Fade to Brown

Stephen Webster, American Renaissance, April 2003

The signing of the 1965 Immigration Act.

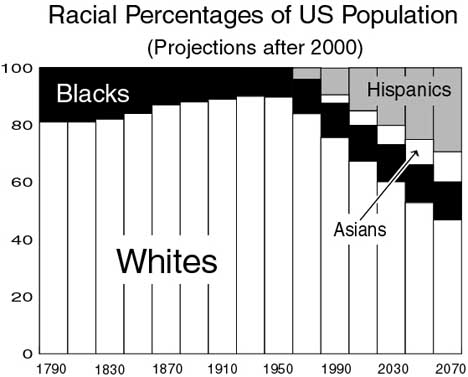

Of all the unfortunate legislation to emerge from the so-called Civil Rights Era, none has been more harmful than the 1965 Immigration Act (technically, the amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, or the Hart-Celler Act of 1965). In 1960, whites were approximately 90 percent of a population of 178.5 million. By 2000, they were only 69.1 percent of a population of 281.4 million, and if current immigration trends continue, by 2050 or 2060 they will be a minority of a population of 430 million or more. This will be a decline from overwhelming majority to minority in little more than a lifetime. Thanks to the 1965 Act, which brought about a radical departure from traditional patterns of immigration, white children born today will enter middle age as minorities in their own country.

Early Immigration Policies

The post-1965 changes would shock the architects of America’s earlier immigration policies, which were intended to keep America white and culturally cohesive. The young nation’s very first naturalization law, passed in 1790, required that new citizens be “free white persons.” Most immigrants coming to the United States during the republic’s first 60 years were Northwestern European Protestants, mainly from Britain and Germany. They differed very little — ethnically or religiously — from the pioneers who settled colonial America, and they helped establish traditional American culture.

The first substantial change to that pattern was the result of the Irish potato famine of 1845 and political turmoil in Europe around 1848, which fueled a rapid influx of Irish and continental Catholics. The first immigration reform movement, the so-called Know-Nothings or members of the secret Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, was established in 1849 in response to these new immigrants. The Know-Nothings — who got their nickname because they were pledged to say they “knew nothing” if asked about the order by outsiders — were cultural nationalists who thought Catholicism was incompatible with America’s liberal, democratic political values. They wanted to bar the foreign-born from voting or holding public office, and called for a 21-year residency requirement for citizenship and the establishment of mandatory public schools to mold newcomers into proper Americans.

The order soon gave rise to a mass movement known as the American Party, which won hundreds of local, state and federal elections. The Congress that met in 1855 had no fewer than 43 avowed Know-Nothing members, and the American Party even ran former president Millard Fillmore in a bid for the White House in 1856, in which he won 21.5 percent of the popular vote. Its growing success was stopped short when the party split over slavery. As the Civil War approached, many northern Know-Nothings joined the new Republican Party, while Southerners defected to the Democrats. The movement faded, but its insistence that immigrants should assimilate became part of the American identity and is its lasting legacy.

Millard Fillmore

Some states took immigration policy into their own hands. In 1855, California levied a fine of $55 per person on Chinese immigrants. Three years later, when it was clear the fine had not stopped the flow, the state passed an outright ban on all people of “Mongolian” descent, except in cases of shipwreck or accident. Survivors were expelled as soon as they recovered. The city of San Francisco passed its own laws, taxing Chinese laundries and door-to-door vegetable peddlers. Perhaps most imaginative was a “queue” ordinance, which required a mandatory haircut for anyone convicted of a crime. This was aimed at Chinese, for whom it was a great disgrace to lose the pigtail.

From 1854 to 1874, Chinese could not testify against whites in California courts. The legislature declared that Chinese “have never adapted themselves to our habits, modes of dress, or our educational system . . . Impregnable to all the influences of our Anglo-Saxon life, they remain the same stolid Asiatics that have floated on the rivers and slaved in the fields of China for thirty centuries of time.”

In 1875 the US Supreme Court declared immigration a federal, not a state responsibility, but the US government picked up where California and other states left off. Beginning in 1882, it passed a series of laws barring Asians. The first Chinese exclusion act, in force for 10 years, was renewed in 1892 and 1902. In 1904 Congress made the ban permanent, and it was in effect until 1943, when China was our ally in the war against Japan, and a total ban seemed unfriendly.

Japanese and Koreans tried to immigrate later than the Chinese, but got the same treatment. The Japanese and Korean Exclusion League, founded in 1905 in San Francisco, whipped up so much anti-Asian sentiment that Teddy Roosevelt persuaded the Japanese government in 1907 to withhold passports from anyone who wanted to emigrate to America — the so-called Gentleman’s Agreement. The Immigration Act of 1917 created an “Asiatic Barred Zone” that virtually eliminated all Asian immigration, and also required literacy tests for European immigrants.

During this period, there was another round of European immigration, known as the Great Wave. Unlike earlier European arrivals, Great Wave immigrants were mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe, and differed far more significantly — culturally, religiously, linguistically and ethnically — from native stock than had the Irish and German Catholic immigrants of the 1840s. It was a far larger wave, which peaked in 1907 with 1.3 million foreigners, but continued to roll along until the First World War. In the decade between 1900 and 1910, nearly nine million immigrants arrived, a number not exceeded until the 1990s.

Immigration resumed after the war. More than 800,000 came in 1920 alone, and the Commissioner of Immigration predicted the number would soon rise to two million a year. Worried that this flood threatened the Anglo-Saxon majority, Congress acted in 1921 to protect the demographic balance.

Albert Johnson, chairman of the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization and who gave his name to the new law, put it this way: “The United States of America, a nation great in all things, is ours today. To whom will it belong tomorrow? . . . The United States is our land. If it was not the land of our fathers, at least it may be, and it should be, the land of our children. We intend to maintain it so. The day of unalloyed welcome to all people, the day of indiscriminate acceptance of all races, has definitely ended.”

The Johnson Quota Act of 1921 was the first to put numerical restrictions on immigrants. It set an annual ceiling of 357,000 Eastern Hemisphere immigrants — this meant Europeans — but there was no limit on Western Hemisphere immigration because aside from a few white Canadians, no one was coming from the Americas. The law also established an annual quota for all national groups of three percent of its representation in the 1910 census — a provision clearly intended to keep the ethnic balance exactly as it was. The 1921 Quota Act was provisional, and was replaced in 1924 by the Johnson-Reid Immigration Act, which further reduced immigration. It cut Eastern Hemisphere arrivals to just over 160,000, and lowered the quota for different nationalities to two percent of that nationality’s representation in the earlier census of 1890.

By using population figures from before the massive post-1900 immigration surge, the drafters of the act tried to undo some of the demographic change wrought by the Great Wave. The quotas ensured that 70 percent of all immigrants would be from Great Britain and Germany — the countries that provided nearly all of the founding stock — and Ireland. Business leaders had opposed the quotas, and wanted to import crowds of cheap foreign workers, but when Calvin Coolidge signed the 1924 act, he noted that maintaining a common national culture was more important then whatever economic benefits more immigrants might bring.

This meant an unmistakable preference for the old Americans over Italians, Czechs, Poles, etc. and even at the time there was much complaining about “discrimination.” Colorado Congressman William N. Vaile replied to these charges during the debate on the 1924 Quota Act: “That people from Southern and Eastern Europe did not begin to come in large numbers until after 1890 certainly proves that those who came before them had built up a country desirable enough to attract these latecomers. Shall the countries which furnished these earlier arrivals be discriminated against for the very reason, forsooth, that they are represented here by from 2 to 10 generations of American citizens, whereas the others are represented by people who have not been here long enough to become citizens? If there is a charge of ‘discrimination,’ the charge necessarily involves the idea that the proposed quota varies from some standard which is supposed to be not ‘discriminatory.’ What is that standard?”

Already we see the signs of eventual capitulation. Congressman Vaile was suggesting that the quotas were not discriminatory, or if they were, it was because they violated an impossible standard. Vaile would have served subsequent generations better if he had been more straightforward: Certainly the quotas were discriminatory, but Old Americans had every right to discriminate in favor of themselves, and in favor of cultural and ethnic continuity. To concede that discrimination was wrong, but that national quotas were somehow not discriminatory was to concede a moral position that could only lead to defeat.

Already in 1927, immigrants from Eastern Europe succeeded in getting Congress to change the quota baseline from the 1890 to the 1920 census, thereby opening up more slots for themselves. In exchange, Congress slightly reduced the annual Eastern Hemisphere quota to 154,227 — a figure that remained in effect until 1965. There was still no quota on immigration from the Americas, because no quota was needed.

The next major change in immigration law was the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (the McCarran-Walter Act). This act eliminated the ban on Asians — each Asian country was allotted a token 100 immigrant visas — and established a preference system within the national origin quotas favoring immigrants with special skills or family ties to citizens. The act did not alter either the basic quota system or the annual ceiling on immigration from the Eastern Hemisphere.

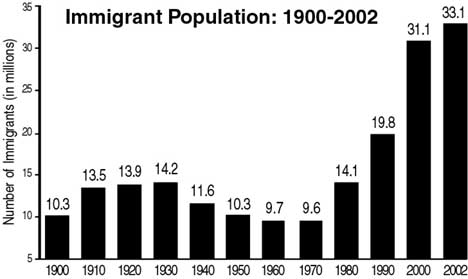

The immigration reforms of the 1920s were a great success. They ended Great Wave immigration (from 1930 to 1970, annual net immigration averaged 185,000), and gave non-traditional immigrants time to assimilate. America in 1960 was still the white nation its founders intended, but by then, the racial and cultural consensus that produced the quota system had begun to break down.

Quota Opponents

There were opponents to McCarran-Walter, including President Harry Truman. The law had to be passed over his veto, and he complained about “the cruelty of carrying over into this year of 1952 the isolationist limitations of our 1924 law.” “In no other realm of our national life,” he added “are we so hampered and stultified by the dead hand of the past, as we are in this field of immigration.” Truman was hardly a multi-racialist. He was a firm segregationist (despite integrating the army), and once wrote, “I am strongly of the opinion Negroes ought to be in Africa, yellow men in Asia and white men in Europe and America.” His real objection to national quotas was that they gave the Soviet Union a reason to tell Third World people America was “racist.” Despite the Cold War, the quota system was overwhelmingly popular. The House of Representatives voted 278-113 to override the veto, and the Senate voted 57-26.

Note decline during the First World War, and the success of the restrictions of the 1920s. The spike in 1991-2 is due to IRCA amnesties.

Truman was not alone, however, in worrying that immigration quotas were a liability in the Cold War. Novelist Pat Frank, in Alas, Babylon!, a story of nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the United States published in 1959, has the lead character, a Southern liberal, lament that “nativists” were “losing” Asia. This belief is one of the main reasons McCarran-Walter set up token quotas for Asians. President Dwight Eisenhower wanted to double immigration at the very least, and to bring in thousands of East European and Asian refugees from Communism, but Congress stood firm.

Popular opposition to quotas came mainly from people who thought the system discriminated against their group. After the Second World War, quotas from Britain and Germany largely went unfilled, and there was no provision to let other countries take their slots. In 1965, 250,000 Italians competed for 5,666 quota slots. Italian ethnic lobbyists and Southern and Eastern Europeans desperately wanted to change the quotas, but did not have enough political power.

Most ethnics worked only to get more of their own people into the country, but Jews consistently lobbied for more immigration from everywhere. American Jews have always favored liberal immigration policies, in the belief that Jews are more secure in a culturally diverse country without a strong racial, cultural, or religious identity. Throughout the 19th century, American Jews fought all exclusionary immigration laws, even those aimed at Asians. They were particularly opposed to the quota acts, which they saw as an anti-Semitic reaction to the recent arrival of large numbers of Jewish immigrants.

Groups like the American Jewish Committee funded and directed much of the anti-restrictionist activity. During the 1930s when Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler were barred from entry, Jews were almost the only segment of American society pressing for more immigration, and Jewish organizations poured enormous amounts of money and effort into helping pass the 1965 Immigration Act.

However, if there is one man who can take the most credit for the 1965 act, it is John F. Kennedy. Kennedy seems to have inherited the resentment his father Joseph felt as an outsider in Boston’s WASP aristocracy. He voted against the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, and supported various refugee acts throughout the 1950s. In 1958 he wrote a book, A Nation of Immigrants, which attacked the quota system as illogical and without purpose, and the book served as Kennedy’s blueprint for immigration reform after he became president in 1960.

In the summer of 1963, Kennedy sent Congress a proposal calling for the elimination of the national origins quota system. He wanted immigrants admitted on the basis of family reunification and needed skills, without regard to national origin. After his assassination in November, his brother Robert took up the cause of immigration reform, calling it JFK’s legacy. In the forward to a revised edition of A Nation of Immigrants, issued in 1964 to gain support for the new law, he wrote, “I know of no cause which President Kennedy championed more warmly than the improvement of our immigration policies.” Sold as a memorial to JFK, there was very little opposition to what became known as the Immigration Act of 1965.

Immigration as a Civil Right

The historical context of the bill was very important. Writer Lawrence Auster describes the Immigration Act of 1965 as a “civil rights bill applied to the world at large,” because although it was billed as a tribute to a fallen president, it was very much a part of the revolution in race relations of the 1960s. Congress passed it at the same time as the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and its purpose was to end the discrimination of national origins quotas. Indeed, its supporters often invoked the domestic “civil rights” bills in calling for support.

As Rep. Phillip Burton of California put it: “Just as we sought to eliminate discrimination in our land through the Civil Rights Act, today we seek by phasing out the national origins quota system to eliminate discrimination in immigration to this nation composed of the descendants of immigrants.” Another Democratic congressman, Robert Sweeney of Ohio, said: “I would consider the amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act to be as important as the landmark legislation of this Congress relating to the Civil Rights Act. The central purpose of the administration’s immigration bill is to once again undo discrimination and to revise the standards by which we choose potential Americans in order to be fairer to them and which will certainly be more beneficial to us.” Immigration reform was a moral crusade, and like so many other moral crusades, it was sold on the pretense that it would actually be “more beneficial to us.”

Supporters of the 1965 Immigration Act made another questionable argument: that it was really only a symbolic gesture that would not produce much real change. At the signing ceremony, President Johnson declared, “This bill we sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not restructure the shape of our daily lives.”

Senator Edward Kennedy, who guided the bill through Congress, reassured Americans that “our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. Under the proposed bill, the present level of immigration remains substantially the same . . . Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset . . . Contrary to the charges in some quarters, [the bill] will not inundate America with immigrants from any one country or area, or the most populated and deprived nations of Africa and Asia . . . In the final analysis, the ethnic pattern of immigration under the proposed measure is not expected to change as sharply as the critics seem to think.”

Illinois Democratic Congressman Sidney Yates added, “I am aware that this bill is more concerned with the equality of immigrants than with their numbers. It is obvious in any event that the great days of immigration have long since run their course.”

Rhode Island Democratic Senator Claiborne Pell agreed: “Contrary to the opinions of some of the misinformed, this legislation does not open the floodgates.”

Some saw writing on the wall. Barry Goldwater’s running mate in the 1964 presidential campaign, Rep. William Miller of New York, warned “We estimate that if the President gets his way, and the current immigration laws are repealed, the number of immigrants next year will increase threefold and in subsequent years will increase even more . . .

During debate on the act, Florida Democratic Senator Spessard Holland told his colleagues, “What I object to is imposing no limitation insofar as areas of the earth are concerned, but saying that we are throwing the doors open and equally inviting people from the Orient, from the islands of the Pacific, from the subcontinent of Asia, from the Near East, from all of Africa, all of Europe, and all of the Western Hemisphere on exactly the same basis. I am inviting attention to the fact that this is a complete and radical departure from what have always heretofore been regarded as sound principles of immigration.”

As “conservatives” almost always do, opponents of the 1965 act could not bring themselves to defend their positions honestly and clearly. Senator Holland evoked “sound principles of immigration” but did not explain why they were sound. There is no record in the congressional debate of anyone pointing out that European civilization can be carried forward only by Europeans, that Third-World immigrants bring the Third-World with them, and that whites have every right to keep their country white. These arguments would not necessarily have prevailed, but they would have been straightforward, coherent statements of racial common sense rather than wooly appeals to “what have always heretofore been regarded as sound principles.”

On Oct. 3, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the act at a ceremony at the base of the Statue of Liberty. What were its provisions? Most significantly, it abolished the national origins quota system and gave all foreigners an equal chance. It slightly increased the quota for the Eastern Hemisphere — which now meant not just Europe but Asia and Africa as well — to 170,000, and established a ceiling of 120,000 for Western Hemisphere immigrants.

Just as significant was an important shift in preferences. Before 1965, skilled professionals were at the top of the list, and family unification got little emphasis. The new law reversed this, meaning that the Third-Worlders who could now come were not being chosen for what they could do but because they were related to someone who was already here.

Until 1965, people admitted to the country legally had no automatic right to bring their families; skilled professionals came before wives and children. The new law gave the top preference to unmarried adult children of US citizens but the very next preference category was spouses, minor children and unmarried adult children of immigrants. This was a huge change. Under the old law, only citizens had the right to sponsor immigrants. Now, as soon as he got here, any newcomer could send for his family. This is what produced the chain migration that has emptied entire Mexican villages.

The allocation of hemispheric quotas was another dangerous precedent. No country in the Eastern Hemisphere could send more than 20,000 people a year, but the 120,000 Western Hemisphere quota had no per-country limits at all. This set the stage for a single country — Mexico — to dominate immigration.

And, indeed, the 1965 Immigration Act and its sequelae have restructured the shape of our daily lives. Our cities are being flooded with a million immigrants annually, and the ethnic mix of our country has been upset. The year after the 1965 act, 323,040 immigrants arrived. During the 1970s, the numbers averaged 450,000 a year. In the 1980s the average yearly intake rose to 740,000, and by the 1990s, the figures reached 900,000. These were only the legal immigrants, and we now have an estimated seven to thirteen million illegals living among us — the equivalent of eight to fourteen years worth of legal immigration. Some 350,000 to 500,000 break into the country every year.

If illegals are included, between 1970 and 1980, the number of foreigners living in the US rose by 47 percent (4.5 million). Between 1980 and 1990, the number rose by another 40 percent (5.7 million), and during the 1990s, increased by a staggering 57 percent (11.3 million, the largest single-decade increase ever). This meant that in 2002, 33.1 million immigrants were living in America — 11.5 percent of the total population. Immigration drives US population growth. Since 1965, immigration and the children of immigrants have accounted for 70 percent of the increase, giving the United States population growth rates like those of Third-World countries.

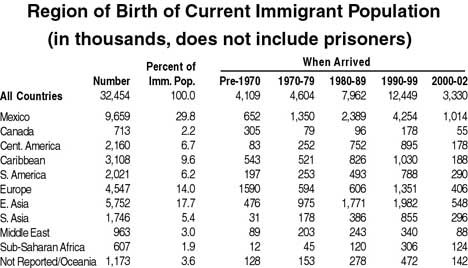

Nearly 90 percent of recent immigrants are non-whites, and most are from Latin America or Asia. Pace Senator Kennedy, we are indeed being inundated with immigrants from one country — Mexico. There are now no fewer than 20.6 million Mexicans in this country, of whom 9.7 million are first-generation immigrants. Mexico alone accounts for 29.8 percent of all current legal immigrants and the majority of illegals.

Whites have been largely pushed out of the immigrant stream. Seventy percent of foreign-born residents come from Latin America, the Caribbean, and East Asia. Of the top ten countries sending immigrants to the US, only one — Canada at number nine — has a majority white population, and probably for not much longer. America’s traditional sources of immigrants are far down the list. Germany ranks 11th and Britain is 12th. Ireland is not even in the top 25. Whites are a majority in only six of the top 25 source countries, and by no means all of the immigrants they send are white.

Bad as it was, the 1965 act cannot take all the blame for the rising tide of color. That law could theoretically have held immigration at 300,000 every year. Since then, Congress has yanked up the quotas while doing little to screen immigrants for useful skills. In 2000, for example, the country accepted 849,807 immigrants, nearly three times as many as envisaged in 1965. Of that number, 41 percent were immediate family members of US citizens and 28 percent were relatives of non-citizens, meaning that no fewer than 69 percent were let in because of family ties. Another eight percent were refugees — this is how we get Somalis, Nicaraguans, etc. — 13 percent received employment preferences, six percent came on “diversity” visas chosen by lottery for people who don’t have family connections, and four percent got into the country one way or another and had their status adjusted to get permanent residency.

Of course, one of the most breathtakingly stupid things Congress did — and this includes the 1965 act — was the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). This was a law passed in 1986 that granted amnesty to illegals who had been in the country since before 1982 and had kept their noses reasonably clean. This was supposed to be a once-and-for-all, never-again amnesty to be combined with tough policies to keep out any more illegals. The Border Patrol was supposed to be beefed up, and there was to be fierce punishment for employers who hired any more illegals that came in. In the end, no fewer than 2.6 million law-breakers got amnesty, very few of them white, and the illegals just kept on coming. “Employer sanctions” were a joke, and the IRS soon gave up anything but token enforcement. It was back to business as usual: Anyone who could make it across the border had little to fear from la Migra.

The surge in immigration initiated by the 1965 act shows no sign of slowing. Neither the foundering economy nor the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks have discouraged newcomers: More than 3.3 million legal and illegal immigrants have arrived since 2000. Immigration boosters say this is a natural phenomenon over which we have no control, a byproduct of the global economy. Of course, it is no more uncontrollable than the Great Wave of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which was stopped by the quota acts of the 1920s.

Now that immigration is destroying the unity and cultural coherence of the country, it has become fashionable to describe vice as a virtue, to claim that ethnic enclaves, schools full of children who speak no English, increasing racial conflict, voodoo cults, bilingual ballots, Mexican irredentism, interpreters in hospitals and courtrooms, and countless “discrimination” cases are all evidence of wonderful enrichment and “diversity.” No one can point to just how diversity is actually benefiting the country but everyone is convinced it is a great thing.

Jews, in particular, continue to think they are better off in a rag-bag country with no majority. As Charles Silberman has written, “American Jews are committed to cultural tolerance because of their belief — one firmly rooted in history — that Jews are safe only in a society acceptant of a wide range of attitudes and behaviors, as well as a diversity of religious and ethnic groups.” The Hebrew Immigration Aid Society (HAIS) has traditionally worked to increase Jewish immigration to the United States, but now that fewer Jews are coming, it has opened an office in Nairobi, of all places — explicitly to encourage non-Jewish immigration. As HAIS president Leonard Glickman recently explained to the Jewish paper Forward, “The more diverse American society is the safer [Jews] are.” Earl Raab, president of Brandeis University, has argued that only when whites are reduced to a minority will the United States no longer be capable of establishing an anti-Semitic, Nazi-like regime.

Recently a few Jews have begun to wonder if massive Third-World immigration is not quite so good for them after all. Stephen Steinlight, a former executive of the American Jewish Committee wrote a paper in 2001 in which he argued that Hispanics and Asians are not sufficiently sensitive to Jewish interests, and that Muslim immigrants are a clear threat. Some individual Jews have spoken out strongly against Third-World immigration, but Jewish organizations overwhelmingly favor it. Gentile whites generally resist “diversity” arguments, and large majorities consistently tell pollsters they want fewer immigrants.

The arguments of the supporters of the quota system — that it was necessary to maintain cultural cohesion — are now more obviously true than ever. In the 1920s and as late as the 1950s, whites still had enough unspoken racial consciousness to pass laws in their own interests. They failed, however, to put the case in clear, racial terms, and as racial consciousness diminished, whites in the 1960s were even less capable of making racial arguments, and found themselves disarmed in the face of appeals to “equality” and “non-discrimination.”

Our nation achieved character and greatness precisely because of discrimination. Our ancestors understood that people and races are not interchangeable, and that failure to discriminate would produce a warring mix of incompetents and unassimilables. If we are not to lose our country, it is up to us once again to make racial principles an explicit part of the national debate. Unless “conservatism” is rescued from the capitulationist spirit of compromise piled on top of compromise, our grandchildren will not have a country worth conserving. If our generation fails to save the country it will be too late.