Integration Has Failed (Part I)

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, February 2008

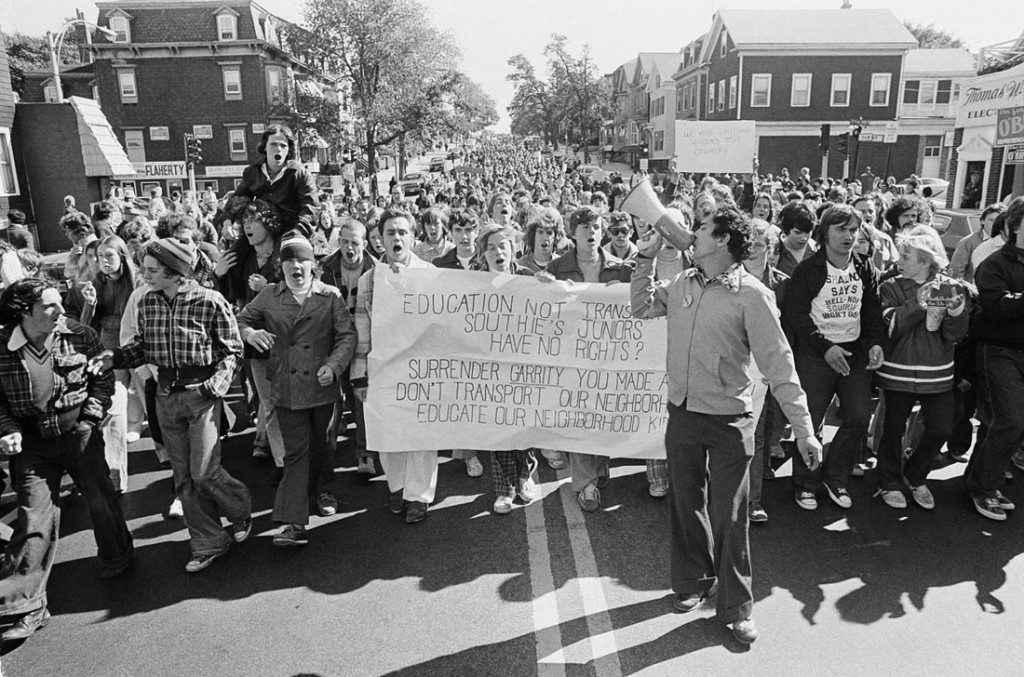

Some 5,000 march through South Boston to protest school busing in 1974.

Meredith Brace of San Diego, California, believes in integration. She lived in a largely white area, but the neighborhood school, Harding Elementary, was 90 percent Hispanic. She was convinced whites should go to Harding rather than escape to a white school. Even before her son was old enough to enroll, she joined the PTA, raised money for Harding, and went door-to-door to promote it to white neighbors. She became president of the PTA and held neighborhood meetings to encourage whites to attend. After her son started going, she set up after-school art and theater classes to bring whites and Hispanics together. They failed because not enough people signed up.

She kept her son at Harding for three years before finally giving up. “[W]e have nothing in common [with Hispanics],” she said. “Every time my husband and I would go over for an event, my husband would feel like it was his first time. We haven’t made any friends.” Her son made no friends either. “He hasn’t been invited to a birthday party,” she explained. “There is absolutely no after-school interaction. For his birthday, he invited four of his classmates. Only one came.”

Mrs. Brace finally joined the neighbors she had tried so hard to convince to go to Harding. Saying she could no longer treat her son like a guinea pig, she transferred him to Hope Elementary School, which was still 73 percent white. As one white parent explained, “[I]f half of [the neighborhood] is going in that direction, maybe we can carpool.”

It is lunch time at the Westerly Hills Elementary School in Charlotte, North Carolina. Black and white children sit next to each other in what seems to be complete disregard for race. The school appears to have passed what educators call the “lunchroom litmus test,” of whether children make friends across racial lines. But the test is rigged. The children at Westerly Hills have assigned seats; that is the only way to get blacks and whites to eat together.

Columbia, Maryland, was founded in 1967 as a planned community of up-scale homes, where blacks and whites would live together in harmony. It considered itself a model for the country, and in the 1970s prospective home buyers were proudly told that Columbia’s first baby was born to a mixed-race couple. The town attracted people with an unusual commitment to integration and racial equality, but by the 1990s, blacks and whites had drifted apart. Residents noted that self-segregation was most pronounced among children and teenagers.

Integration is clearly not progressing as Americans in the 1960s expected it to. Two full generations have been reared with the ideals of racial equality, and yet racial separation is almost as pervasive today as it was 40 or more years ago.

Integration was the cornerstone of America’s great campaign for racial equality. It was the goal of sit-ins, Freedom Riders, demonstrations, and civil disobedience. It was sought with equal enthusiasm by blacks and white liberals alike. For those who were crafting a new racial future, integration was to be the first step towards realizing America’s full democratic potential. It was the decisive first step towards a future in which race would cease to matter.

Today, almost no one talks about integration. Partly, that is because the civil rights struggle completely destroyed segregation, removing all legal barriers to integration. Every law Martin Luther King ever hoped for has been passed, and governments at all levels devote enormous efforts to rooting out any remaining vestiges of racial discrimination.

A more significant reason why few people talk about integration is that there is not much of it to talk about. Voluntary, widespread racial mixing is rare. In law and in theory, race not only does not matter, it is forbidden that it matter. In practice, race is a prominent and persistent social barrier. There has been no official declaration of defeat, but the failure of integration underlines just how far from realization is the dream that inspired the racial activists of the middle of the last century. Some Americans live in broadly diverse settings, but far more do not.

Integration was of enormous symbolic importance for two reasons. First, segregation was the clearest possible expression of racial inequality. Many Americans came to believe it was unconscionable to shut out anyone because of something so meaningless as race. But abolishing legal segregation was only the first step. True integration was the key to unblocking the entire racial log-jam, to making the races equal in every respect.

Half a century after the confident predictions of the 1960s, it is high time to review the record. If integration has not been made to work — much less unblock the log-jam — what will? If integration was expected to come smoothly, yet fails to materialize generation after generation, what does that say about the assumptions of the civil rights movement? If race still matters after 50 years of campaigning, when will it cease to matter?

Theory of Integration

The theoretical basis for integration was established in An American Dilemma, written in 1944 by the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal. With the possible exception of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, no other book has even approached its influence on American thinking about race. An American Dilemma went through 25 printings — an astonishing record for a dense, thousand-page work of sociology — before it went into a second, “twentieth anniversary” edition in 1962. It set contours for the debate about race that have lasted virtually unchanged until our own day.

One of the book’s key passages explains why integration is the essential first step to solving the “American dilemma:”

“White prejudice and discrimination keep the Negro low in standards of living, health, education, manners and morals. This, in its turn, gives support to white prejudice. White prejudice and Negro standards thus mutually ‘cause’ each other.”

This was the heart of the problem: Whites despised blacks and kept them in an artificially inferior position. Whites then pointed to this apparent inferiority as justification for their own prejudices, which gave rise to more acts of oppression that degraded blacks.

Myrdal believed that the great obstacle to progress was white prejudice. If white attitudes could be reformed, oppression would ease, the status of blacks would rise, white attitudes would improve further, and blacks would find yet more opportunities for success. Myrdal was convinced that if the vicious cycle could be turned into a virtuous cycle it would unlock the nation’s true potential: “[T]he Negro problem is not only America’s greatest failure but also America’s incomparably great opportunity for the future.” If the United States could turn this failure into a triumph it would fulfill its promise as a light unto all nations.

Myrdal’s supporters thought change would come quickly. Myrdal’s assistant, Arnold Rose, added a chapter called “Postscript Twenty Years Later” to the 1962 edition. After a triumphant description of the progress made since the book’s original appearance in 1944, he predicted that all legal discrimination would be abolished within ten years (it actually took only three) and that in 30 years — by 1992 — residual private friction between blacks and whites would be “on the minor order of Catholic-Protestant prejudice.”

Rose was wrong, but his view was typical. When the Supreme Court outlawed school segregation in its seminal 1954 decision of Brown v. Board of Education, Thurgood Marshall, who argued the case for the black plaintiffs, believed it would take perhaps five years before full school integration was achieved nationwide. So did Kenneth Clark, the black educator whose work on the psychological effects of segregation on black children helped persuade the Supreme Court to order school desegregation. “I confidently expected the segregation problem would be solved by 1960,” he later wrote.

Integration was the key to overcoming white prejudices because as they mixed with blacks, whites would discover a common humanity that transcended race. Integration would still have to be handled properly, however. Whites would be best exposed to blacks under supervised conditions that made it clear how irrational racial prejudice really was.

Discussions about how blacks and whites were to be brought together came to be known as “contact theory,” and its most prominent spokesman was Gordon Allport. His 1953 book, The Nature of Prejudice, was frequently read in conjunction with An American Dilemma. “Prejudice,” he wrote, “. . . may be reduced by equal status contact between majority and minority groups in the pursuit of common goals. The effect is greatly enhanced if this contact is sanctioned by institutional supports . . . ”

Schools were the perfect setting for controlled contact. White children, whose prejudices had not yet hardened, would mix with black children under conditions of equality and institutional support. Many others agreed that school integration was the essential first step. James S. Liebman of the Columbia University School of Law wrote that integrated education was the best way to reform “the malignant hearts and minds of racist white citizens.” In order to protect children from the “tyranny” of their parents he recommended that they be required to attend “schools that are not entirely controlled by parents,” where they could be exposed to “a broader range of . . . value options than their parents could hope to provide.”

Liberal intellectuals thought their judgment was better than that of ordinary Americans, and urged government to enforce enlightened views. Jennifer Hochschild of Princeton wrote that school integration was so important that it justified limiting the will of the people. Democracy would have to “give way to liberalism,” and Americans “must permit elites to make their choices for them.” She even said parents should be banned from sending children to private schools, because they would escape the benefits of integration.

By the 1950s, liberals therefore had a clear strategy: Integration would cure Americans of prejudice. White adults might not integrate willingly, but white children who went to school with blacks would grow up with enlightened views. The racial problem would finally be solved.

In the Brown decision, the Supreme Court was willing to set aside certain legal considerations to achieve this high goal. Chief Justice Earl Warren’s ruling was light on Constitutional reasoning but cited An American Dilemma, noting the psychological damage segregation was said to do to blacks. As Paul Craig Roberts and Lawrence Stratton point out in their 1995 book, The New Color Line, the Brown ruling was not based on law but on the urgings of sociologists and the desire to do what was right. “In the eyes of the Justices and their peers, desegregation had become the hallmark of moral society,” they wrote. “Legal reasoning played no role” in the decision. Even the New York Times recognized the sentimental rather than legal nature of the ruling in its headline of May 18, 1954: “A Sociological Decision: Court Founded Its Segregation Ruling On Hearts and Minds Rather Than Laws.”

Initially, desegregation meant only that blacks could no longer be kept out of white schools — it did not require deliberate mixing by race — and Brown applied only to the legally segregated schools in the South. Most Southern school districts duly dismantled strict segregation but made no effort at integration. A small number of ambitious black parents transferred their children to white schools but whites did not transfer to black schools.

The era of passive desegregation ended in 1968, when the Supreme Court ruled in Green v. New Kent County that Southern schools had to do more than open their doors to a few blacks. Campuses were to be deliberately integrated through race-based student assignment, and the 1971 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg decision sanctioned busing as the preferred means of doing so. It was not until the 1973 decision of Keyes v. Denver, however, that the court ordered race-based assignment of students in school districts outside the South that had never practiced legal segregation, and where segregated school attendance merely reflected housing patterns. Gordon Allport’s “contact theory” was being implemented nationwide.

This was exactly what the sociologists wanted, but white parents refused to cooperate. When children from the “bad” part of town started arriving by the busload or — even worse — when white children were bused across town to black schools, whites cleared out. In just seven years, nine high schools in Baltimore went from all-white to all-black. In Montgomery, Alabama, Sidney Lanier High School, which used to educate the state’s elite, had almost no white students left ten years after the first black enrolled in 1964.

This was the pattern everywhere. From 1968 to 1988, the Boston school district went from nearly 70 percent white to 25 percent white. Over the same period, the drop in Milwaukee was from nearly 80 percent to under 40 percent, and in San Diego from nearly 80 percent to just over 40 percent. In only eight years, from 1968 to 1976, a staggering 78 percent of the white students left the Atlanta public schools, while white enrollment in Detroit and San Francisco dropped by 61 percent. By 1992, only 15 percent of the students in the Houston public schools were white. These dry statistics reflect tremendous disruption in countless communities, as whites pulled up stakes and headed to the suburbs or as wives went to work to pay for private school.

In 1991, the Supreme Court began to relieve the pressure on public schools to assign students by race, and subsequent decisions left only a few permissible grounds for racial balancing. However, by then, busing had transformed America’s big-city school districts into almost exclusively black and Hispanic preserves. For the year 2002-2003, those two groups accounted for the following percentages of the public schools of: Chicago — 87 percent; Washington, DC — 94 percent; St. Louis — 82 percent; Philadelphia — 79 percent; Cleveland — 79 percent; Los Angeles — 84 percent; Detroit — 96 percent; Baltimore — 89 percent. In New York City, whites were only 15 percent of the student population, about on par with Asians at 13 percent. In Dallas in 2005, the public schools were only 6 percent white.

In some areas there was a massive shift to private schools. In the Denver metropolitan area an astonishing 94 percent of white students attended private schools in 2005. A Duke University study found that in ten counties in Mississippi more than 90 percent of white students were attending private schools in 2000-2001.

It would be wrong to think that busing was a complete failure, however. Not all whites were willing to move or could pay for private school, and some welcomed integration. But national studies show that school integration peaked in the late 1980s and has since declined. Integration had the greatest impact on the South, where the number of blacks attending majority-white schools went from zero in 1954 to a remarkable 43 percent in 1988. By 2001, the figure had dropped to 30 percent, or the level of 1969.

In 1991, in the country as a whole, 66 percent of blacks attended schools where minorities were the majority. By 2004, that figure had grown to 73 percent. In Boston in 1967, the average black student attended a school that was 32 percent white; in 2003 he attended a school that was 11 percent white, and 61 percent of black students attended schools that were at least 90 percent non-white. In New York State, 60 percent of black students attended schools that were at least 90 percent black. A Scripps Howard study of US Department of Education records found that the percentage of non-white children enrolled in schools that were 90 percent non-white rose in 36 of the 50 states between 1991 and 2001. In an extensive analysis of 185 school districts with enrollments of more than 25,000, the Civil Rights Project at Harvard found that black students increased their exposure to whites in only four of those districts during the 14-year period ending in 2001.

In some cases, school districts came almost full circle. In 1953 in Atlanta, just before the Brown decision, there were 600 public schools serving 18,664 students. Blacks and whites were kept apart by law. Fifty years later, there were 96 much larger schools serving 55,812 students; more than three quarters were in schools where one race was the majority by at least 90 percent.

Gary Orfield is co-director of Harvard’s Civil Rights Project, and has been tracking schools for more than a decade. “We’re in a major process of re-segregation,” he said. “There is a cowardice about this issue. People are afraid to talk about it because it is so sensitive. So we are slipping back into separate-but-equal schools . . . . ”

At one time, “magnet schools” were supposed to solve the problem of white flight. The plan was to make urban public schools so attractive they would lure back whites who had fled to the suburbs. This policy has been an almost uniform failure, and Kansas City, Missouri, is only the most striking failure. A federal judge took over the school district in 1985, and imposed taxes to pay for the most grandiose public schools in America. Over the next 12 years, the city spent nearly $2 billion. Kansas City got 15 new schools with such things as an Olympic-sized swimming pool with an underwater viewing room, television and animation studios, a model United Nations with simultaneous interpreting equipment, a robotics lab, a planetarium, a mock court room with jury deliberation rooms, and field trips to Mexico and Senegal. A former Soviet Olympic fencing coach was recruited for a high school team. There was a $900,000 television campaign to alert whites to the remarkable new improvements. If white students were not on a bus route, the city sent taxis.

It didn’t work. By 1997, when Kansas City finally gave up, it had the most extravagant schools in the country, but the percentage of white students was lower than ever and blacks’ scores had not budged.

Whites simply do not want to send their children to school with blacks. In San Francisco, a study of the school choice program by U.C. Berkeley found that the schools with the most blacks were in least demand. Chris Rosenberg, who had been with the heavily-black Starr King Elementary School for 12 years, had seen it over and over: “When people come into some schools and they see a bunch of black kids, I can see it in their faces — ‘Thanks, but no thanks’.”

San Francisco’s 55,000-student district rapidly began to resegregate in 2001 after a lawsuit overturned race-based student assignments. In 2001-2002, there were 30 schools in which one race made up 60 percent or more of at least one grade. By 2005-2006 there were 50 such schools. Nor was it only whites who would not go to school with blacks. Tareyton Russ, principal of the heavily-black Willie L. Brown Jr. College Preparatory Academy explained that “poor Chinese kids don’t want to go to school with poor black kids [either].”

Hazelwood West High School, just north of Saint Louis, Missouri, went through dramatic changes when four new middle schools opened in the area, leading to large-scale shifts of students and resources. From 2002 to 2007, black enrollment increased 32 percent while white enrollment dropped 32 percent. The blacks moving in were from middle- and upper-middle-class families but whites left anyway. Hazelwood West’s principal Ingrid Clark-Jackson dismissed rumors that the school had a gang problem. “It has a race problem,” she explained.

An unwillingness to associate with blacks is usually considered a sign of lower-class closed-mindedness, but a recent study by Michael Emerson and David Sikkink of Rice University suggests otherwise. They found that the more education white parents had, the more likely they were to rule out schools for their children simply because of the number of blacks. Only after they had eliminated heavily-black schools did they then compare the remaining schools’ test scores and graduation rates. “Our study arrived at a very sad and profound conclusion,” said Dr. Emerson. “More formal education is not the answer to racial segregation in this country.”

Whites don’t want their children in school with large numbers of Hispanics either. In most big cities, whites have not even noticed the influx of Hispanic students because they left the public schools to blacks in the 1970s and 1980s. It is a different matter when Hispanics arrive in rural areas with few blacks. “White flight” has come to places that had never experienced it.

Meatpacking plants in Nebraska towns such as Schuyler, Lexington, South Sioux City, and Madison have drawn many Hispanic workers, whose children attend public schools. In Schuyler, for example, the Hispanic influx pushed total enrollment up 19 percent from 1993 to 2003 — while white enrollment dropped in half. Most whites did not move away, however. They took advantage of a Nebraska law that lets students attend outside their home districts, and they formed carpools to ferry their children to schools where whites were still the majority. Nebraska State Senator Ron Raikes, who called white flight “unconscionable,” promised to introduce a bill to stop parents from switching children out of their home districts.

White flight usually means better schools for the flyers, but not always. Monta Vista High School and Lynbrook High School in Cupertino, California, are known for their stellar academic records — but whites have almost disappeared there, too. White families who do not move away send their children to private schools, and whites with school-age children avoid Cupertino entirely. Why? The schools are almost 100 percent Asian. Whites tend to think Asians are grinds with no social life, but there is a deeper problem. As superintendent Steve Rowley explained, “Kids who are white feel themselves a distinct minority against a majority culture.”

Whites in San Francisco also began avoiding schools that became heavily Chinese. They feared the academic competition would be too intense, and that their children would be cultural minorities.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that all schools are starkly segregated. Evanston Township High School, in the North Shore Chicago suburb of Evanston, is a rare example of what Brown was supposed to bring to everyone: It is 48 percent white, 39 percent black, and 9 percent Hispanic. The school of 3,100 students carefully balances the races in home rooms and gym classes, and holds special events to celebrate diversity.

But like so many other schools, Evanston Township High has discovered that getting students of different races in the door is not the same thing as getting them to mix. Students gravitate to different sports teams and clubs, eat lunch at segregated tables, and even leave school by different doors. Basketball players and cheerleaders are almost all black, while the swimming and water polo teams are almost all white. Whites dominate in music, theater and art. The challenging classes are so overwhelmingly white that “you can look in a room and know if it is an honors or regular class by the color of the students’ skin,” explained senior Nicole Summers. As sophomore Paul Schroeder summed up, “We all go to the same school, but that is pretty much it.”

Many schools are therefore integrated only on paper. Kim Davis, a white senior at Palmetto High School in southern Florida explained how students socialize: “Here it’s very cliquish,” she said. “The whites hang out with the whites; the blacks hang out with the blacks.”

During the 1990s, Montclair, New Jersey, with a population that was just over 30 percent black, was a New York City suburb favored by people who wanted racial diversity in their lives. Many of their children did not. “Diversity for me means that I sit next to a black in homeroom,” said a white girl at Montclair High School, which was 52 percent black. “It’s really an aberration when I have any meaningful contact with a black kid.” A black girl echoed her sentiments: “Interracial dating? No way.”

At Toombs County High School in Lyons, Georgia, separation was formalized in a tradition of segregated proms that began in the 1970s. In 2004, the school added a third prom — for Hispanics. Principal Ralph Hardy said the tradition had nothing to do with race, simply with different tastes in food and music.

Turner County High School in Ashburn, Georgia, got its first integrated prom in 2007, although the traditional white prom took place as well. As one recent graduate explained, “The white people have theirs, and the black people have theirs. It’s nothing racial at all.”

Taylor County High School in Butler, Georgia, broke with a 31-year tradition in 2002 and tried an integrated prom. In 2003, the 55-percent black 45-percent white school switched back to separate proms.

Segregated proms are not uniquely Southern. The Solomon Schechter School of Westchester, New York, announced that no non-Jewish dates would be allowed at the Junior Ball. Gann Academy in Waltham, Massachusetts, did not issue a ban on gentiles but urged students to consider the school’s “commitment to Jewish continuity” when they chose dates for dances.

Petersburg High School in Petersburg, Virginia, was integrated in the early 1970s, but class reunions, which the alumni organize themselves, have been segregated, reflecting the reality of what it was like to be a student. As of 1997, no one objected to the divided reunions or expected them to be united in the future.

No combination of races appears to intgrate comfortably. Bolsa Grande High School in Garden Grove, California, is 52 percent Vietnamese and 37 percent Hispanic, and teachers try to keep an underlying current of hostility in check. Seventeen-year-old Ivan Hernandez explained that conflicts can be avoided when groups stay apart. “People tend to stay with their own culture,” he said. “I really don’t know many Vietnamese because I don’t hang out with them.”

“That seems to be a pattern that’s happened all over the country,” said Will Antell, a former desegregation official for the state of Minnesota. When races separate “they’re coming back to join their cohorts. . . . It’s on being with young people like themselves.”

Many schools try to encourage mixing, but students often pay no attention. A black student, LaShana Lee, wrote about how her Atlanta school celebrated Mix It Up Day, a national project that encourages students to cross racial boundaries:

“Mix It Up Day was just another failed attempt to get all students to ‘step outside the box.’ No one was really willing to sit with different people. Everyone took it as some sort of joke, and the majority of students understood we wouldn’t actually participate.”

Researchers have found that successful integration inhibits racial mixing. If a school has only a few minority students they have no choice but to mix with the majority. “When you get larger minority populations, they reach a size where you can have a viable single-race community,” explained James Moody of Ohio State University, who studies school integration. “At that point, students find enough friends within their own race and don’t tend to make cross-racial friendships.”

He noted that the best way to prevent teenagers from choosing friends of the same race is to steer them into racially mixed extra-curricular activities because people may make friendships across racial lines if they have interests in common. Another way is to segregate schools as much as possible by grade. This way, people who like to skateboard, for example, have to make friends within their own grade rather than find same-race friends in different grades.

The proportions of the racial mix seem to make a difference in how blacks and whites get along. Race relations are best when whites are a small minority, since whites do not try to assert themselves and must conform to black-majority standards. Black-white relations are reportedly worst when schools are 20 to 40 percent black.

Some schools practice a deliberate kind of segregation. Administrators often have to explain to parent groups that the white and Asian students are doing better academically than the blacks and Hispanics. Mary Perry of EdSource, a nonprofit group that researches education problems in California, explains it can be helpful to invite black and Hispanic parents to separate conferences to talk abut test scores. “Sometimes it’s more difficult to have a productive discussion when people’s perspectives are so far apart,” she explained.

This is the policy of principal Philip Moore of T. R. Smedberg Middle School in Sacramento, California. “I want people to feel comfortable,” he said, explaining that sessions are more productive when they are segregated.

Because there is such a demand for segregated schooling, some schools offer it on the sly. Whites fled the Dallas public schools when a judge ordered integration in 1971. The district tried to entice them back with magnet schools but that did not work, and Preston Hollow Elementary School became an overwhelmingly black and Hispanic school in the middle of a wealthy, white neighborhood. Over a period of several years, however, white students drifted back to Preston Hollow, thanks to an unwritten policy of grouping whites into “neighborhood” classes in a separate wing. The PTA printed up school brochures full of photographs of white children, and when white parents toured the school, teachers did not take them through the black and Hispanic wings. Increasing numbers of affluent whites started sending their children to Preston Hollow, became active in the PTA, and raised money for new library books and playground equipment.

As a practical matter, this could be considered a success, but it happened to be illegal. A Hispanic parent sued. When an inspector came by, Principal Teresa Parker mixed up the classes to give the impression of integration. When the truth came out, lawyers for the school argued that no one was hurt by the separation because all students got the same curriculum. A judge disagreed, and ordered Miss Parker to stop segregating the children and to pay $20,200 to the plaintiff. Miss Parker was reassigned to administrative duties.

Although virtually all politicians and commentators denounce school segregation, they have been known to make a virtue of it. In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling that forbade Texas universities to take race into consideration when accepting students. There was a sharp drop in non-white admissions, but Texas legislators quickly found a way to raise them. They passed a law requiring state universities automatically to admit the top ten percent of the graduating classes of all Texas high schools. Since everyone knew the high schools were segregated, this restored the effect of racial preferences. The state of Florida set up a similar system, according to which the state’s ten public universities automatically granted admission to anyone in the top 20 percent of any high school graduating class.

These measures encourage segregation. Ambitious blacks or Hispanics who want to go to Texas or Florida universities are better off in segregated rather than integrated or majority-white schools, because they have a better chance of making the cut for automatic admission.

This is the policy of principal Philip Moore of T. R. Smedberg Middle School in Sacramento, California. “I want people to feel comfortable,” he said, explaining that sessions are more productive when they are segregated.

Because there is such a demand for segregated schooling, some schools offer it on the sly. Whites fled the Dallas public schools when a judge ordered integration in 1971. The district tried to entice them back with magnet schools but that did not work, and Preston Hollow Elementary School became an overwhelmingly black and Hispanic school in the middle of a wealthy, white neighborhood. Over a period of several years, however, white students drifted back to Preston Hollow, thanks to an unwritten policy of grouping whites into “neighborhood” classes in a separate wing. The PTA printed up school brochures full of photographs of white children, and when white parents toured the school, teachers did not take them through the black and Hispanic wings. Increasing numbers of affluent whites started sending their children to Preston Hollow, became active in the PTA, and raised money for new library books and playground equipment.

As a practical matter, this could be considered a success, but it happened to be illegal. A Hispanic parent sued. When an inspector came by, Principal Teresa Parker mixed up the classes to give the impression of integration. When the truth came out, lawyers for the school argued that no one was hurt by the separation because all students got the same curriculum. A judge disagreed, and ordered Miss Parker to stop segregating the children and to pay $20,200 to the plaintiff. Miss Parker was reassigned to administrative duties.

Although virtually all politicians and commentators denounce school segregation, they have been known to make a virtue of it. In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling that forbade Texas universities to take race into consideration when accepting students. There was a sharp drop in non-white admissions, but Texas legislators quickly found a way to raise them. They passed a law requiring state universities automatically to admit the top ten percent of the graduating classes of all Texas high schools. Since everyone knew the high schools were segregated, this restored the effect of racial preferences. The state of Florida set up a similar system, according to which the state’s ten public universities automatically granted admission to anyone in the top 20 percent of any high school graduating class.

These measures encourage segregation. Ambitious blacks or Hispanics who want to go to Texas or Florida universities are better off in segregated rather than integrated or majority-white schools, because they have a better chance of making the cut for automatic admission.

After four years of separation, minorities can graduate in separate ceremonies. At the University of California at Los Angeles, it has become a bit of a trick to schedule all the ethnic graduations. There is one for blacks, one for Chicanas/Chicanos, and one for the entire Hispanic raza. UCLA used to make do with an Asian-Pacific Islander ceremony, but now it has separate graduations for Filipinos and Vietnamese, and there was talk of one for Cambodians. Outside of California, there may not be enough Filipinos or Vietnamese for a separate ceremony, but special graduations for blacks are common.

Some blacks assume their university will support any exclusionist fancy. At Boston’s Northeastern University in 2005, the director of women’s studies, Robin Chandler, advertised a four-hour “Women of Color Dialogue” that was to be closed to whites. After a protest from the Student Government Association, the provost ordered the session open to white women (men were still kept out). Dr. Chandler was annoyed:

“I think it’s a shame that one or two white students based on white privilege, a lack of awareness of racial issues and a lack of generosity of spirit complained to the office of the provost and were able, because they were white, to gain admission to the morning session that I was forced to open up. Only one white female student showed up and I welcomed her anyway, in addition to telling the audience to conduct themselves with integrity even though the presence of a white woman was unwelcome.”

A graduate of Northwestern University near Chicago summed up what may be a common experience. When asked by Newsweek about racial hostility on campus, she replied, “I don’t remember any overt racial hostilities. You need a certain amount of contact to have hostilities.”

Specific Objectives

School integration has clearly not proceeded as planned. It is also worth noting that when there has been integration, it has not achieved its objectives. Although the larger purpose was to solve the American dilemma, school integration had three specific goals of its own: It would lift black academic achievement, raise black self-esteem, and give black and white children better impressions of each other. There have now been hundreds of studies of the effects of integration, and none of these goals was achieved.

With respect to academic improvement, an exhaustive 2002 survey reported, “there is not a single example in the published literature of a comprehensive racial balance plan that has improved black achievement or that has reduced the black-white achievement gap significantly.” A recent book devoted entirely to the racial gap in school achievement concluded:

“Whether African-American students attended schools that were 10 percent black or 70 percent black, the racial gap remained roughly the same . . . . If every school precisely mirrored the demographic profile of the nation’s entire student population, the level of black and Hispanic achievement would not change.”

Self-esteem studies have not produced what liberals expected either. Blacks, in general, have higher levels of self-esteem than whites, and integration appears to lower it. The most likely reason for this latter finding is that black children generally do not perform as well in school as white children, and they come face to face with the achievement gap only in integrated schools.

Findings on relations between the races also disappoint integrationists. Studies generally gauge the attitudes of white students towards blacks before and after attending integrated schools. A summary of results shows that after integration, whites are as likely to have a worse view of blacks as they are to have an improved view. These, moreover, are the findings for whites who have stayed in integrated schools, and are probably more likely than those who left to have a favorable view of blacks.

The advocates of school integration thought it would succeed because they believed children do not see race. They were wrong. Children separated themselves by race even in places such as Shaker Heights and Montclair, where parents wanted them to mix. Many children, however, had no choice in the matter because their parents moved to the suburbs or put them in private schools. It was both parents and children, therefore, who defeated integration.

Now that the Supreme Court has virtually ruled out race-based student assignment, the country is reverting to neighborhood schools that are not legally segregated but that reflect self-segregated housing patterns. This has reduced integrationists to a position almost identical to that of Gunnar Myrdal in 1948. As Brian Stults of the University of Florida at Gainesville explained: “It’s sort of a chicken-and-egg problem: We need integration in schools to lessen prejudice, which will then reduce residential segregation, but in order to have school integration, we need residential integration.”