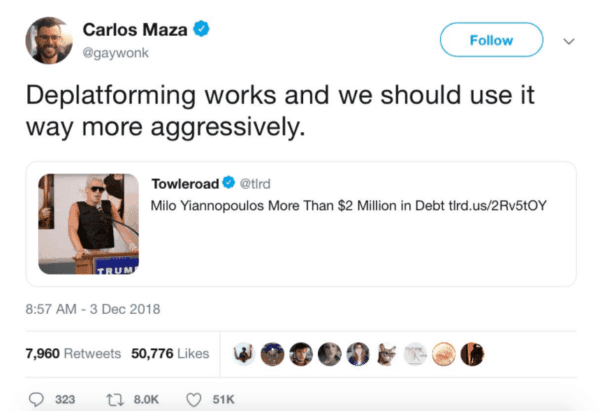

Liberal elites and the establishment media were shocked by the immense popularity of dissident websites. They decided to to stamp out the problem.

As the drop in our traffic from social media shows, censorship works.

It is not as clear why our traffic from searches has fallen. Social media platforms let you know when your account is getting the ax, but Google doesn’t tell you how it may be handling you in search results. In any case, the reason why searches results come up in a particular order isn’t publicly known. There is no smoking gun proving that Google deliberately excludes AmRen from its search results, there are plenty of indications of this.

Up until late 2018, two things on AmRen that received a lot of search engine traffic were our “Color of Crime” report and our article, “New DOJ Statistics on Race and Violent Crime.” One of these two pages came up on the first page of many searches about race and crime. Today, very few searches find them on the first page. It could be because the pages are four years old. Google favors newer results to older ones. However, in 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center announced that it had petitioned Google to ensure that searches about race and crime didn’t lead “fragile minds” to unpleasant truths.

Was our material on crime “de-ranked” because of the SPLC or because it stopped being as fresh as it once was? One can’t be sure, but if you search Google for “color of crime” today, the top result is a 10-year-0ld SPLC article that warns readers about our “blizzard of misleading statistics” and “faulty analysis.”

A good way to test how Google treats AmRen is to search for sentences, sentence fragments, and essay titles that originally appeared on our website. First I search on Google, then on other search engines, and compare the results. I use an incognito windows, signed out of all my email and social media accounts so that my own web history does not distort the results.

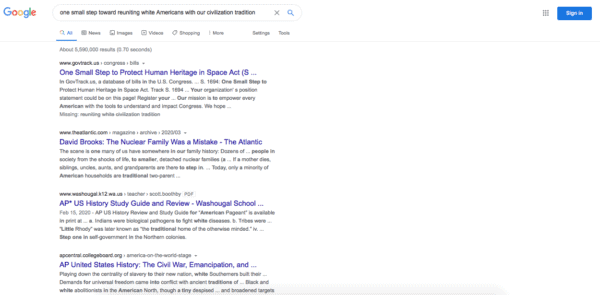

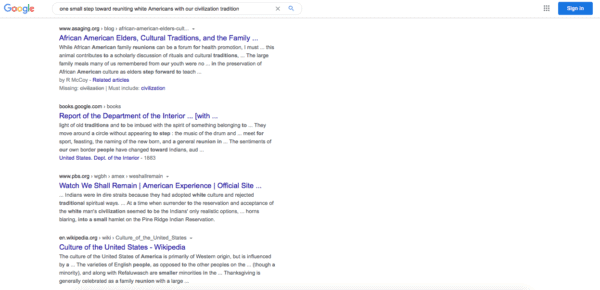

Here is a Google search of one small step toward reuniting white Americans with our civilization tradition, without quotes, which is from Gregory Hood’s essay “Leftists Rage Against Classical Architecture,” published on February 7, 2020.

The result are strange. The first is the text of an unremarkable bill that passed congress a year ago. The fifth is about African-Americans, who aren’t even in the search term. The sixth is a book published in 1883. The eighth and ninth results are both very broad Wikipedia pages.

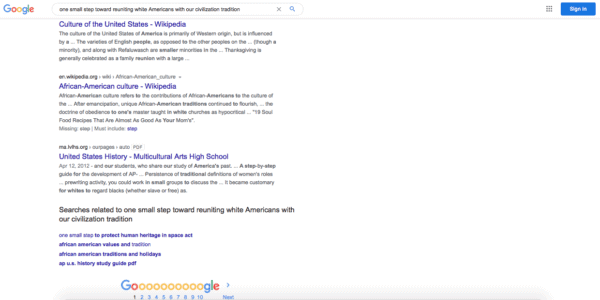

The same search on DuckDuckGo produced very different results. At the top of page one was an article quoting Mr. Hood’s essay, and just below it was the essay itself.

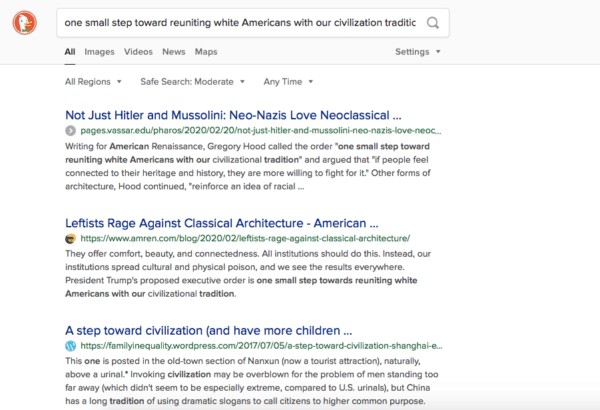

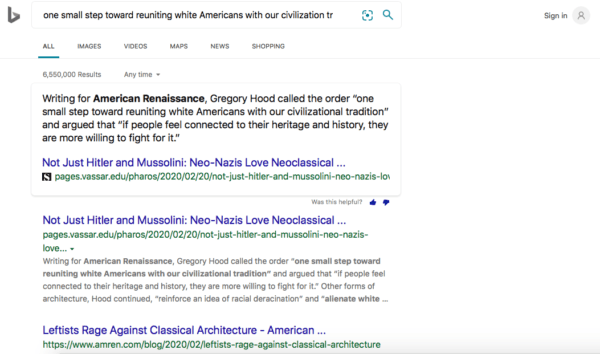

The results on Bing.com were like DuckDuckGo’s:

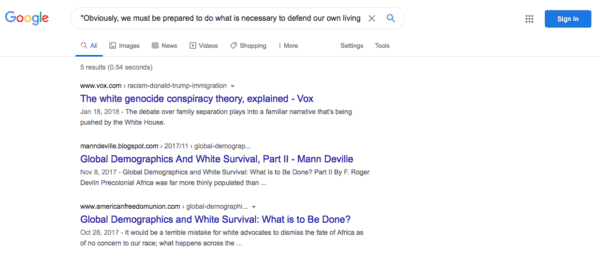

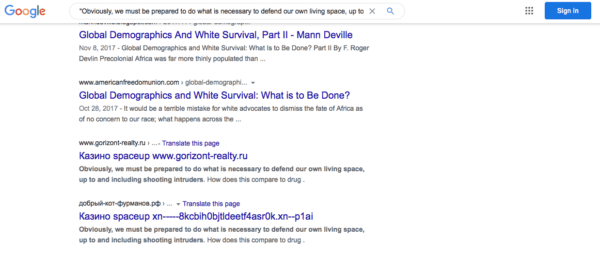

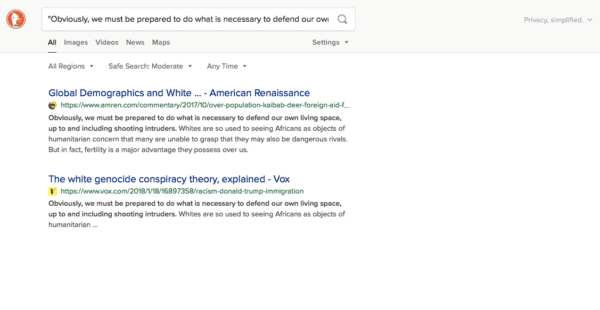

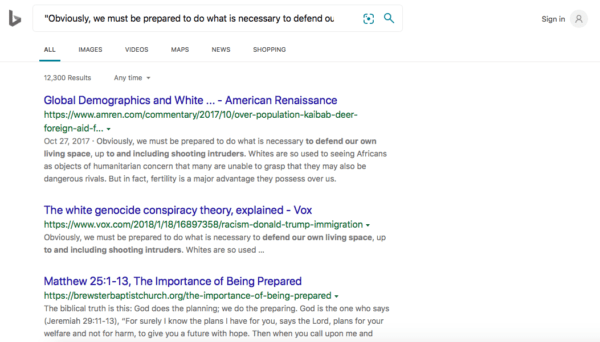

Google results are consistently different from those of other search engines. Here’s the test using the sentence, “Obviously, we must be prepared to do what is necessary to defend our own living space, up to and including shooting intruders,” written by F. Roger Devlin on October 27, 2017. Adding quotation marks in a web search narrows the results to webpages that include the exact words you have typed.

All of Google’s results are websites that quote us, including two foreign websites, but the original AmRen essay isn’t there. DuckDuckGo and Bing have very similar results, with American Renaissance ranking highly on both.

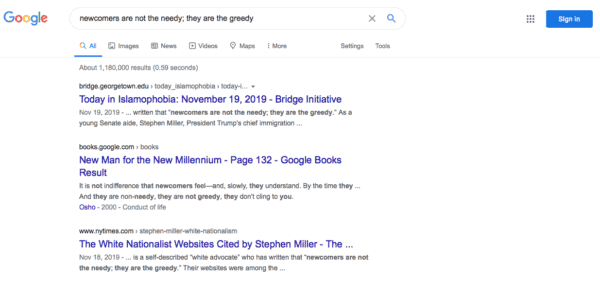

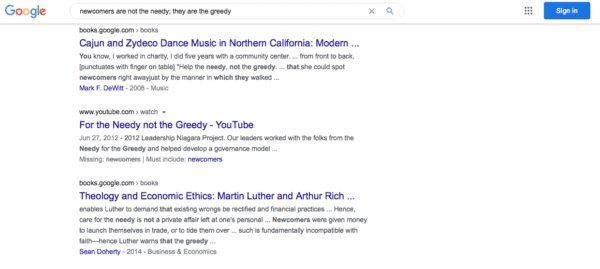

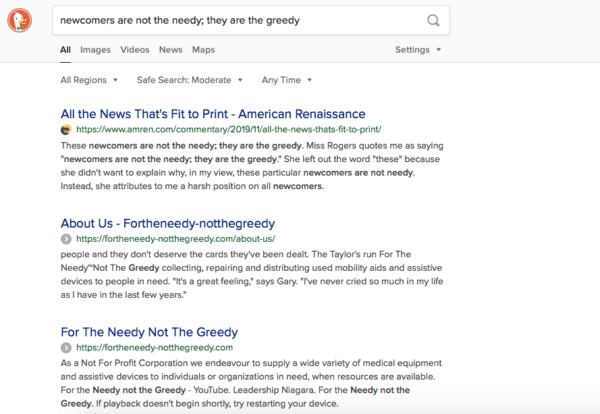

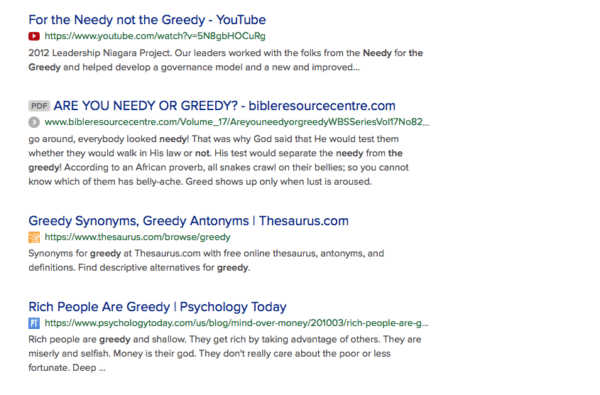

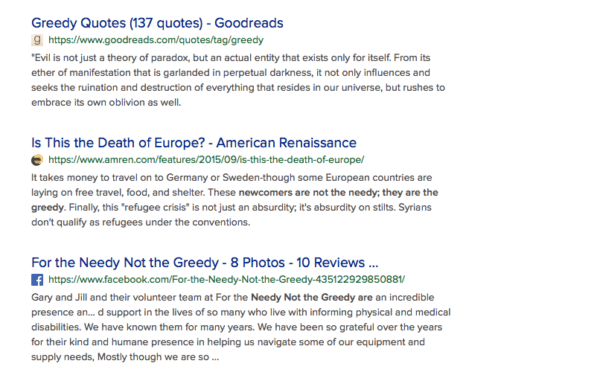

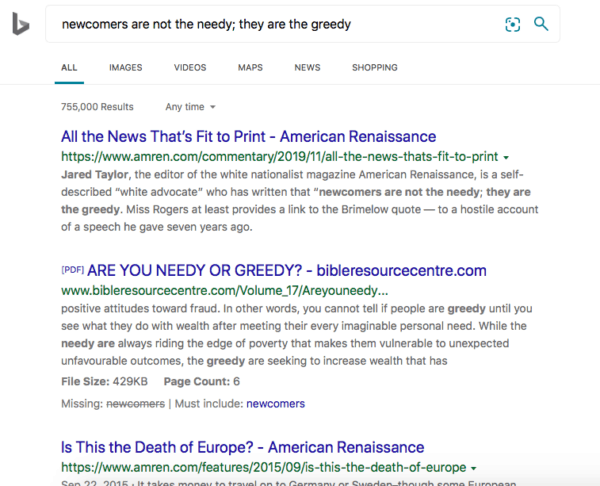

The trend continues with the search results for the phrase These newcomers are not the needy; they are the greedy. without quotes, from Jared Taylor’s essay, “Is This the Death of Europe?” first published on September 22, 2015.

The first and third links are to stories quoting the original AmRen essay, but AmRen is not to be found. The second and fourth links go to books published over a decade ago. Stranger still, the fifth result is a YouTube video from 2012 with under 1,500 views, then another book, and then another news story quoting AmRen. Two video results are returned: one from 2015 with under 1,500 views, and the other is a hit by the pop singer Ariana Grande. Finally, there are two more books; one is over a century old and the other covers events from over a century ago.

Google is supposed to be the most sophisticated search engine, but two of its competitors, DuckDuckGo and Bing did much better:

They don’t give nearly identical results but both do lead to American Renaissance. Google does not — at least not on the first page, where at least 90 percent of searches end. It’s hard to believe that Google is not altering its search algorithm at the expense of American Renaissance.

My default search engine is DuckDuckGo, and I can tell you from years of experience that it isn’t as good as Google. Google is better at understanding what I’m actually looking for and giving me more relevant results. This is so true that at least once a week I scuttle my principles and use Google so I can actually find what I’m looking for. DuckDuckGo gives better results only when I’m looking for something about race.

AmRen.com has not been entirely purged from Google. Sometimes AR appears on the first page (searching “Color of Crime” with or without quotation marks, for example), but The AmRen often does not appear in search results, even when it clearly should. Compared to just a few years ago, there are far more searches without any “hits” for AR.

In November of 2019, the Wall Street Journal published a long article about how Google tunes its search algorithm. Here is a passage from it:

Dan Baxter can remember the exact moment his website, DealCatcher, was caught in a Google algorithm change. It was 6 p.m. on Sunday, Feb. 17. Mr. Baxter, who founded the Wilmington, Del., coupon website 20 years ago, got a call from one of his 12 employees the next morning.

“Have you looked at our traffic?” the worker asked, frantically, Mr. Baxter recalled. It was suddenly down 93% for no apparent reason. That Saturday, DealCatcher saw about 31,000 visitors from Google. Now it was posting about 2,400. It had disappeared almost entirely on Google search.

Mr. Baxter said he didn’t know whom to contact at Google, so he hired a consultant to help him identify what might have happened. The expert reached out directly to a contact at Google but never heard back. Mr. Baxter tried posting to a YouTube forum hosted by a Google “webmaster” to ask if it might have been a technical problem, but the webmaster seemed to shoot down that idea.

One month to the day after his traffic disappeared, it inexplicably came back, and he still doesn’t know why.

“You’re kind of just left in the dark, and that’s the scary part of the whole thing,” said Mr. Baxter.

We are in the dark.