Telling It As It Is

Steven Farron, American Renaissance, December 2010

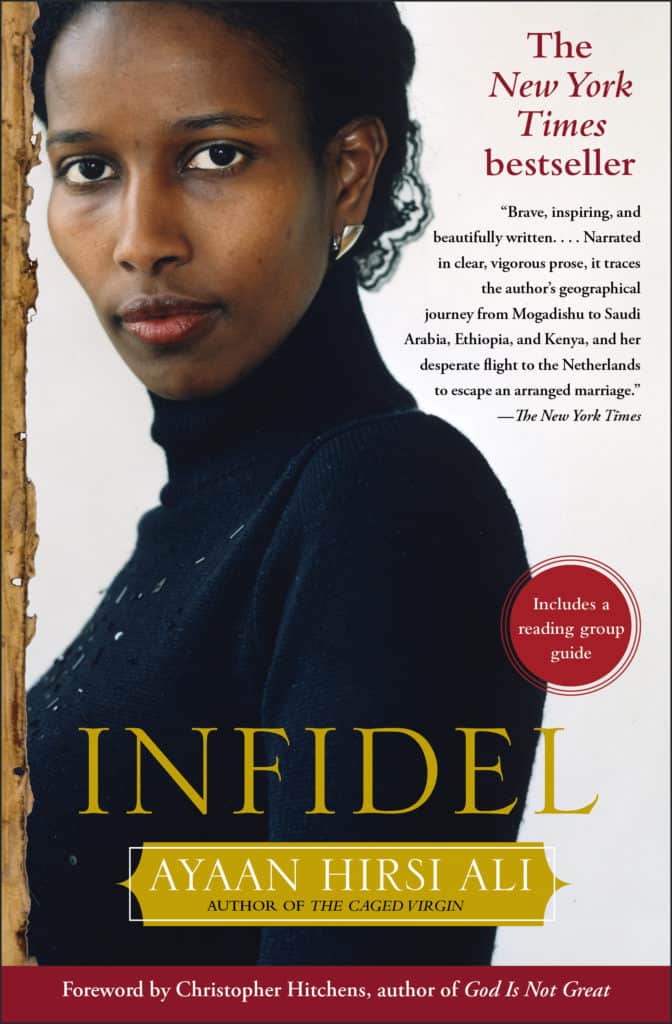

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Infidel: My Life, Pocket Books, 2008, 353 pp.

Most white people either do not know or are too intimidated to say that we have created the most wonderful civilization in the history of the world. So it is fortunate that a black woman has the courage to say it for us.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali was born in Somalia in November 1969. Her father opposed the brutal Marxist dictatorship of Siad Barre. He was imprisoned but escaped and went into exile, where he worked with Somali exiles to try to overthrow Barre’s regime. Miss Ali, her mother, brother, and sister went with him to Saudi Arabia in 1978, Ethiopia in 1979, and Kenya in 1980. In July 1992, at the age of 22, she left her family and went alone to Europe, where she eventually became a Dutch citizen and then a member of the Dutch parliament. She was catapulted into international prominence in 2004 by her movie Submission (Islam means “submission”), which depicted the cruelty Islam inflicts on women and was shown on Dutch television. Shortly afterwards, Theo van Gogh, who produced Submission, was murdered by a Dutch citizen of Moroccan descent, who stabbed into his chest a letter addressed to Miss Ali, which ended with predictions of the destruction of the enemies of Islam: the United States, Europe, and Miss Ali herself.

Four years later, Miss Ali wrote her autobiography, Infidel. In Part I, “My Childhood,” she describes her life before coming to Europe, and Part II, “My Freedom,” begins with her arrival in Europe.

Her entire narrative is fascinating. Of special importance in Part I is her account, from her own experience, of the immense appeal to young Muslims of the more pious, devout, and deeply-felt version of Islam that has been ousting the older, formalistic, ritualistic Islam in which she was reared. She summarizes the difference on pages 87-8 (Pocket Books edition): “A new kind of Islam was on the march. It was much deeper, much clearer and stronger . . . than the old kind of Islam . . . It was not a passive, mostly ignorant, acceptance of the rules . . . It was about studying the Quran . . . getting to the heart of the nature of the Prophet’s message. It was . . . backed massively by Saudi Arabian oil wealth and Iranian martyr propaganda. It was militant, and it was growing. And I was becoming a very small part of it.”

Nevertheless, even before the 1980s, when this new, more potent form of Islam began to become popular, Islam already imposed sex roles that are unparalleled in any other religion. When Miss Ali’s family moved to Ethiopia in 1979, it was the first time she had lived in a non-Muslim country. She recalls, “You could see the difference in the street. Ethiopian women wore skirts only to their knees, and even trousers. They smoked cigarettes and laughed in public and looked men in the face” (p. 56).

In the first sentence of this review, I described Western civilization as “wonderful.” Some readers undoubtedly found that adjective hyperbolic. But that was Miss Ali’s reaction to Western civilization. She was full of wonder. In fact, it was more than wonderful to her; it was awe-inspiring.

In the first sentence of Part II, when she arrives at the Frankfurt airport she says, “I was dazed.” She changed planes for Dusseldorf, where an uncle lived. When she left the airport in Dusseldorf (still on the first page of Part II), “Everything was so clean, it was like a movie. The roads, the pavements, the people — nothing in my life had ever looked like this.” On the next page, she describes with wonder the hotel room in which she stayed. The quilt was “an amazing invention.” The bathroom “was another revelation.” In the next paragraph, she describes what she saw during a walk: “Men and women were sitting together . . . with easy familiarity.” She adds: “Everything was so well kept . . . the street [was] clean. The shopfronts gleamed. I remember thinking, ‘This is amazing’. . . I felt as if I had been thrown into another world, calm and orderly, as in the novels I had read and certain films, but somehow I had never really believed them before.” When she returned to her hotel, a friend of her uncle, a man named Omar, took her to a restaurant. “I . . . realized that all the streets had their names helpfully written on signposts. You didn’t have to stop people constantly and ask them for directions . . . I asked Omar who put them up. He just rolled his eyes and said, ‘This is a civilized country.’ ” With this sentence, she ends her description of her first day in Europe.

Shortly afterwards, she left for the Netherlands, “It was Friday, July 24, 1992, when I stepped on the train . . . I see it as my real birthday; the birth of me as a person.” In the Netherlands, her wonder and awe did not abate at garbage being collected from houses once a week, at a policeman who is “helpful” (her italics); and nearly everything else that we in the West take for granted. When she was told she had been given an A-status as a refugee, which meant that after five years, she could apply for naturalization and could vote, her reaction was, “I didn’t even know they had elections in Holland. What would they vote about? I thought. Everything seemed to work so perfectly” (p. 199).

As time passed, Miss Ali began to realize that something more basic was involved: “I was beginning to see that the Dutch value system was more consistent, more honest, and gave more people more happiness than the one with which we had been brought up” (p. 217).

However, she also knew she was atypical. Most other Somalis in the Netherlands “seemed to spend all their time complaining . . . They weren’t working [because they were being supported by Dutch taxpayers] . . . [They] sat around all night talking about how horrible Holland was” (p. 223). “It irritated me now when Somalis who had lived in Holland for a long time complained that they were offered only lowly jobs. They wanted honorable professions: airline pilot, lawyer. When I pointed out that they had no qualifications for such work, their attitude was that everything was Holland’s fault. The Europeans had colonized Somalia, which was why we had no qualifications. . . [T]he claim was always that they were held back by racism. Everyone seemed to be in a constant simmer about how we were discriminated against because we were black . . . Yasmin . . . and Hasna [two Somali acquaintances] told me that they often didn’t bother paying for buses . . . if the refugee office didn’t give them a ticket they said they were being racist. ‘If you tell a Dutch person it’s racist he will give you whatever you want,’ Hasna told me with satisfaction” (p. 224).

Miss Ali found that Somalis were typical of Third-World immigrants in the Netherlands. She became friendly with a Moroccan woman named Naima. Naima’s husband, also a Moroccan, beat her frequently. “Naima complained constantly, but it was about the Dutch . . . She never complained about the violence and humiliation she suffered at home, only about Dutch racism” (p. 232).

Islam

Miss Ali was reared as a Muslim. When she was an adolescent, she became fervidly devout, but her fervor had subsided by the time she arrived in the Netherlands. She soon stopped wearing a headscarf. Then she studied Darwin, Freud, and Spinoza. She found Western thought vastly superior to anything she had been taught before: “The more I read Western books, the more I wanted to read them . . . I was enamored with the idea that you could think precisely and question everything” (p. 248). Nevertheless, until 2001 when she was 31, she continued to consider herself a Muslim.

Then came the September 11 attack on the Twin Towers. Her immediate reaction was to think, “Oh Allah, please let it not be Muslims who did this.” That night, Dutch television showed Muslim children in the Netherlands rejoicing at the attack. Miss Ali was working at a think-tank of the Labor Party, which had a plurality in the Dutch parliament. The next morning, “I found myself walking to the office with Ruud Koole, the chairman of the Labor Party . . . He said, ‘It’s so weird, isn’t it, all these people saying that this has to do with Islam?’ I couldn’t help myself . . . I blurted out, ‘But it is about Islam [her italics] . . . This is Islam.’ Ruud said . . . ‘[T]hese people . . . are a lunatic fringe. We have extremist Christians, too . . . Most Muslims do not believe these things. To say so is to disparage a faith . . . which is civilized and peaceful.’ I walked into my office thinking, ‘I have to wake these people up.’. . . It was not a lunatic fringe who felt this way about America and the West. I knew that the vast majority of Muslims would see the attacks as justified . . . This was not just Islam, this was the core of Islam” (pp. 268-9).

Miss Ali proceeded to dissect the “infuriatingly stupid” reasons proposed for the attack: poverty, Western colonialism, American support for Israel, arguing that none of these explanations can withstand even a moment’s analysis (pp. 270-72). What Osama Bin Laden and those like him believe comes straight from the Quran and the hadith. “Every devout Muslim who aspired to practice genuine Islam . . . even if they [sic] did not actively support the attacks, they must at least have approved of them.” Moreover, on the basis of what the Quran itself narrates, “[T]he Prophet Muhammad . . . [was] a cruel man who demanded absolute power and who stunted creativity” (p. 303).

In the last three pages, Miss Ali concludes: “I moved from the world of faith to the world of reason . . . Having made that journey. I know that one of those worlds is simply better than the other . . . When people say that the values of Islam are compassion, tolerance and freedom, I look at reality, at real cultures and governments, and I see that it simply isn’t so. People in the West swallow this sort of thing . . . for fear of being called racist.”

Race

Miss Ali discusses at considerable length the causes of the extremely high rates of poverty, unemployment, and crime among Muslims in the Netherlands, and the backwardness of Muslim countries. However, she never mentions the possibility that racial differences could be a cause. Obviously, she simply assumes they are not, and nothing could more clearly show how thoroughly Westernized her thinking has become. The only people in her book who do not think race is significant are white Europeans. Everywhere she lived before coming to Europe, physical differences were regarded as crucially important. References to race pop up constantly in her account of her experiences as a child and adolescent, but they are offered only as casual details that provide a full portrayal of her youth. Consequently, few readers probably notice that they form a significant pattern. They do.

In 1978, when Miss Ali was eight, her family moved from Somalia to Saudi Arabia. There, they lived first in Mecca and then in Riyadh. At her school in Mecca, “All the girls . . . called Haweya [her sister] and I [sic] Abid, which meant slaves. Being called a slave — the racial prejudice that term conveyed — was a big part of what I hated in Saudi Arabia” (p. 42). (“Abid” is the plural of the Arabic word “Abd,” which means both slave and black person.) At her school in Riyadh, “The teacher was an Egyptian woman, and she used to beat me. I was sure she picked on me because I was the only black child. When she hit me with a ruler she called me Aswad Abda, black slave-girl. I hated Saudi Arabia” (p. 49).

However, the racial situation reversed when her family moved to Kenya, in 1980. Somalis’ skin is somewhat lighter than Kenyans’ skin, and their facial features are nearly Caucasian. She recalls that “Kenyans . . . looked different from us. To my mother, they were barely human . . . She called them abid, which means slave . . . [M]y grandmother said Kenyans stank. Throughout the ten years they lived in Kenya, the two of them treated Kenyans almost exactly as the Saudis had behaved to us” (p. 61).

Miss Ali attended Muslim Girls’ Secondary School in Nairobi, where many of the children were from India and Pakistan: “The Untouchable girls, both Indian and Pakistani, were darker-skinned. The others wouldn’t play with them” (p. 68). She also recalls that “on the school playground . . . [t]he Yemenis, Somalis, Indians, and Pakistanis played with each other and interacted, but in the hierarchy of Muslim Girls’ Secondary School, the Kenyans were the lowest” (p. 68). It is extremely unusual for natives of a country to be socially inferior to immigrants. Yet, in her school in Nairobi all immigrant groups were higher in the social hierarchy than the Kenyans. Miss Ali seems to have thought that the reason was so obvious she did not have to state it: the Kenyans were the darkest and the only ones with Negroid features. When Miss Ali was 16, a teacher at her school, Sister Aziza, a Kenyan of Arab extraction, converted her from ritualistic, superficial Islam to the new, all-encompassing Islam that was spreading rapidly. Miss Ali recalls, “Sister Aziza was young and beautiful — light-skinned and fine-nosed” (p. 80).

After Miss Ali had left for Europe, her sister had an abortion after becoming pregnant by a man from Trinidad who worked in Nairobi. Miss Ali explains what her mother would have thought of this man: “Flat-nosed, round-faced, kinky-haired. My mother would have seen such a man as subhuman, like the Kenyans” (page 226).

I will add to Miss Ali’s references the promise that the Saudi Arabian cleric Sheikh Muhammad al-Munajid made on Saudi TV on July 25, 2009, that the 72 virgins with which every pious Muslim man will be rewarded in Paradise will be “beautiful white young women . . . They are like precious gems . . . in their whiteness.”

In fact, with only one exception, everywhere in the world, for as far back as records go, lighter skin color has been regarded as both more aesthetically appealing and as an indication of superiority. Color and Race, edited by John Hope Franklin (pages 91-5, 119-20, and 129-85) documents belief in the superiority of whiteness among Chinese, Japanese, Mongolians, Black Africans, American Indians, and Asian Indians; Bernard Lewis does the same for the Islamic world in Race and Color in Islam. Ironically, the only people who do not think whiteness indicates superiority are Europeans and people of European origin of just the past few decades; even though they are the whitest of all races and the people whose achievements could entitle them to feel superior.

Miss Ali’s book brings to mind an incident that was reported in the South African newspaper Business Day on April 8, 1993 (“Race Row Flares over World Cup Encounter”). In a World Cup qualifying game, the Egyptians defeated the Zimbabweans 2-1, but the result was annulled because a crowd in Cairo stoned Zimbabwe’s players and officials. The Egyptian soccer magazine Al-Ahlawiya wrote about Zimbabweans, “They haven’t forgotten that they are slaves, and naturally there is a great difference between masters and slaves. They look at everything that is white with a sore eye, because their hearts are filled with hatred.” In response, a Zimbabwean wrote in the Herald, the largest circulation newspaper in Zimbabwe, “I didn’t know the Egyptians were white, maybe because they have achieved nothing close to what a real white man has achieved.”

We have reached the pathetic situation in which we must rely on black people, like Ayaan Ali and the above-quoted Zimbabwean, to tell us what we have achieved.