Tolkien: The Homer of the Anglosphere

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, December 15, 2023

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

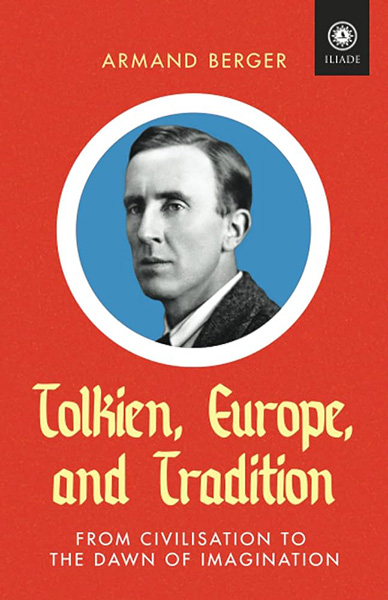

Berger, Armand, Tolkien, Europe, and Tradition: From Civilisation to the Dawn of Imagination, Arktos Media Ltd, 2022, 66 pp.

A people without roots is a people without a future, perhaps not a people at all. The trend of “white erasure” in historical films, art, and even documentaries suggests that our rulers know this and are deliberately writing whites out of our own history. This includes even myths and legends. While non-white stories belong to the peoples who spawned them, European stories are either deliberately subverted (“re-imagined”) or become universal tales with equal meaning to everyone. “Cultural appropriation” is a one-way street.

J.R.R. Tolkien and his work is an important battleground, as The Lord of the Rings and his other books win new audiences every generation. Undoubtedly, stories that encourage people to identify with and fight for their people and culture subvert orthodoxy, so, finding anything more than entertainment is dangerous. When Georgia Meloni became Italian prime minister, the New York Times warned that she and other activists see The Lord of the Rings “as not just a series of novels but a sacred text.”

The film trilogy is a favorite and an inspiration for many white advocates. We are lucky that it was made before the era of “race-swapped” casts, and filmmakers who seem to hate their source material. The Southern Poverty Law Center complained that the movie’s heroes were “manly men who are whiter than white” with a “heavenly aura of all that is Eurocentric and good.” The late Sam Francis took note:

[The SPLC] thinks “Lord of the Rings” is bad because it reflects white racial and patriarchal stereotypes, and as a matter of fact, it probably does.

That’s because those “stereotypes” are integral to the complex tale of civilizational struggle that Tolkien was telling, a tale that thoroughly modern multiculturalists would prefer had never seen cold print because it also happens to be the tale of our real civilization.

It’s the tale of our real civilization because the kings, warriors, and heroes who led us have always been manly men who really were whiter than white, and that just might have had something to do with why they won the struggle against their civilization’s enemies — medieval and modern — at all.

Francis concluded that what the SPLC opposed was any “positive portrayal of white people.” At that time (2004), this was prescient. Today, it is taken for granted that films and television smear whites. What used to be a white hero becomes a non-white woman. It is so common it has become a cliché.

The most recent Rings of Power series on Amazon was typical. Amazon spent more than a billion dollars to make the most expensive television series of all time, and it hit the classic tropes of “modern” television.

Naturally, there was a clumsy attempt to “diversify” everything, with non-whites in prominent roles. Characters were also changed to fit “modern” ideas of “strength.” In Tolkien, the ethereal Galadriel is an elf whose beauty is so great that it is threatening and dangerous. When she toys with taking the One Ring, she promises that “all shall love me and despair.” In Rings of Power, she is an arrogant, hysterical girlboss who uses brute force to dispatch opponents, even while making stupid decisions that lead to disaster. The one strong and charismatic white man turns out to be the bad guy.

Critics and fans delighted in tearing up the series. Despite its huge cost and media attempts to prop up the affirmative-action production, it got disappointing ratings and had little impact.

One of its most interesting aspects was overlooked. The television series lingers over the fall of Númenor, the greatest civilization of man. A beautiful city with traditional architecture (made of white marble that drives journalists and academics crazy), the show stripped it of its mystique to fit its ham-handed political messages. The city is full of xenophobes worried about “elf-lovers” taking their jobs. However, Númenor is an important symbolic setting for Tolkien, about a people that is deceived into abandoning true religion for the worship of temporal power. In his letters, Tolkien linked this story of a collapsed civilization reclaimed by the sea to Atlantis. He admitted he was haunted by “the legend or myth or dim memory of some ancient history.”

The question of whether Tolkien’s writing was “for” Westerners is fiercely debated. He famously refused to work with a publishing house in National Socialist Germany after it asked for proof of Aryan lineage. In a letter to his son, Tolkien also called Adolf Hitler an “ignoramus” and accused him of “perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe, which I have ever loved, and tried to present in its true light.” Yet claiming Tolkien for the modern, anti-white Left is like claiming that the anti-Hitler views of Churchill or de Gaulle make them anti-racists. Certainly, Tolkien would have rejected the idea that only certain people are allowed to read or interpret certain stories, but would also have scorned the idea that whites — and whites alone — have no culture to be proud of.

Tolkien deeply loved the literature and mythology of Europe, particularly that of the Anglo-Saxons, and was professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. While the same endowed chair still exists, the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists has changed its name to avoid accusations of racism, and Cambridge is crusading against the very concept of Anglo-Saxons. Anyone who, like Tolkien, admitted to a particular love for “that noble northern spirit” would hardly survive in modern academia. However, his work has been grandfathered in and can be only subverted, not expunged. Tolkien’s work is one of few relatively recent cultural creations that derives entirely from European mythology and even now, despite attempts at subversion and even perversion, retains its beauty. Young readers, especially, should learn why this work has such an impact. Armand Berger’s Tolkien, Europe, and Tradition is up to the task.

Everyone knows Tolkien was obsessed with languages (and famously wrote poems and songs for his races in Middle Earth languages he invented), but Mr. Berger takes us further. Tolkien was especially interested in Gothic, even to the point of inventing new words to fill in the gaps and then writing poetry in “neo-Gothic.” Tolkien invented 40 or so languages that “draw their inspiration from our ancient European languages.”

His stories were also mined from similarly rich sources. Mr. Berger argues that they derive from three traditions of Northwest Europe — Celtic, Finnish, and German-Scandinavian — with the latter having the greatest influence. In some ways, he reinvented fantasy by returning to the source. What had survived as “elves” in English literature were fairy-like creatures, but Tolkien gave them back their dignity. “The elves may have been linked to the veneration of ancestors,” says Mr. Berger, “as well as to a cult of fertility and death in the Scandinavian tradition.” In Middle-Earth they are gifted with magic, beauty, immortality, and artistic talent. Tolkien himself said that the Völsung Cycle, perhaps the best known of the Nordic sagas, was “inferior to Homer in most respects,” but had “a certain veracity that excels it” and also handled love more effectively. The saga’s story of a dragon guarding an accursed treasure is familiar to anyone who has read The Hobbit.

Mr. Berger cites what he claims was Tolkien’s goal: “To be fully immersed in one’s culture, to the point that an unstoppable furor spreads within one’s self.” He adds that this was “a powerful impetus that seeks to give new breath to a tradition that is fragmented, if not already lost. Thus was Tolkien’s ambitious plan to create a ‘mythology for England’.” This is certainly not something most scholars now want to admit was his mission. In 1951, Tolkien said he was “grieved by the poverty of my own beloved country,” that its stories were bound up in “legends of other lands.”

Tolkien famously rewrote myths that he liked, including some from the Arthurian tradition and the Norse sagas, but also the Finnish Story of Kullervo. Elements of these myths are so common in The Lord of the Rings and other books that they become part of the structure of the story — a new expression of ancient ideas and motifs. “By doing it this way, Tolkien cast an extremely bright light on the slopes of our creative imagination and ultimately on the deepest structures of our culture,” writes Mr. Berger. “Myth . . . survives in fragments and occasionally manages to mix with Christian feelings that impart to it a new vitality just as it imparts to them an even more dramatic, unknown force.” Tolkien thus presents “to modern man a vast fresco of ancient times through remodeled traditions.”

These “remodeled traditions” are not subverted traditions. Mr. Berger identifies the “essence of the Anglo-Saxon epic tradition” as “loyalty to a valiant person whose destiny one shares.” Heroic acceptance of death with honor is typical of the Northern European warrior, and Mr. Berger links this to the gallant King Théoden of Rohan. Mr. Berger likens Aragorn (the model Tolkien king) to Amleth, the Danish prince who inspired Hamlet. Aragorn is the more heroic side of this character, and ultimately recovers his throne after exile. The hobbits, the simple rural folk who unexpectedly achieve heroism, symbolize to Mr. Berger nothing less than a new form of mighty deeds based on traditional elements, with a people “who do not belong to history” taking a valued place. He compares them to the unknown British soldiers who served in The Great War, in which Tolkien also fought.

Depiction of Aragorn. Credit: Ashenhard via DeviantArt, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DEED

The Lord of The Rings won a great following among anti-Establishment hippy “greens” during the 1960s. “In all my worlds, I take the part of trees as against all their enemies,” wrote Tolkien in 1972. Mr. Berger writes that “this effective way of working in the world of trees hearkens back to the purest Western tradition.” He continues: “[It is] that of the forest as a special place for encounters with danger, whether with wrongdoers, with fabulous creatures, or with the vegetation. In mediaeval literature, it is accepted that the forest world is, if not neutral, somewhat hostile to man.” It is in the forests that Northern European man most knew himself. Tolkien even fantasized about a Ragnarök burning “all the slums and gas-workers, and shabby garages.”

Mr. Berger’s final chapter defining Tolkien’s work as “a defense of European civilization” will appeal most to white advocates. That this should be controversial is a sign of the depravity of our times. It is entirely proper that a people should see itself in works that draw on the deepest veins of its culture and history. “Tradition is a matter of choice: either to pass it on, to ensure its succession, and to keep the heritage alive, or to let it disappear in the face of nihilism,” Mr. Berger writes. “If there is no longer any tradition, we renounce who we are and we leave the field free to all the excesses that the world generates.” He argues that “the enemy will not triumph as long as tradition remains, as long as there are people in the world capable of holding up the full weight of a legacy.” Tolkien’s work offers a choice: either the fall of Númenor into decadence and destruction or the counter-example of Gondor, saved by the return of the king and a cavalry charge reminiscent of the relief of the Siege of Vienna.

Mr. Berger goes so far as to call Tolkien’s work a “new founding text for our identity” that could allow us “to maintain the sacred fire.” It isn’t quite that, but it could be close. It is the most approachable work to start young people on a lifelong journey of understanding themselves as part of a great people. However, it must not stop there. It should inspire them to understand more fully where they come from, and how the most ancient stories inspired J.R.R. Tolkien. “It is up to European man to know his modern mythology and the heroes related to it,” Mr. Berger writes. The point is not just to know them but to become the generation that will become the source of mythology in our future.