Why Electing Blacks Is Disaster for Whites

Joseph Kay, American Renaissance, April 4, 2024

Credit: Marion S. Trikosko

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Access to the ballot box has always been one of the main goals of the civil rights movement. The 1965 Voting Rights Act was a great victory. It outlawed literacy tests and gave the national government oversight over elections in places where less than 50 percent of the non-white population was registered to vote. Subsequent measures such as banning the poll tax and manipulating election district boundaries further extended black electoral clout.

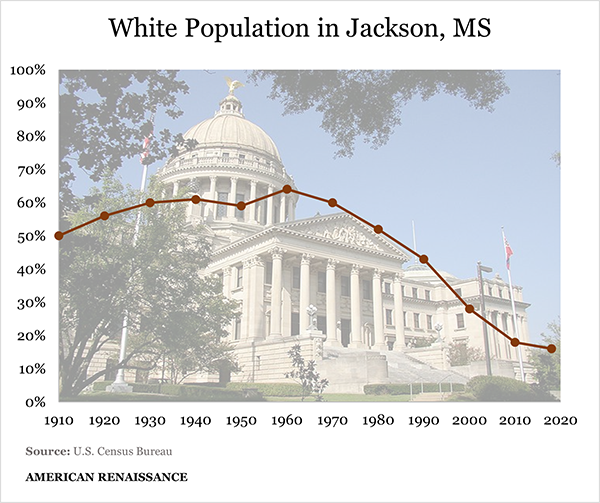

Nevertheless, these many accomplishments have not improved the lot of ordinary blacks. The very opposite is true in black-dominated cities such as East St. Louis, IL, Gary, IN, Jackson, MS, Camden, NY, among others. Nor, at the national level, has increased black voting led to better educational outcomes, improved health, and less crime. Nor has it reduced illegitimacy or drug addiction.

Why, then, do blacks persist in pursuing this electoral strategy? Why do they still complain of “voter suppression”? It’s a paradox: Blacks demand ever more election access while this access seems to improve nothing for them. And why is that?

The conventional explanation is that both Democrats and Republicans have pushed voting despite its dystopian impact, but for different reasons. For Republicans, increased black voting makes it easier to draw “majority-minority” districts that concentrate blacks while “whitening” adjacent areas to elect more Republicans. Racial gerrymandering means more black officials, but also more elected Republicans.

For Democrats, it’s all about electing other Democrats. Jackson, MS, is a disaster, but come election day, there will be no shortage of Democrat votes, their number no doubt augmented by lax voter and ballot security.

There is another explanation that is almost never admitted publicly: these dystopian transformations are inevitable. After all, there is no necessary relationship between the mobilization of votes and urban dystopia. Everything depends on who is being mobilized, and outcomes would be radically different if political parties were boosting turnout among Asians, for example. The essential characteristics of black rule — corruption, crime, terrible schools, incompetent administration, deterioration of infrastructure, and all the rest reflect the preferences of blacks themselves. Elections just give people what they want.

A black candidate for mayor does not run on a platform of closing the local Walmart and replacing it with a higher-priced Indian-owned convenience stores. Nor do black parents vote out the current white school board to promote schoolyard violence. If surveyed, blacks want the opposite; they love their Walmart and want the best education for their children.

What causes this discrepancy between what blacks say they want and what happens under black rule? First, all preferences exist in a hierarchy that reflects the costs of each preference. Blacks may want exactly what whites want, but they differ in how they rank these choices and what they are willing to pay for them. These differences are what culture is all about; humans broadly want the same things, but there are sharp differences in how to pursue the things they want. This does not appear in answers to simple poll questions, such as “What do you want?”

A black resident of Selma might love to shop at Walmart because of its low prices and broad selection but only if Walmart does not prosecute shoplifters. His white neighbor, by contrast, sees no personal cost to Walmart’s strict shoplifting policy. Similarly, black parents might want a first-rate education for their children but not if this means strict discipline and coercion. Policy preferences are not stand-alone entities. Life is about trade-offs.

Different hierarchies are particularly evident in combatting crime. While everyone, regardless of race, is anti-crime, many blacks are anti-crime only if eliminating crime does not involve being stopped and frisked by the police, being pulled over for minor automobile infractions, having to undergo criminal-record checks for employment, and similar hassles that reduce crime. Whites do not enjoy police encounters, but accept them as necessary for public safety. In short, blacks often want the benefits of anti-crime measures at impossibly low costs.

Thousands of demonstrators march down Fifth Avenue in New York for a silent march protesting the NYPD policy of stop and frisk. (Credit Image: © Richard B. Levine/Levine Roberts via ZUMA Press)

In addition, blacks undoubtedly feel that government efforts to “cure” their alleged pathologies are less about kindness than disrespect for their habits. Recall the outrage when Daniel Patrick Moynihan called for a national effort “to fix” the black family. But imagine the white reaction if a distinguished black academic had issued a report demonstrating that the white obsession with monogamy caused mental illness. Whites would be enraged, just as blacks were when told their family life was “pathological.” Here is one way to think of it: Both whites and blacks want to prosper, but blacks are unwilling to pay the costs of prosperity if that requires abandoning habits that destabilize families.

Conservatives are thus frequently misled by surveys showing that blacks and whites want the same things. At one level this is true, but not everyone ranks preferences equally and calculates costs identically. A “good job” means a high salary, but for some, this benefit is outweighed by the need to be punctual, follow rules, take orders, do boring things, etc. For such people, vocational programs promising “good jobs” won’t be appealing unless all the negative aspects of working can be eliminated, which is impossible.

Imagine that the federal government decided to build a big Section 8 housing project in Stockbridge, MA (95.2 percent white, 1.23 percent black) and filled it with poor blacks from Roxbury, MA. Stockbridge is a splendid, artsy town with quaint stores, clean streets, no crime, and great schools. Potential black residents would be thrilled to relocate.

The Norman Rockwell Museum, attracts 122,000 visitors a year in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. (Credit Image: © Ellen Creager/TNS via ZUMA Press Wire)

But the results of relocation are predictable. In a few months, racial tensions would surface, and many blacks would complain of being harassed by the local police for littering or drinking in public or openly selling marijuana. Shopkeepers would notice more thievery and schoolteachers would complain about unruly black students. A white exodus would begin and there would be more Section 8 tenants from Roxbury.

“Faces of Dudley” mural in Roxbury, Massachusetts, featuring Malcolm X and other icons from Roxbury. (Credit Image: © Sergi Reboredo/ZUMA Press Wire)

Blacks would start voting, denouncing over-policing, “racist” school discipline, and other toxic “whiteness.” Blacks, often with white liberal support, would run for the city council and school board. Any effort to curb black voting by, for example, locating polling sites far from black areas, would invite costly DOJ oversight. As the town’s demography shifted, once-white picturesque Stockbridge would begin to resemble the slums of Trenton, NJ.

Blacks are not unique in using elections to create environments that reflect preferences that contrast sharply with American society more generally. The small town of Kiryas Joel in upstate New York, has a population of 20,000, almost entirely ultra-orthodox Jews from the Satmar sect. This group originally lived in Brooklyn, NY, then many moved upstate to Monroe, NY. In 2018, they exercised their political influence to start an entirely new town with its own officials, including a town court. Though there are regular elections, everything is controlled by religious leaders, making it a de facto theocracy. Very few residents speak English at home, and it has the highest poverty rate of any town in America — but virtually no crime. During the pandemic, the school district also got $94,000 per student in federal aid, though learning is devoted almost entirely to study of the Torah and Talmud.

What many Americans think of as “dysfunctional” black cities is consistent with the world-wide decolonization that began in the late 1950s. Millions of Africans and Asians ousted their colonial rulers in favor of self-rule. Though locals might have had qualms about replacing the British or the Dutch, the desire to be ruled by people like themselves was stronger. Blacks in Gary, IN, Jackson, MS, and similar cities may be thinking the same way: Yes, the economy may collapse, but that is less important than cultural autonomy.

Building a community around a single culture — black, Appalachian, or Orthodox Jewish — is like a lab experiment. Outcomes reflect the group, and this is equally true in Stockbridge, MA, and Jackson, MS. I argue that these outcomes better reflect what the group really wants, and are far more accurate than the results of preference polling (“Do you want good schools?”).

Understanding what people really want has major implications for public policy. First, it avoids the cliché, “We are all the same and all want the same things” invariably trotted out to justify expensive government expansion into every corner of life. Yes, all people want less crime, but at what cost? Voters get what they want. Actions speak loader than words.

Sharp group differences in preference ordering and tolerance of costs suggest there should be political separation. To be sure, many communities have divergent voter preferences and can reach compromises, but this is not inherent to democracy. Differences may be intractable. Everything depends on the details, and it is foolish to wonder, “Why can’t we all get along?” Sometimes, the best solution to domestic strife is divorce.

Officials in Stockbridge, MA, would be unable to close the gap between poor blacks and middle-class Yankee whites no matter how much “diversity training” they got. Stockbridge storekeepers depend on customer honesty, while black newcomers might see this as an invitation to theft. Differences in the value of public cleanliness, noise levels, or whether sidewalks should be used for peddling trinkets — there are dozens of other differences in preferences that can’t be eliminated. If Stockbridge decided to allow public intoxication, drag racing on Main Street, and open-air drug markets, Stockbridge would no longer be Stockbridge, and residents would leave and create a new Stockbridge somewhere else. Ditto if Jackson, MS, suddenly enforced public-order laws or expelled unruly grade-school students. Jackson officials enforcing these policies would be turned out of office.

Harsh limits constrain social engineering to “improve” the lives of those who prefer to live in certain ways, and this is a reality few “reformers” acknowledge. If “dystopia” is so horrible, why do locals vote for it? Regardless of what do-gooders insist, and all the billions they spend, some people refuse “improvement.” Transforming East St. Louis into the next Stockbridge would be a true disaster for today’s East St. Louis residents. It would be much easier to turn Stockbridge into East St. Louis.