Truths (and Half-Truths) Black Conservatives Told Me

Torin Murphy, American Renaissance, June 28, 2024

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Wilfred Reilly, Lies My Liberal Teacher Told Me: Debunking the False Narratives Defining America’s School Curricula, HarperCollins, 2024, 272 pp., $15.00 Kindle Edition, $24.00 Hardcover

Among black conservatives, Professor Wilfred Reilly is unique and uniquely frustrating. To his great credit, he opposes many of America’s worst racial excesses, and in his previous books, he constantly challenged racial oppression myths. He recognizes anti-white prejudice in America, though he sometimes says the solution is for whites to “man up.” He also criticizes LGBT excesses and, more recently, has called for mass deportation of illegal immigrants.

His “black privilege” appears to protect him when he takes controversial positions, even as an academic — which makes it all the more frustrating that he is hostile to white advocacy. In his book Taboo: 10 Facts You Can’t Talk About, he repeatedly scorned any desire for white political autonomy. Elsewhere, he has claimed that race realists attribute group IQ differences only to genes. He also once said, “I don’t think there will be white people in 200 years, and that’s a good thing.” He has, however, said the same thing about blacks, even though they face no equivalent demographic threat.

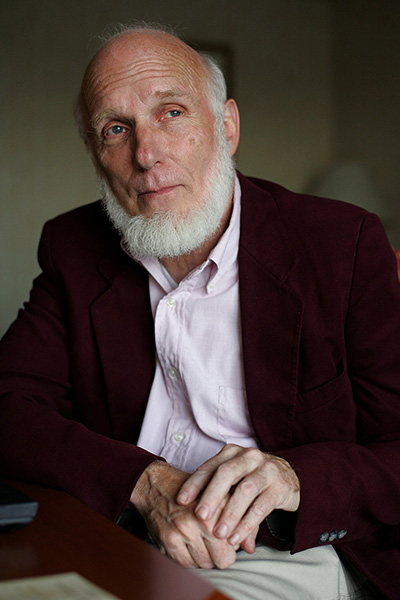

The occasion for those comments was a public debate in 2016 with Jared Taylor on whether racial diversity was a strength for America. The event demonstrates Dr. Reilly’s capacity for controversy and his willingness to “platform” a controversial opponent.

Wilfred Reilly debating Jared Taylor.

Dr. Reilly’s latest book is Lies My Liberal Teacher Told Me: Debunking the False Narratives Defining America’s School Curricula.

The title is a play on James Loewen’s 1995 bestseller, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. Like the original, this is not a comprehensive history, but a broad, discontinuous critique of history-teaching, meant to persuade at least as much as inform.

Contrary to the “claim that American history is taught mostly from the political right — and that it presents our nation as bucolic,” Dr. Reilly points out that most acclaimed, bestselling social science books come from the Left and depict American history as “a virtually unending bloodbath.” (p. xi) Dr. Reilly does not try to restore “bucolic” myths. Instead, he tries to contextualize America’s alleged wrongs in their complicated circumstances and within the sweep of world history. He fights the intellectual fad that “every wrong is uniquely Western and American,” adding that “American history is explained poorly by modern morality but effectively by simple economics and power-dynamics.” (p. 18) Furthermore, “The bad things that ‘we’ did were in most cases done by all humans with the power to do them.” (p. xii) This historical perspective, while preferable to anti-white ones, has limitations, as the book unwittingly demonstrates.

The best aspect of Dr. Reilly’s historical outlook is his disdain for “prey morality,” which he has defined on social media as “an ethical system within which the highest virtue is empathy, and the rational weighting of your interests and those of your in-group over those of strangers and enemies is considered evil.”

Lies effectively conveys some conservative arguments. For example, Dr. Reilly holds in contempt the “Red Scare” mythos, in which “rube politicians abusively harass[ed] innocent teachers and actors, whom they falsely accused of being Communist agents or assets.” (p. 24) In reality, “specific individuals [namely, Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Dalton Trumbo, among others] long thought to be martyrs of a kind were in fact, ‘Communists, Soviet agents, or assets of the KGB — just as McCarthy had suggested.’ ” (p. 30) Lies also touches on the Vietnam War to dispel the myth of evil Americans battling righteous North Vietnamese. The left engages in pro-communist apologia (see Loewen’s hagiographic references to Ho Chi Minh in the original Lies) partly because it sees the war in racial, whites-oppressing-non-whites terms. Though Dr. Reilly doesn’t explore the racial angle, he encourages readers to defend traditional America, albeit from an ideological rather than identitarian perspective.

A separate chapter covers America’s nuclear bombing of Japan, popularly considered unjustifiably evil. Lies explains the logistic and ethical calculations behind the decision, which probably forestalled a costly invasion and prolonged occupation. The book also invokes the horrific bombings of Dresden and other German cities to rule out a purely racial animus behind the nuclear and conventional bombings of Japan. Lies also recounts wartime Japanese atrocities in detail, grisly enough to cure even the most stubborn cases of myopic Japanophilia.

Dr. Reilly, however, does not defend the Japanese exclusion order, routinely used to browbeat white Americans. He includes only the brief lamentation that “Japanese Americans were shamefully incarcerated.” (p. 220) By contrast, A Patriot’s History of the United States deflated the exaggerated injustice of the relocation camps two decades ago, calling them a rational precaution “to protect national security in the face of what most Americans firmly believed was an impending attack.” (p. 608) Lies surrenders needlessly on this issue, noting that some Japanese Americans joined the Japanese army when war broke out. This, together with the largely ignored Ni’ihau incident, vindicates the notion that some Japanese were disloyal.

The highlights of Lies are in its opening and concluding chapters. The first targets the 1619 Project’s thesis that pre-Emancipation America practiced a uniquely cruel form of slavery. Admittedly, what’s noted — the prevalence of slavery throughout history, across cultures; the enslavement of whites in the Barbary slave trade; Europeans as abolishers, not inventors, of slavery; etc. — are points white advocates have been making for years. This is still useful for Lies’ readers, who will, by-and-large, be middle-aged, conventional conservatives. In the conclusion, Dr. Reilly rehashes the best points from Taboo to take on the “Continuous Oppression Narrative.” This mostly consists of using race and crime statistics rightfully to demolish Black Livers Matters’ founding tenets as bizarrely unreal.

Lies includes some unconvincing arguments, even when factual. For example, Dr. Reilly is correct that the Three-Fifths Compromise was not a simple, official devaluation of slaves’ lives. Yet would it really mollify any modern black person to know that it was the result of white politicians haggling over state voting power and taxes? The same goes for the book’s much-expounded-on fact that not all lynching victims were black. (They were “only” about 73 percent.)

Dr. Reilly explains the slightly diverse lynch killings in the historical South as, “a sub-component of terrorism by white radical racists against their opponents in a racially diverse GOP.” (p. 109) This “racially diverse GOP” line is associated with a significant theme in Lies: Democrats are the real racists because they “defended slavery, started the Civil War, opposed Reconstruction, imposed segregation, perpetrated lynchings, and fought against the Civil Rights Acts of the 1950s and 1960s.” (p. 188) Needless to say, Dr. Reilly mentions Republican president Abraham Lincoln frequently, but says nothing about his desire to rid the country of blacks.

Dr. Reilly explains “white flight.” It’s plausible that in addition to black migration, rising incomes and mass car-ownership helped move whites out of cities. He also notes that a rise in crime, “often associated somewhat fairly with big cities and Black [sic] migrants,” (p. 174) was an important factor. Dr. Reilly even cites a study challenging “the canard that crime is a downstream result of poverty. If anything, the reverse seems to be the case: crime causes urban decay, which is then followed by increasing poverty.” (p. 173)

Lies recognizes that the riots of the civil rights era were “largely African American in composition,” (p. 174) and that “the extreme violence damaged the general goals of Blacks.” (p. 175) The Republican Southern strategy — “the intentional use of vague but racialized language . . . to appeal to Southern whites” (p. 185) — is seemingly obnoxious to Dr. Reilly. Rather than defend it, he claims it is a historical myth, though the scholarship of the strategy’s own pioneers contradict this.

Sometimes this book aggrandizes non-whites. It’s true that American Indians were crippled by foreign disease after European settlers arrived. Yet, it’s unnecessary to adopt the mournful interpretation that this robbed Europeans of the chance to interact (or enter more equitable combat) with their “fascinating and advanced cultures.” (p. 71)

Dr. Reilly quotes an obscure edutainment piece to contend that “Hollywood has ‘white-washed the West’ and that, in reality, as many as 25 percent of all cowboys in the Western states during the 1870s and 1880s were of African descent.” (p. 72) I know only of supposition on this point; if Dr. Reilly has strong evidence for it, he should not have listed AllThingsInteresting.com as his source. Dr. Reilly asserts that blacks and Hispanics “were — if anything — overrepresented among cowboys and Indian fighters, in tough male professions where bravery and aggression usually counted for more than skin color did.” (p. 72) This implies that Dr. Reilly believes in biological race differences, but this comes up only when he’s discussing the supposed virility of non-whites. Mainstream conservatives embrace the 25 percent figure both for the sake of blacks as well as themselves. A racially diverse conquest of the continent partially absolves whites of the “sin” of conquering native populations.

Dr. Reilly notes that the white man’s “moment in the African sun [was] surprisingly brief in comparison to that for the post-migration Bantu lords.” (p. 139) He then points to the tiny African nation of Eswatini (former Swaziland) as an example of a “fully independent” nation ruled by restored Bantu royalty. Eswatini gets aid from the United States, the United Nations, the European Union, the World Food Programme, Médecins Sans Frontières, and the Red Cross, etc. Is Eswatinian “independence” really worth thumping one’s chest about?

Likewise, there is a certain vanity in claiming that “for most of post-Roman history, the archetypal ‘colonizer’ was a well-mounted brown man waving a sword.” (p. 137) By this he means the Mongols and the Arabs, who were conquerors rather than colonizers.

Of course, every version of history serves a particular purpose. The textbooks Loewen critiqued in the original Lies (allegedly) promoted a bland civic patriotism meant to educate but never to offend. Loewen in turn promoted the version most apt to drive progressive change in the present, largely by exalting non-whites and shaming whites. Dr. Reilly champions an egalitarian view of history, in which peoples’ triumphs or failures are primarily the product of their environments. This isn’t new; it’s straight out of Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel.

James Loewen. Credit: James19992w, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the original Lies, Loewen quoted writer Anais Nin: “We don’t see things as they are; we see them as we are.” As the racial demographics of America change, the transformation of our national history can only accelerate. Case in point: Dr. Reilly largely represents American right-wing views filtered for their appeal to multiracial conservatism. Hippie-hate and anticommunism come out relatively unscathed, while the Indian Wars or European colonialism suffer unnecessary concessions.

Setting aside any identitarian concerns, even the conservative intent for this book faces steep odds. When Lies My Teacher Told Me came out three decades ago, it didn’t need to revolutionize academia, only expedite the trickle-down of the elite university canon to basic education. It succeeded. Now, Lies My Liberal Teacher Told Me can’t challenge the Left’s near-monopoly on education without elite realignment. However, its plain-written style, broad palatability and brevity, as well as the conservative need for black affirmation, do guarantee some popularity. Let us hope this book helps readers defend American history, which is, regardless of who recognizes it, the story of a great white nation.