The Prophet of the Coming Age

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, March 7, 2025

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

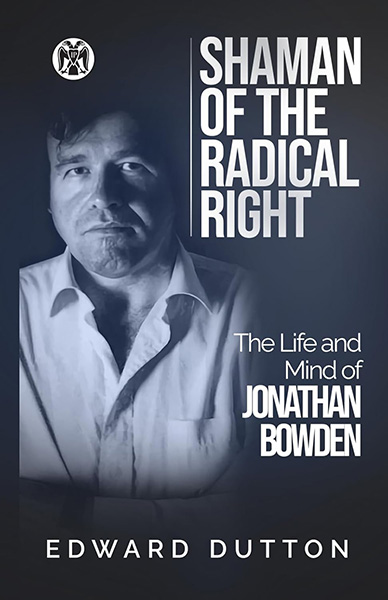

Edward Dutton, Shaman of the Radical Right: The Life and Mind of Jonathan Bowden, Imperium Press, 2025, 355 pp, $25.00 paperback, $9.99 Kindle

I was there.

Edward Dutton calls it a part of “American nationalist folklore.” In 2009, Jonathan Bowden spoke at a nationalist gathering in Atlanta. Jared Taylor introduced him. Professor Dutton quotes Alex Kurtagić:

Jonathan then hit the ground running, fast and hard, and orated for an hour. The intensity was electrifying. Everyone was paralysed. Had anyone not been too transfixed to look, not turned into a salt statue, he would have found jaws all over the floor. It felt like history being made. And who can remember what he said? Few would be able to tell you today. Something about dispelling the cloud. It doesn’t matter. It’s the way he said it that counts. It’s the energy he expelled, and what it did to the audience, that was important.

I was in the audience. There was no microphone, but Bowden had (accurately) said he had a “very loud voice,” so that was no problem. I too do not remember exactly what was said, except Bowden’s declaration that he was “not a Christian” and that life to him was struggle and pain and overcoming and glory. No one took notes, and tragically there was no recording; I cannot help but think others might remember his exact words differently, if not their effect. I have heard many speeches in my life. That speech was by far the best.

Why? With distance should come perspective. It is an unfortunate truth that in politics (dissident or mainstream) you are going to meet strange people whom you would rather avoid. On the surface, Bowden should have been one. He was overweight, wore an Odal rune on wood that clashed with his rather unfortunate fashion sense, and spoke passionately about themes of war, sacrifice, and other charged ideas that are easy to mock or dismiss when you are sitting in a hotel conference room, not a battlefield.

Countless nationalist, self-styled “leaders” have imagined themselves Tribunes of the People and have tried a similar approach, mostly with depressing or unintentionally amusing results. But Bowden succeeded so well that teenagers who were not even alive in 2009 are seeking out his speeches on YouTube, and Bowden’s declarations are common on nationalist videos on TikTok and other social media. How is this possible?

Edward Dutton answers the mystery in his magnificent new biography of Jonathan Bowden. It succeeds for three reasons.

First, Mr. Dutton did the research, tracking down eyewitness accounts, cross-referencing data, and giving us a coherent account of what exactly Bowden was doing and why throughout his life. One might object that this is essentially what every biography should be, but Jonathan Bowden presented a special challenge because of his almost unfathomable capacity for invention or, more uncharitably, deception.

Almost everything about his life, including relationships, family, where he lived, his education, and everything else, was purely invented, leaving Mr. Dutton to untangle numerous contradictory accounts, phony or misleading records, and urban legends. Bowden’s life and lies were so chaotic, they raise the question of whether he himself knew the truth. Occasionally, Mr. Dutton’s truth-telling means discrediting some beloved myths. I was especially sad to learn that Jonathan Bowden’s boast of speaking to Conservative politician Michael Gove, who supposedly told him there was just nothing to be done about mass immigration, probably is not true.

The second reason is that Mr. Dutton brings in his insights from evolutionary psychology to explain not just Jonathan Bowden, but the intellectual, genetic, and evolutionary climate that produced him. Perhaps the most tiresome trope in biographies is the lazy psychoanalysis by writers eager to pathologize or smear their subject. Mr. Dutton does something quite different. He explains why psychological disorders may even have beneficial effects.

Much of the book concerns Bowden’s troubled mental health, his baffling deception about his own life (including claims of marriage and wealth), and delusions of persecution. Yet some of this is inseparable from the creativity, magnetism, and occasional genius that Bowden possessed when he spoke. “[T]he brilliance of Bowden is inextricably linked to his flaws: being a fantasist, being Narcisscisstic, being a depressive and a paranoid schizophrenic,” Mr. Dutton writes. “To put it simply: it is rather difficult to have one without the other.”

One of the most enjoyable parts of this book is Mr. Dutton’s examination of the otherworldly philosophy of Traditionalism and the biological purposes it may serve. Much of Bowden’s genius, he argues, is that he was able to present an often complex and confusing philosophy in an “exciting and original way.” “In effect, the Traditionalist worldview seems to be taking that which is adaptive for the group — which includes conservative religious belief which has been shown to correlate with mental and physical health, fertility, ethnocentrism, and is an instinct which is activated in times of stress — and justifying it philosophically: Force yourself to believe in the eternal and that humans are nature made sentient,” Mr. Dutton summarizes.

When we dismantle our traditions or achieve a “comfortable” life, the result is not happiness, but dysphoria — a feeling that things are “not quite right” and leading to a kind of societal resignation, manifested by behavior like the refusal to have children. Seemingly irrational behavior, like resigning from the modern world, can even be a kind of “adaptive response.” Indeed, Bowden’s Traditionalism, Mr. Dutton argues, can be frightening to postmodernists because “it forces them into the real world, which their reassuring worldview tells them doesn’t even exist.” It is no small thing to take on such weighty themes, analyze their evolutionary purpose and scientific validity, and restrain from airily deconstructing them.

Throughout the book, on subjects as varied as psychopathy, BSDM, or depression, Mr. Dutton shows there is often a more complicated reality behind problematic behavior. Perhaps no other author can provide such insight on so many topics. This leads to the third great strength of the book: Mr. Dutton is clearly sympathetic to his subject and provides a compelling case for why he matters. However, this is not a hagiography. Indeed, at least one reviewer has accused Mr. Dutton of writing a hit piece. Yet the book never crosses that line. Moreover, the author shows why Bowden’s occasionally bizarre or destructive behavior can even be considered part of his appeal.

What is the nature of that appeal? One other thing I remember from the speech in Atlanta is Bowden saying that he was a “mediumistic speaker,” a self-description he repeated on another occasion. Bowden did not prepare his speeches in advance or simply read from a prepared text. Mr. Dutton argues that the near-trance Bowden seemed to enter as he spoke was a kind of disassociation. The title’s invocation of a “shaman” is not flippant, but a description of the archetype and role that Bowden embodied for the English people. “He is able to descend into the underworld, to speak with and even do battle with the spirits of the animals, and then he returns to this world, reassuring the tribe that there will be good hunting,” Mr. Dutton writes. “It has even been suggested that psychosis may well stay in populations precisely because of the way in which it creates shamans who then inspire the group, via a kind of religious fervor, towards victory over its enemies.”

Bowden was, in his way, a religious leader, and religion serves a social function. “The key point, from an evolutionary perspective,” Mr. Dutton writes, “was Bowden’s ability to entrance members of his own ethnic family and to compel them to want to keep that family going — in the face of members of it that would destroy it for their own selfish ends — and make that family great; make it fight, forever, to be one of the gods.” Rare is the man who can make such an outlandish message appeal to ordinary people; perhaps rarer still is the author who can explain why this happens, and how it works.

During Bowden’s life, whatever his undoubted charm on occasion, there were elements many would call pathetic. These include his deplorable living conditions, his failed attempts to serve in various right-wing political organizations, and his failure to have a permanent relationship. Mr. Dutton compiles many unedifying anecdotes about Bowden, notably about his overeating and awkward social behavior. His books were not very good and some were borderline unreadable, his paintings were perverse and often ugly, and his movies were amateurish. He seems to have had no lasting relationships with women. Some who knew him simply do not see his appeal.

However, in some ways, these qualities make him more attractive for the internet age. His vulnerability and awkwardness make him more sympathetic, especially to young whites who find themselves adrift in a hostile culture. Whatever his formal education, professional associations, or artistic interests, Bowden was able to integrate his undoubted erudition into spontaneous, passionate, and exciting speeches that turned complex ideas into inspiring calls for action. His lectures on Julius Evola, Léon Degrelle, and vanguardism are just as compelling as his analysis of pop culture. While probably on the autism spectrum, Bowden occasionally displayed a remarkable insight into human nature, notably about the doublethink that possesses many ordinary white people when it comes to racial issues and their attitudes toward their would-be champions. Those forever “outside” a milieu — in this case the milieu of “normal” conservatives — can often understand it better than those inside. To many, Mr. Dutton observes, Bowden’s flaws simply do not matter.

Nor should they. In the internet age, what matters is content. Jonathan Bowden gave European youth a “credo” at a time when they were being told the only meaning they could seek is through self-destruction and self-mortification. Instead, Bowden preached an amor fati that somehow did not come off as presumptuous, probably because of that strange combination of invincibility and vulnerability he seemed to possess. Mr. Dutton notes that he was especially important to the English-speaking world, serving as an invaluable bridge between the ideas of the European New Right and Anglo conservatism. He must be considered one of the intellectual founders of the original Alternative Right.

He will also be a founder of what comes next, as his influence is only growing after his death. What is perhaps most remarkable about Jonathan Bowden is the near-universal respect and awareness he has within a famously factional movement. Indeed, much of the book details Bowden’s fairly tawdry fights within many British nationalist organizations, alternately clashing and then making up with figures such as Nick Griffin. However, his speeches have transcended those now all-but-forgotten struggles. Mr. Dutton says he has encountered several young, well-educated, and stylish young rightists who look to Bowden as an inspiration, something that few would have predicted during his lifetime. In American right-wing circles, Bowden is one of the few figures who can be cited by both MAGA-supporting Republicans and Dissident Right vanguardists calling for the end of the American Empire. Both his longform speeches and his more meme-worthy declarations (“clear them out!”) are practically made for social media.

Hopefully new and normal individuals will reinvigorate the FGC scene, and any other gaming scene to be honest, once the toxic elements and the cause of it are dealt with.

As Jonathan Bowden said: “You’ve got to clear them out as well. There needs to be a new start.” pic.twitter.com/VKPBQpHhsV

— Winged Barnacle (@wingedbarnacle) February 17, 2025

If the book ended with the subject’s life, it would be terribly sad. Bowden’s psychological breakdown, partially linked to his family history, ultimately led to his being heavily medicated. According to most (but not all), this had a dramatic and deleterious impact on both his personality and speaking style. Of course, a descent into madness would have been even worse. Mr. Dutton suggests that the medicine used to treat his disorder might have interacted with an undiagnosed heart disorder leading to Bowden’s death in his sleep at age 49 on March 29, 2012. Though an oft-published author and a widely admired lecturer, Jonathan Bowden received a pauper’s funeral.

Yet Bowden’s story did not end there. The triumph and tragedy is that Bowden died when he did. I agree with the contention in the book that he would have been an internet celebrity had he lived a bit longer. His spontaneous approach might have translated well to streaming, podcasting, or interviews if he had had someone to keep him organized. That might have also gone a long way toward alleviating his financial struggles. Yet had he lived, he would have undoubtedly been sucked into the endless personal disputes and fights that characterize vanguard politics. Mr. Dutton cites several incidents that show that despite his calls for toughness and even ruthlessness, Bowden was rather sensitive to personal criticism and probably lacked the steel for continuous political debate. One would expect no less of someone who was, essentially, of a bohemian and artistic temperament.

Perhaps it is best that he died when he did, leaving a legacy as a unifying and inspirational figure whose work transcended his personal limitations. Even his demons — pitiable eccentricities rather than anything immoral or malicious — may have been a necessary price to fuel his oratory. After all, was that not the whole point of Bowden’s philosophy? Life is struggle, pain, and glory, and the acceptance of suffering must be endured to achieve even a moment of greatness. Those moments of greatness that Jonathan Bowden gave us last forever online and in the awed memories of those of us fortunate enough to have seen and heard him.

We are also fortunate that he has a biographer like Edward Dutton, who had the courage to tell the truth about this flawed and troubled man and the knowledge to explain his meaning. In the end, if Jonathan Bowden did not exactly triumph, he endured and perhaps paved the way for a triumph to come. The message of the shaman, after all, is for the tribe, not for himself. Perhaps he even left the best coda for his own life: “[T]he first thing we have to do is to say, ‘I walk towards the tunnel, and I’m on my own, and I’m not afraid. And I have no regrets.’ ” May we all be able to say the same.