The Great Trek

Dan Roodt, American Renaissance, June 2004

The Dutch ancestors of today’s Afrikaners founded the first permanent white settlement near present-day Cape Town in 1652. In 1795, following the French victory over the Netherlands, the British occupied the Cape Colony to secure the sea lanes around the Cape of Good Hope. The Dutch chafed under what they considered heavy-handed British rule. They resented the abolition of slavery in 1834, and the tendency of the British to treat them as they did the native blacks. These policies were, in the words of one Boer woman, “contrary to the laws of God and the natural distinction of race and religion, so that it was intolerable for any decent Christian to bow down beneath such a yoke, wherefore we rather withdrew in order to preserve our doctrines in purity.”

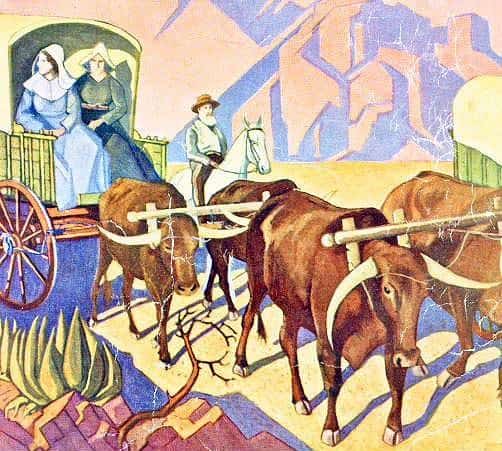

Between 1835 and 1843, some 12,000 Boers, a quarter of those living in the Cape Colony, hitched their oxen to covered wagons, and, with their wives, children, servants, and livestock, moved to the interior in what became known as the Voortrek, or Great Trek, the defining event in Afrikaner nationalism.

The Boers’ intention was not conquest. The lands in and around the Traansvaal, north of the Orange River, had been largely depopulated by tribal warfare. Piet Retief, a Boer leader, had written in a published manifesto that, “We propose . . . to make known to the native tribes our intentions, and our desire to live in peace and friendly intercourse with them.” Nevertheless as the Voortrekkers continued north across the Vaal River they entered lands claimed by the Ndebele, the second most powerful native tribe in southern Africa after the Zulu, and now a substantial portion of the population of Zimbabwe. The Ndebele under Chief Mzilikazi let the first Boer wagons pass unmolested, but began attacking later parties, killing women and children. It was during the fighting against the Ndebele that the Boers perfected their style of warfare.

On October 19, 1836, a party of 40 Boer men, along with their women and children, successfully fought off an attack by thousands of Ndebele warriors at the Battle of Vegkop. They formed their 50 wagons into an outer laager, or ring, lashed them together with chains, and jammed thorn bushes under and between them to prevent attackers from creeping through. Each Boer kept a spare gun or two that his wife had loaded for him. The Boers also cut their bullets so they would split apart in flight and hit several men.

A recreation of the “laager” at the Blood River Memorial.

During the battle, Boer women and children sheltered inside an inner laager of four wagons formed into a square and covered with planks and hides. The Boer men used the laagers only as a final retreat, riding out on horseback with long, large-caliber muskets, called snaphaans, which they loaded and fired from the saddle. They rode well away from the laager and tried to pick off as many warriors as possible before returning.

The Ndebele suffered heavy losses at Vegkop, perhaps 1,000 dead. Their spears could not penetrate the thick canvas covering the wagons, while a blast from a musket loaded with splintering bullets could take down as many as six men. The Boers lost just two men at Vegkop and no women or children. In early 1837, the Boers launched a punitive raid against Chief Mzilikazi, burning his village and killing 400 warriors.

Many Boers were content with the lands they settled in the Traansvaal, but others, including Piet Retief, believed the Afrikaner nation needed access to the sea. This meant crossing into Natal, the land of the powerful Zulus. Retief thought he could negotiate with the Zulu, and on February 6, 1838, he led a party of 66 Boers and 30 black servants under a flag of truce into the camp of Chief Dingaan. After three days of feasting, Dingaan suddenly ordered his fiercest warrior regiment, the Wild Beasts, to “Kill the Wizards!” The massacre of Retief, his men, and their black servants began the Zulu-Boer war.

On February 17, 1838, the Zulu attacked the Boer laagers along the Blaauwkrans River, killing 85 adults and 148 children. It was on this day that Zulus earned a permanent place in the Afrikaner memory by killing infants by dashing their brains out against wagon wheels. Zulu raids continued throughout the year, killings hundreds of Voortrekkers.

By late 1838, the Boers had a new leader, Andries Pretorius (for whom Pretoria is named), who was determined to avenge the murder of Retief and the massacre at Blaauwkrans. On December 15, Pretorius and his force of 470 men spotted an approaching Zulu army of 12,500 men along a tributary of the Buffalo River near present-day Dundee. Pretorius formed his wagons into a D-shaped defensive ring, with two cannon to cover the entrances. Although facing overwhelming odds, his men carried modern Western weapons — flintlock rifles and muskets — whereas the Zulus carried only shields and short stabbing spears known as assegaais, which they seldom threw.

Before the battle, the Boers made a covenant with God: “Here we stand, before the Holy God of heaven and earth, to make to Him a vow that, if He will protect us, and deliver our enemies into our hands, we will observe the day and date each year as a day of thanks, like a Sabbath, and that we will erect a Church in His honor, wherever He may choose and that we will also tell our children to join with us in commemorating this day, also for coming generations. For His name will be glorified by giving Him all the honor and glory of victory.”

The Zulu attacked at dawn on December 16, 1838. The Boers held off the first attack, and the second. Although the Zulu drove right up to the line of wagons, they fought in such tight groups their men stumbled over each other, and withering fire from inside the laager drove them back. After the second repulse, the Zulu seemed hesitant to attack again, but Pretorius lured them into a third assault by sending some men outside the laager as bait. When they attacked again, Pretorius routed the Zulu with cavalry. The fleeing army left behind more than 3,000 dead along the banks of what became known as the Blood River. Astonishingly, not one Boer was killed, and only three were wounded. To the Afrikaners, the victory was indeed divinely ordained.

The Boers kept their vow to God. They built a memorial church in Pietermaritsburg two years later, and celebrated each December 16 as the Day of the Covenant (which the ANC government has officially renamed Reconciliation Day). There are two monuments on the site commemorating the victory. The first is an ox-wagon sculptured out of granite. Nearby is a reconstruction of the laager made of 64 full-size ox-wagon replicas cast in bronze.