Beaten to Death at McDonald’s

David Paulin, American Thinker, August 21, 2014

To the four clean-cut college freshman out on a double date, it had seemed like a typical McDonald’s: spanking clean, well-lighted, and safe. It was in a good neighborhood too, right next to Texas A&M University in College Station–a campus known for its friendly atmosphere and official down-home greeting: “howdy.”

Shortly after 2 A.M. that Sunday, they pulled into the parking lot of so-called “University McDonald’s” and beheld a scene unlike anything portrayed in all those wholesome McDonald’s television commercials. Before them, hundreds of young black males were loitering about, some without shirts.

Other local residents–the more cynical and world-weary, both whites and most blacks–would have taken one look at the crowd and driven off, dismissing many of the young and posturing black males as thugs. But not them: innocent white kids from the suburbs. They presumed this was post-racial America–and that they were in an easy-going college town.

Twenty minutes later, two of them were dead.

Incredibly, the race of the assailants was scrubbed from local news coverage; and utterly missing from tersely written wire-service stories about a Brazos County jury’s whopping $27 million negligence verdict on July 30 against “University McDonald’s”–an outlet owned by the Oak Brook, Illinois-based fast-food giant. What the media considered unmentionable nevertheless loomed over a riveting seven-day trial, which came amid the growing phenomenon of black-on-white violence–unprovoked attacks on whites and black mob violence like the so-called “knock-out game.”

Chris Hamilton, lead lawyer of the small Dallas firm that humbled the corporate giant, was asked, during a phone interview, how many reporters had even bothered to inquire about the race of the assailants during the many interviews he gave.

“You’re the only one,” he replied.

Race, of course, was irrelevant to the high-stakes negligence trial that revolved around McDonald’s lack of on-site security and corporate responsibility. Yet shortly before the trial, Hamilton hinted at the issue of race–suggesting that two very different worlds were colliding at University McDonald’s during its after-midnight hours–a mix that was potentially volatile. The upcoming trial, he told a local television reporter, was not only about seeking justice for his clients but about the public’s need “to know what’s really going on at McDonald’s: what the risks are; what the dangers are of sending your kids there, particularly after midnight.”

His extensive pretrial investigation–numerous depositions, pathology reports, and an in-depth analysis of police records–told a story that was heartbreaking and infuriating, and that until the trial had remained largely out of pubic view as the case was handled by College Station Police, Brazos County District Attorney Jarvis Parsons, and an asleep-at-the-wheel news media.

Apart from legal arguments over alleged corporate negligence, the high-profile trial offered a shocking view of how a thuggish black subculture flourished at University McDonald’s. The blame could be laid squarely upon McDonald’s black managers, and on the failure of higher-ups in McDonald’s to ensure patrons, both black and white, were safe during late-night hours–an increasingly lucrative market for the fast-food giant.

Beaten to Death

For the two young couples, the evening had started at a country-western concert at “Hurricane Harry’s” in College Station’s entertainment district; and afterward, just after 2 a.m. on Sunday, February 18, 2012–a quick trip to nearby “University McDonald’s” as it’s widely known.

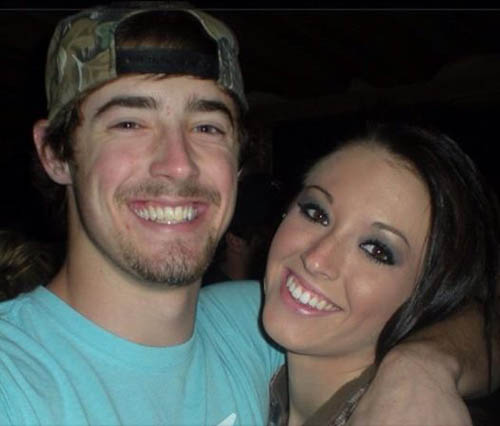

Parking his Toyota 4Runner, Denton James Ward, age 18, stepped down from the big SUV with Tanner Giesen, then 19 years old. The two friends from Flower Mound, an affluent Dallas suburb, headed to the McDonald’s bathroom; Ward wore his cowboy hat. The girls, Lauren Bailey Crisp and Samantha Bean, both 19, took the SUV to the drive-through.

Both inside and out, University McDonald’s was bustling. But it definitely wasn’t the usual daytime crowd –– clean-cut and mostly white “Aggies” as A&M’s students are known. Instead, up to 400 black males were loitering about the parking lot, a police officer later estimated. Inside, it was mostly a black crowd too: a large number of black males were loitering about, many without food. Some were shirtless.

This was the usual after-midnight crowd on Saturdays and Sundays at the 24-hour McDonald’s. And unbeknownst to the two couples–and many in College Station–this McDonald’s was a major late-night trouble spot.

Police were constantly responding to late-night fights, assaults, and disturbances among huge crowds that were mostly black–a problem one top police official called a “drain on resources.” Most of the reported incidents, some 200 in the three years preceding Ward and Crisp’s deaths, involved black-on-black violence by gang bangers and, according to one police officer, members of black college fraternities. One police report described an unidentified man’s head getting bashed against a curb. White patrons appeared to be especially susceptible and at risk–and when they were attacked, the blows were particularly vicious. The hours of 2-to-3 A.M. on Saturdays and Sundays were especially volatile, with at least a dozen fights and assaults reported during those hours in the year preceding these deaths.

For Ward and Giesen, the trouble started seconds after exiting McDonald’s front door. “You’re in the wrong neck of the woods, cowboys,” Giesen recalled a young black male saying.

Unwittingly, they’d blundered into a highly-charged situation. Shortly before they’d arrived, two black males had gotten into a loud argument inside the restaurant. A gun was brandished. But manager Lindsey Ives, a black woman, didn’t call the police. She told the men to take their dispute outside.

In an instant, a bloodthirsty mob was upon them.

A fist slammed into Giesen’s face. Ward tried to break-up the altercation, according to trial testimony. Instead, he suffered a brutal mob stomping lasting several minutes. Some 20 young black males closed in–mercilessly kicking and punching his head and body and even jumping on him after he fell to the ground, witnesses said. Giesen was knocked unconscious.

An athletic young man–5-foot-6 and 163 pounds–Ward had a handsome face framed by a mop of rusty brown hair. But after the beating, one witness–a retired U.S. Marine and one of a few white customers–said Ward’s face was “really messed up”; was “broken” and “mushy” and “just did not look natural.”

Bean and Crisp, both 19, rounded the corner of the drive-through to see the mob stomping. The horrified and frightened young women jumped out of the SUV screaming for it to stop. Crisp, Ward’s girlfriend, even rushed into the melee, according to trial testimony. Blood poured from Ward’s face. Some nearby good-Samaritans, including a few black females, helped the frantic teens lift their dates into the 4Runner’s back seat; Ward was unable to speak or walk. Danisha Stern, a trial witness, then told them to “get out of there . . . it’s not safe.”

Immediately, the terrified girls took that advice–rather than waiting for police. Bean, Giesen’s date, took the wheel with Crisp occupying the front passenger seat. Speeding away, Bean made a frantic across-town dash for an emergency room. She worried somebody from the McDonald’s mob might follow and run her off the road.

Ward was drifting in and out of consciousness. Blood was everywhere. Fearing he was slipping away, Crisp frantically climbed into the back seat, kneeling on the floorboard to do what she could–pushing him back into his seat when he slumped forward. They had been dating three months. The girls were “freaking out,” Giesen recalled. “I remember lots of screaming and yelling going on.”

Then–about 10 minutes after speeding away from University McDonald’s–Bean ran a red light. The 4Runner was hit broadside by a Chevy Silverado pick-up, and then spun violently and crashed into a light pole. Ward and Crisp were pronounced dead at the scene; Bean and the Silverado’s five occupants were uninjured. Police initially thought Ward and Crisp had died in the crash, and they had considered charging Bean. But pathologists at the negligence trial, both for the plaintiffs and McDonald’s, agreed Ward was beaten to death–the fatal kicks and punches delivered to the lower back of his head and chin.

The mob at McDonald’s grew into a frenzy after the couples fled. A police officer arriving at the scene, five minutes later, grabbed his AR-15 assault rifle when he stepped out of his patrol car, fearing he was amid a full-blown riot. It was, he recalled, like “scenes that we have seen multiple times at that McDonald’s.”

Crisp, a dark-haired beauty from Dripping Springs, a suburb of Austin, wanted to be a nurse. She was a biology major at Blinn College as was Bean, a resident of College Station. Ward, also a student at the junior college, was set to transfer to Texas A&M the next year to study industrial engineering. He had an all-American background in high school: letters in football and baseball; Little League umpire; and a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. He and Crisp were from large families.

Giesen was briefly treated at an emergency room; his abdomen bore a boot print. He now suffers bouts of amnesia due to brain trauma.

In College Station, nobody dared to ask if a “hate crime” had possibly occurred. But Stern, the black good-Samaritan, testified that the black mob had piled on Ward in part because he was white; or as she explained: “He was trying to save his friend or stop the attacks…targeted at his friend. And he was a white male so I guess any–anything that was–anybody that was not helping the fight, like, adding to the injury or whatever, was seen as an opponent or something, you know.”

Police made only one arrest, charging Marcus Jamal Jones–known to friends as “Plucky”–in the mob attack. Without outdoor security cameras and uncooperative witnesses, it was no doubt hard to make a case. Last March, Plucky pleaded guilty to misdemeanor assault and served a 90-day jail sentence.

Minutes after the mob attack, the 6-foot-2 Plucky entered the McDonald’s without a shirt. “We was fight’en,” he was heard to say. Earlier in the evening, he’d said he was looking for a fight, witnesses reported.

Playing the race card

It was Plucky who introduced the word “nigg-r” into the case. After his arrest, he told police that seconds before Ward and Giesen were attacked, somebody had said “nigg-r.” But he admitted he didn’t know who’d uttered the epithet, or even if the person was black or white. During the trial, he changed his story, claiming Giesen had uttered the epithet. But Giesen denied using a racial slur and identified Plucky as the person who’d remarked, “You’re in the wrong neck of the woods, cowboys.”

Interestingly, Plucky got a job with a McDonald’s supplier, Mid-South Baking Company in Byran, Texas, three months before the trial–and before his epiphany that Giesen was the person who’d said “nigg-r.”

Why was University McDonald’s so popular among black gang bangers and black fraternity members? Carlos Butler, the outlet’s black general manager, could take credit for that. An aspiring hip-hop artist, he hosted large hip-hop concerts attracting some 1,500 people–and after those events many of the black hip-hoppers headed to University McDonald’s.

Interestingly, Butler told a police detective he always had “a lot of security” at his hip-hop events.

Yet at University McDonald’s, Butler had no off-duty police officer providing security–even on nights that the hip-hop and gangsta crowd showed up in large numbers.

Cost for an off-duty cop–a mere $100. Police had told Butler such a late-night security measure, in use at other nearby 24-hour outlets, could stop trouble before it started.

The all-white jury–eight women and four men–took only four hours to render their $27 million judgment: $16 million for Ward’s parents; $11 million for Crisp’s.

According to a recent article in The Eagle, a daily paper in College Station, the problems at University McDonald’s persist. Lawyers for McDonald’s have vowed to appeal. They are sticking to their argument that poor choices made by the two couples–namely their underage drinking and Bean’s reckless driving–were responsible for Ward and Bean’s deaths. McDonald’s definitely took the negligence case seriously, though. During opening arguments, it had 12 lawyers at the defense table. Hamilton handled the contingency-fee case with two associates–nearly 40 percent of the legal talent in a firm of eight lawyers. “They tried to bury us in paperwork and money,” he remarked.

Parents and relatives of Ward and Crisp attended the trial, but on Hamilton’s advice sat outside the courtroom except when testifying about how the deaths of their children had affected them. They are not giving interviews. Hamilton, however, said they felt vindicated that the jury had rejected the blame-the-victim strategy of McDonald’s lawyers. Marshall Rosenberg, lead lawyer for McDonald’s, did not respond to an e-mail seeking comment.

The media’s handling of this case was no surprise: political correctness rules in America’s newsrooms. But imagine a hypothetical crime: two clean-cut black couples go into University McDonald’s during the daytime–and are viciously attacked by a mob of whites. An international media circus undoubtedly would erupt. Big-time journalists from all over the world would descend on College Station to deal with the deplorable state of America’s race relations caused by bigoted whites. President Obama would weigh in with a few comments about America’s racial sins; and Attorney General Eric Holder–just as with the Ferguson disturbances–would travel to College Station, where Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton would be leading protest marches.

But the narrative they’re promoting is false.

It obscures where most of the hate is coming from. Crime statistics have long reveled the real problem: high levels of black-on-black violence, followed by black-on-white violence, and mob attacks–and the latter two phenomena have been on the increase at an alarming rate, underscoring deep pathologies in a growing black-thug subculture–even as liberals in the mainstream media and Washington are unwilling to acknowledge this fact.

The late Ray Kroc, the legendary McDonald’s entrepreneur and CEO, must be rolling over in his grave over what’s happening. The hood has expanded its turf in the America he loved–and now even hangs out under the Golden Arches.