White Men Meet Indians

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, January 2004

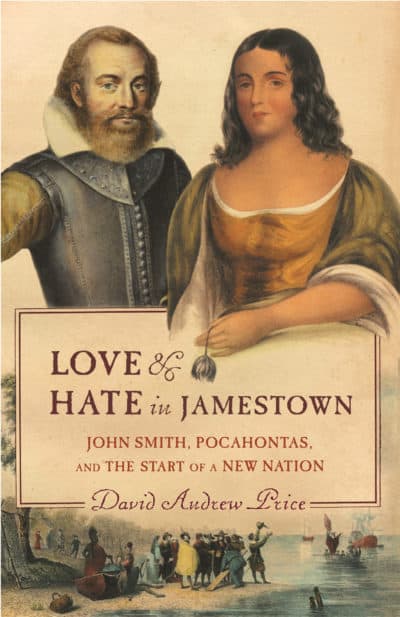

Love and Hate in Jamestown: John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Heart of a New Nation by David A. Price, Alfred A. Knopf, 2003, 300 pp.

Everyone has heard of Jamestown, Captain John Smith, and Pocahontas, but most Americans know few details about the clash of races and civilizations that marked the arrival of the English in Virginia in 1607. Love and Hate in Jamestown is a fascinating, readable account of the early days of the colony that treats the cultural collision with none of the anti-white hysteria now common in historical writing. Author David Price clearly admires Captain John Smith, and though many of the other Englishmen he writes about were greedy, naïve, or lazy, they came seeking better lives, not conquest or domination. In today’s terms, Jamestown was a port of entry for illegal immigrants. What followed was an early exercise in diversity that brought tragedy for the English and oblivion for the Indians. It has lessons for us today.

Strictly Business

The Virginia Company of London had no romantic or swashbuckling pretensions. It was a money-making venture with three aims: to find gold, discover a passage to the Pacific, and — a distant third — bring Christianity to the natives. The 105 colonists who arrived in 1607 were so sure of finding gold they entered into what now seem very reckless contracts: In exchange for a one-way ticket to America and a share in the profits, they bound themselves to a set period of service in Virginia — it appears to have been seven years — during which they received no pay, had to obey orders, and could not leave. There were no women in this first group.

Unlike the Spaniards, who had a reputation for massacre, they were determined to treat the Indians lovingly. They would bring civilization and Christianity so that, as one of the company’s backers wrote of the natives he had never met, “Their children when they come to be saved, will blesse the day when first their fathers saw your faces.” About half the colonists were “gentlemen,” with no experience or expectation of manual labor, but all were in for a shock. As Mr. Price writes, they arrived “with pure hearts and empty heads, expecting to find riches, welcoming natives, and an easy life on the other shore.” Most were dead before the year was out.

The passage to the New World should have been a sign of trouble to come. It took from January 5 to March 23 to get to the West Indies, and another month to sail the 1,500 miles north to Virginia. Along with 39 sailors, the men were crammed into three small ships, of which the largest was only 15 feet across at its widest point. There were sharp disagreements on board, the nature of which have not been recorded, and the leaders of the expedition kept John Smith prisoner for most of the voyage. During a stop at a Caribbean island they even built a gibbet for him, but with his usual knack for survival he talked his way out of the noose.

On April 26, the ships reached Virginia, and the colonists quickly met Indians. The initial contacts are well recorded, as are the English attitudes to what they referred to as “the naturals.” Both are instructive, and are hardly consistent with the now-standard image of rapacious colonization. Mr. Price emphasizes that the colonists had entirely benevolent intentions. “The English,” he wrote “did not believe that white people like themselves were innately superior and the natives innately inferior [since] savagery was only the starting point for a people’s progression toward modernity.” He explains further: “The English did not exclude themselves from the progression: in the days of the Roman conquest, as the English now saw it, the Britons themselves were savages. The civilizing influence of the Roman conquerors, and later of the Christian gospel, had lifted the English up from savagery. Supporters of the colony expected it to bestow the same benefits on the natives. . . .”

Mr. Price adds that the English thought of the Indians essentially as white people, unlike Moors or black Africans, whom they considered fundamentally different from themselves. At first, they were convinced Indians were born white, but that constant painting discolored their bodies. The English were careful to settle only on uninhabited land, and looked forward to trade and cooperation. It was clearly the Indians who, not unnaturally, saw the colonists as invaders and were determined to dislike them.

There was trouble the first day ashore. As the English were returning to the beach, a band of five Indians ambushed them with bow and arrow, wounding two. The English chased them off with musket fire but hit no one. Smith, who observed the engagement while still a prisoner on board ship, noted that the Indians’ weapons were more accurate than muskets, and that their rate of fire was faster.

The next day, the English met no natives but they found oysters cooking over a fire, which Indians had obviously left behind in a hurry as the strangers approached. The colonists helped themselves, and found the oysters “very large and delicate in taste.” Several days later, they met Indians, and succeeded in making gestures of peace. The Indians led them to their village, fed them, and performed a dance, which involved, in the words of one visitor “shouting, howling, and stamping against the ground, with many antic tricks and faces, making noise like so many wolves or devils.”

The English spent about two weeks looking for a place to settle. They met various tribes — some friendly, some not — but there was no bloodshed. On May 14, they chose the present site of Jamestown, and the leaders finally released Smith from confinement, since all hands were needed to help build the settlement. The colony president, Edward-Maria Wingfield, decreed that since the English came in peace there would be no fortifications and no training in the use of weapons. During the first few days, Indians made friendly visits, fascinated by metal weapons, tools, and the trinkets the colonists brought to trade.

On the fourth day, a chief named Wowinchopunck arrived with about 100 armed men. The English nervously readied their weapons, and there was a standoff. An Indian picked up an English hatchet and refused to put it down. There was a scuffle, and the chief “went suddenly away with all his company in great anger.”

Shortly afterwards, 23 men including Smith set out to do the company’s work of looking for gold and a passage to the Pacific. On this trip they learned of the extent of what was called the Powhatan empire. The great chief controlled the entire eastern part of what is now Virginia, and though local tribes had some autonomy, he had firm control.

The exploring party found no gold and no route to the East, and had another disappointment when they returned on May 26. Just the day before, hundreds of natives had attacked the settlement, killing an English boy and wounding a dozen men, one of whom later died. The colonists managed to panic the attackers with canon fire — without which they might well have been massacred — and killed at least one Indian. These were the first deaths on both sides. Jamestown was not even two weeks old.

Wingfield decided the settlement would have to be fortified after all, and the men built the triangular palisade with gun emplacements at the corners now familiar to school children. From that point on, there were sporadic attacks, but no deaths for another week. On May 31, a man who had been outside the palisade came running back inside with six arrows stuck in him, and died a week later.

Not all contact with Indians was violent. The English learned that it was the Paspahegh tribe, their nearest neighbors, that most disliked them. Although the English thought they had settled on unclaimed land, the Paspahegh considered it theirs. Indians who lived farther away were more friendly and willing to trade. This was the reverse of what the English had hoped for — it was the Indians with whom they had most contact who liked them least.

On June 22, the sailors, who were not subject to Virginia Company rules, set sail for England. They had been the most productive workers, and for reasons that are not entirely clear, work on the settlement all but stopped. The “gentlemen” refused to work, but so did many others. Everyone seems to have thought the ships were going to come back full of food. As Smith wrote in disgust, the colonists were “in such despaire as they would rather starve and rot with idleness, then be perswaded to do anything for their owne reliefe without constraint.” Freeloading was a big problem. Everyone shared the common food supply, so there was little reward for individual effort.

The summer brought several nasty surprises. Jamestown was marshy, and what had been good drinking water in April turned brackish in June. Mosquitoes brought malaria. The stores from England began to run out, but anyone who went hunting risked being killed by Indians. Men began to die from disease and malnutrition. At times only five men were strong enough to stand guard or drag the dead out of the fort. Nearly half the colonists died, and the rest expected to be massacred. To their surprise, Indians came to trade food for beads and hatchets. Chief Powhatan appears not to have realized how weak the English were, and how easily he could have exterminated them. At this low point, the colony elected John Smith as its leader. He tightened up discipline, and established the rule that those who did not work would not eat.

That winter, after the men had recovered somewhat from sickness, Smith set out again to hunt for gold and the Pacific. It was on this trip that he had his famous encounter with Pocahontas. At one point he split his party in two, leaving seven men on a boat with strict orders not to venture onto land where they could be ambushed. However, Chickahominy warriors set out women on the shore, and had them gesture pleasingly to the English. They went ashore, only to be attacked, and all but one, George Cassen, scrambled back to the boat. This, as Mr. Price tells it, is what happened to Cassen:

“The natives prepared a large fire behind the bound and naked body. Then a man grasped his hands and used mussel shells to cut off joint after joint, making his way through cassen’s fingers, tossing the pieces into the flames. That accomplished, the man used shells and reeds to detach the skin from Cassen’s face and the rest of his head. Cassen’s belly was next, as the man sliced it open, pulled out his bowels, and cast those onto the fire. Finally the natives burned Cassen at the stake through to the bones.”

While this was going on, Indians attacked Smith’s group, killed his companions, and captured Smith. The men brought him to one of Powhatan’s younger brothers, Opechancanough, who would play a significant role in later years. It appears to have been a very near thing whether Smith would be carved up and burnt in pieces, too, but he claimed to be a chief, and it was not the custom to torture chiefs. Opechancanough decided to take him back to Powhatan for a final verdict, but marched his captive from village to village for several weeks before taking him before the chief of chiefs.

Smith began to understand that Opechancanough wanted to attack Jamestown, so he lied stoutly about its defenses. He also persuaded his captors to let him send a message back to Jamestown, claiming that if his men thought he was harmed they would come and wreak terrible vengeance (Smith had an unusual gift for bluffing; the colonists were in no state to mount a punitive expedition). He wrote on a page from his notebook that the colonists were to terrify the Indian messengers with a demonstration of cannon fire, and to send back certain gifts. The messengers came back suitably terrified, and astonished that the colonists had given them exactly what Smith said they would. They had no writing, and thought Smith had made the piece of paper talk.

Smith spent Christmas as a prisoner, and did not meet Powhatan until the new year. He estimated the great chief to be in his sixties or seventies, and was greatly impressed by his bearing and aura of command. Powhatan wanted to know what the colonists’ intentions were, and Smith lied again, saying they had come ashore only after losing a battle on the seas with enemies, and would go back to England soon. He bragged again about how vengeful the English were, implying that Powhatan had better treat him well or reap the consequences.

It didn’t work. Powhatan ordered his men to force Smith’s head down on a large rock and dash out his brains. It was then that Pocahontas, age 11 or 12 and the favorite of Powhatan’s many children, scampered out of the crowd, put her head over Smith’s and begged for his life. Smith believed it was nothing more than a gesture of kindness from the child, who had a lively curiosity and wanted to know more about this strange visitor rather than see him executed. Powhatan agreed to spare his life if Smith would promise to send two cannon and a grindstone. Smith could hardly decline.

On his return to Jamestown on January 2, 1608, Smith found the colony in a bad way. There had been more Indian attacks, and only about 40 of the original 105 settlers were still alive. Several had taken over the remaining ship, and were about to sail back to England. Company rules forbade defection, and Smith trained cannon on the ship to prevent escape.

He also had to deal with the 12 men Powhatan had sent back with him to haul home the grindstone and cannons. Smith, who had a sense of humor, offered the men two culvereins, which weighed about 3,000 pounds each. The Indians could not even lift them, much less drag them through the woods, and left without them.

Such were the contacts with the Indians during the first half year of the Jamestown colony. The English meant no provocation, but their very presence was a provocation. From time to time Indians found it useful to trade with the colony, or to enlist its help in quarrels with enemies, but their abiding attitude was hostility. Many men back in England — and many who came later to Virginia — continued to believe harmonious relations were possible with the “naturals,” but Smith soon understood uneasy toleration was the best the English could expect.

Still, there were gestures of amity. The English left a boy in Powhatan’s village to learn Indian ways and master the language. The Indians left a boy with the English, who was later taken to England for exhibition by the Virginia Company as one of its many money-raising schemes. Pocahontas took to visiting Jamestown, where she played with the English boys, and got better acquainted with Smith.

Throughout this period, the English were still convinced they would find gold. They sent boatloads of fool’s gold back to England, and the company sent miners to Virginia. Once again, Mr. Price tells us, Smith was among the first to shake off illusion. He laughed at the “gilded dirt” the English kept bringing in, reasoning that if there were gold nearby, the natives would have found it just as the South Americans had before the Spanish arrived.

During the spring of 1608, as the colony marked its first year of existence, there were no all-out attacks by Indians, but Powhatan proposed to trade turkeys for swords. Smith, who had no intention of arming a potential enemy, said no. Powhatan started sending small parties of men to try to steal things, and at one point the English caught and locked up a dozen thieves. Smith sent a message to Powhatan, saying that if the spades, shovels, swords, and tools the Indians had stolen were not returned, he would hang the prisoners. The Indians then caught two colonists and proposed an exchange.

Smith, his numbers reinforced by a new installment of colonists, went on a punitive expedition, in which he killed no one, but burned villages and destroyed canoes. Powhatan returned the two colonists. Smith learned from his Indian prisoners that Powhatan planned to hold a feast for the English, kill them while they were off guard, and take all their weapons and tools. Smith released the prisoners, but his bluster and resolution seem to have cowed them. For a time there was uneasy peace.

Mr. Price recognizes the wisdom of Smith’s firm approach to the Indians. These were not gentle children of nature yearning for Christianity. “The alternative to intimidation was not love and friendship,” he writes, “it was open war — which the English, in 1608, would have lost to the last man.”

Smith sent frank letters back to the company, explaining that Virginia was a failure as a get-rich-quick scheme, that sending over titled layabouts to look for gold was folly. It was a rich country, he explained, but one suited for farmers and fishermen rather than gold miners. His messages began to sink in and the company began to send more suitable colonists.

Powhatan seems to have vacillated between trying to starve out the English and seeing what he could get out of them by trade. By the winter of 1608, the colonists were nearly out of food. Powhatan offered grain in return for an English-style house, guns, swords, copper and beads. Smith was desperate for supplies, and accepted the offer except for the weapons. Then followed what may have been the first act of European race treachery on North American soil.

Smith sent more than a dozen tradesmen to build Powhatan’s house, including two German glass-makers for the windows. The Germans, who had never been to Powhatan’s village, were impressed by the large stores of food, and decided to go over to the Indians. They told Powhatan about Jamestown’s defenses, and offered to go back to the colony and steal weapons.

Meanwhile, when Smith showed up for the food, Pocahontas once again saved his life by warning him about a plan to kill him and his men when they had set their weapons aside to eat. They kept their weapons at the ready while they ate, as the strapping, fierce-looking men who had brought the meal looked on in obvious frustration. Smith returned to Jamestown with enough food to tide the colony over the winter.

During their trips to Jamestown to steal weapons, the Germans persuaded six or seven Englishmen to gather weapons and help arm the Indians. Early in 1609, Smith learned about the treachery. With uncharacteristic forbearance, he offered to pardon the Germans if they came back, and they accepted. After a month in Jamestown, however, they went back to Powhatan and offered to turn their coats again. They told him about plans for a new shipment of several hundred new colonists, and offered to collect information on the grandee who was coming to replace Smith. Powhatan is reported to have said, “You that would have betrayed Captaine Smith to mee, will certainely betray me to this great lord. . . .” He then had his men beat out their brains with clubs.

Smith continued to explore, getting as far as Delaware, and the future site of Washington, DC. However, by 1609 he had made so many enemies among the gentlemen that the company cashiered him and brought him back to England. He never returned to Virginia. By this time there were about 500 people in Jamestown, but the newcomers were still, as Mr. Price explains, “looking forward to lives of idle leisure supported by supplies from London, food from the natives, and gold from the ground.” This was because the Virginia Company strictly controlled all news about the colony, even censoring private letters, so as not to discourage potential investors and colonists with tales of torture and starvation. The deluded colonists were still not growing enough food to feed themselves.

After Powhatan had met the incompetents who replaced Smith, he began attacking the colony again with surprise raids. His men massacred a party of English who went looking for food, and left their bodies for the others to find, with bread stuffed in their mouths.

A ship that went out to trade with Powhatan came back empty, and with only 16 of the 50 men who had set out on the trip. The commander had not taken the usual precautions with the Indians, and got the usual treatment of slow dismemberment and burning. “And so for want of circumspection [he] miserably perished,” recorded one of his contemporaries.

During the winter of 1609-1610, which came to be known as “the starving time,” Powhatan nearly succeeded in wiping out the colony. By March 1610, 400 out of the 500 Smith had left behind were dead of starvation or Indian attacks. Another 36 stole a boat and did a flit back to England. The English were so hungry they ate their dead comrades, and one man even killed and ate his pregnant wife. Once after an Indian attack, the English buried a dead Indian, but several days later, regretting their improvidence, dug him up and ate him.

The colony came within a hair’s breadth of abandonment, and Mr. Price tells the dramatic story of how the English were saved. He goes on to tell of Pocahontas’s kidnapping, her conversion to Christianity, and her 1614 marriage to John Rolfe, which brought peace with the Indians. Mr. Price also mentions the arrival in 1619 of the first Africans, noting that the English did not have any illusions that they were potentially white: “Notions of black racial inferiority seem to have been firmly in place in the colony from the start.”

During this time of peace with the Indians, the authorities threw themselves again into the idea of loving and Christianizing the “naturals.” They set aside 10,000 acres of land on the site of Pocahontas’s conversion, to be used as a Christian college for Indians. A leader named George Thorpe was particularly solicitous of Indians. Unlike in the old days, they came and went freely in the colony and in the satellite colonies that sprang up along the river banks. When Indians complained that dogs were frightening them, Thorpe had the dogs publicly hanged. Thorpe even had an English-style house built for Opechancanough, brother of Powhatan who captured Smith, and who became the new chief after Powhatan’s death in 1618.

Opechancanough did not, however, have a favorite daughter married to an Englishman. He resented the steady growth of the colony, and hatched a plot to be rid of it. On March 22, 1622, Indians arrived among the English, unarmed as usual, taking their places at breakfast tables and workplaces. However, when the colonists were least suspecting it, they rose up and killed as many as they could with anything they could get their hands on. Fortunately for the colony, the main population at Jamestown got warning early that day. The men kept their arms by their sides, and the Indians did nothing. Elsewhere, they achieved complete surprise, slaughtering and mutilating men, women, and children. To Thorpe, their celebrated benefactor, they “did so many barbarous despights and foule scornes after to his dead corpse, as are unbefitting to be heard by any civill eare,” according to a contemporary chronicler. Of an estimated 1,200 colonists, the Indians managed to kill about 400.

This was a great setback for the colony, but the English spent a year making war on the Indians, and in March 1623, Opechancanough sued for terms. The English pretended to agree, and brought a great cask of wine to the peace celebration. After much friendly speechifying, the Indians drank the wine — poisoned by the English — and about 200 died. Later that year the English signed a real peace treaty with Opechancanough, and the two peoples gradually returned to their old ways of peaceful intercourse.

Amazingly, in 1644, Opechancanough masterminded an identical sneak attack, and this time managed to kill between 400 and 500 people. The impact was not as great, since the colony had grown bigger still, but this time the English did not stop until they had killed a great many Indians, including Opechancanough. In 1646, the Virginia General Assembly noted that the natives were “so routed and dispersed that they are no longer a nation, and we now suffer only from robbery by a few starved outlaws.”

Other Outcomes?

It is clear from Mr. Price’s account that the English approached the Indians with about as much goodwill as it is possible for one alien people to approach another. To have established the conditions that made it possible for the Indians to mingle so freely with the colonists they could manage the massacre of 1622 shows a high level of trust, which the Indians brutally betrayed. For the English to have then so lowered their guard that the same Indian chief could slaughter another 500 colonists 21 years later in exactly the same way, again shows how much the English were prepared to trust their neighbors. Had the Indians taken the same benevolent view of the English, it is possible to imagine peaceful trade, missionary work, and perhaps even large-scale miscegenation and eventual absorption. The colonists, for their part, seem to have brought to Virginia no preconceptions that would have prevented such a result.

For the Indians, however, the English brought no possible outcome — be it conversion, assimilation, or absorption — that meant anything but their destruction as a people. In delaying their all-out assault on the colony until there were too many English to exterminate, they ensured their own physical rather than merely cultural or genetic destruction. Even if they had succeeded in wiping out Jamestown during the “starving time,” the English — or someone else — would have come eventually. By the 17th century, Europeans were too ambitious to leave an entire continent in the hands of stone-age savages.

It is instructive to note that nearly 400 years later, the whites who have now taken possession of the continent have lost none of the illusions of the Jamestown colonists. As whites, in their turn, suffer invasion by aliens they persist in believing that with enough love and generosity, the children of today’s illegal immigrants “will blesse the day when first their fathers saw their faces.” This, of course, was the illusion that led to the massacres of 1622 and 1644. It is only whites who believe in and try to practice multiracialism and peaceful coexistence.

The future probably holds nothing so dramatic for today’s whites as the Jamestown massacres, but if they do nothing, what is in store for them is the gradual dispossession that awaited the Indians had they not brought about physical destruction through futile acts of violence. Yet again, whites seem prepared to pay the price for believing that others are no different from themselves