Honoring Our Ancestors

John Hill, American Renaissance, October 13, 2023

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

My name is John Hill. I am the closest living collateral descendant of Lieutenant General A. P. Hill, CSA. I personally exhumed General Hill’s remains on December 13, 2022, in Richmond, Virginia, and was a pallbearer at his reinterment in Culpeper, Virginia, the following January. I am now also his National Guardian, a designation from the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and as such I tend his gravesite and work to keep his memory alive.

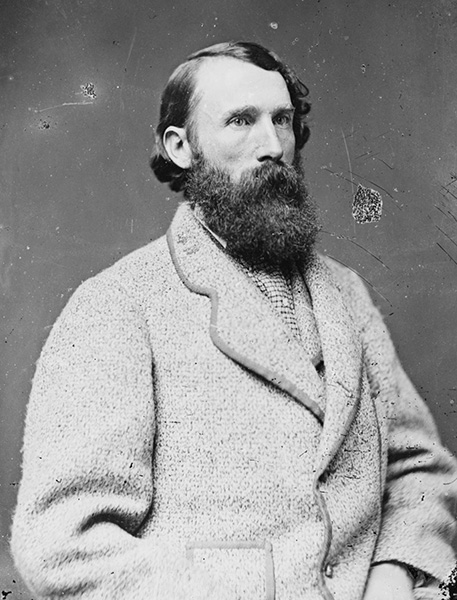

General Ambrose Powell Hill was, according to historian Shelby Foote, “a hard fighter, with a highstrung intensity and a great fondness for the offensive.” A native Virginian, he was graduated from West Point in the class of 1847. He fought in the Mexican-American War and Seminole Wars as a career Army officer before joining the Army of Northern Virginia after secession.

Early in the war, “Little Powell” distinguished himself under the command of Stonewall Jackson until Jackson’s death in May 1863. At Sharpsburg, General Hill saved Lee from defeat — and caused Union General McClellan’s dismissal — with his timely arrival at Antietam Creek. After Stonewall’s death, he was promoted to lieutenant general and commanded the Third Corps of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which he led in the summer Gettysburg campaign and the fall campaigns of 1863. He was killed late in the war at the Third Battle of Petersburg.

In spite of his accomplishments, General Hill has been called, in the words of one biographer, “Lee’s Forgotten General.” Yet, Lee never forgot. As Lee lay dying, years after the war, among his last words were, “Tell A. P. Hill he must come up.”

For more information about General Hill’s life and military career, see my website.

A. P. Hill

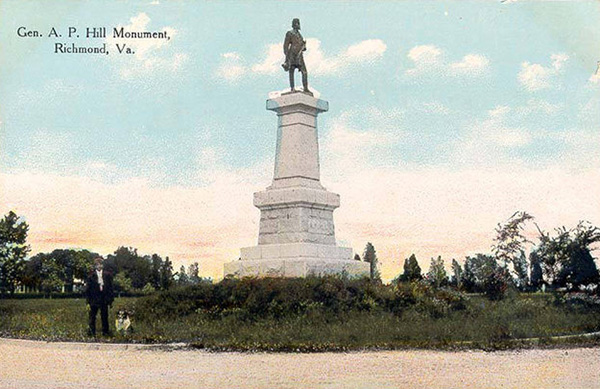

I became involved in the conflict over General Hill’s grave and monument in May 2021 when, on hearing of the city of Richmond’s plans to tear down that monument, I emailed city officials. I told them that it was not just a monument, that it was also a headstone over a grave, and that I would take whatever actions necessary to stop its removal. They forwarded my email to the Richmond City Council, and I was contacted by a representative of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who was already in communication with the city. This SCV member already had a lawyer involved in the case, and he became my lawyer as well.

On September 29, 2022, I drove eight hours from my home in Ohio to Richmond to appear at the first in-person court session in the Richmond Circuit Court courtroom of Judge David Eugene Cheek Sr. On the stand, I presented documentation establishing my lineage to General Hill, explaining that he left no direct descendants and that I am his closest cousin. Next, I tried to explain to Judge Cheek that the monument was a headstone with my family name on it and that I did not think anyone in the courtroom would want to see a family member’s grave desecrated. At that point, my own lawyer interrupted me by leaning forward into his mic and saying “No!”

I almost walked out of the courtroom at that point, but I stayed for the General’s sake. Saying he would have a decision within 30 days, Judge Cheek soon adjourned the court. Both lawyers shook hands and congratulated each other, which I found suspicious. Afterward, my lawyer excused his interruption by saying “a good lawyer always knows what his client is going to say.” Good lawyer or not, I believe I would have been better off representing myself.

One of the key questions the judge needed to answer was whether the site where my ancestor was interred was legally a “cemetery,” which would make it much more difficult legally for the city to relocate. On our side, we had VA Code 54.1-2310, which states that a cemetery is “any land or structure used or intended to be used for the interment of human remains.” That seemed clear enough.

However, the city ignored VA Code 54.1-2310 and invoked another provision in the Virginia Code — VA Code 15.2-1812 — which deals with war veterans’ memorials, but not graves. Memorials have fewer restrictions on removal. In addition, a city ordinance passed in August 2020 had explicitly authorized the removal of all Confederate statues on city-owned property. My ancestor’s monument was the last statue remaining, and the trend was going strongly against us. Judge Cheek, a black man, seemed inclined to support sending our Confederate monuments to the black history museum to be melted down. I sensed the outcome before the decision was revealed.

On October 25, the judge announced his decision. The city’s petition was granted. In the judge’s opinion, the site was a military memorial, not a grave, and based on the 2020 ordinance, he ordered the removal of General Hill’s monument and the relocation of his remains.

Eventually, my lawyer filed an appeal, but only after I informed him in a group email saying that I had not been contacted and would take matters into my own hands. On December 8, our Motion to Stay was denied, and the monument was ordered to be taken down on Monday, December 12.

I again drove the eight hours to Richmond, arriving around 5:30 Monday morning. Crews were to begin disassembling the monument about 9:00, and in the meantime I did several radio interviews. Once the work was underway, I gained access to the work zone to make sure the workers didn’t damage the monument. They were down to the final stones above the grave when they finished on the first day. Work continued on December 13, and they got down to the three large “capstones” over his grave.

The first capstone was removed by crane, and I saw A.P. Hill’s remains. All that was left of General Hill were his skull, rib bones, leg bones, and some other small bones. The casket had completely deteriorated, so I asked the city workers for a tarp to hide the remains from the news photographers. I also asked the workers to park their vehicles between me and the news media to block their view, and I waved away a man trying to take photos with a drone.

Once I felt that my ancestor’s remains were safe from the photographers, I let the work go on. The sun came out when the third and final capstone came off. I became teary eyed as I placed the tarp over the remains. I tried not to cry in front of everyone and climbed down into the grave. Along with a funeral home director, I started placing the remains into a body bag.

I had never thought I would be handling the remains of a Confederate general. The grave was lined with stone, and at the bottom were a couple of inches of damp soil that contained his DNA and various bone fragments, which we put into the body bag as well. Within the dirt inside his grave, I found three pieces of his uniform and three buttons. I also found two metallic items that appeared to be pieces of keys.

After the remains were sealed in the body bag, someone asked me if I would like an American Flag to drape over them. I said no, that is the flag that killed him. I wanted the Unreconstructed Virginia Flag.

While all this was happening, I was receiving threats from blacks standing behind the police tape. I confronted them, but I do not want to ruin this article by writing more about them.

I got little support that day. No one came from the headquarters of the SCV or of any other Southern heritage organization. I did receive some much-appreciated support from behind the police tape from three members of the Fourth Platoon of the Mechanized Cavalry, a group of motorcycle enthusiasts affiliated with the SCV. I will be forever grateful to Anthony, Derek, and Bubba, who remain my friends today.

Many people seem too afraid to speak for or stand up for their heritage. But as for me, I would have died for A. P. Hill on that day. Later, I was his pallbearer at his reinterment at Fairview Cemetery in Culpeper, where I first met Jared Taylor and shook his hand.

Jared Taylor and John Hill.

Members of the Mechanized Cavalry at the reinterment of A. P. Hill.

On March 14, 2023, the SCV named me General Hill’s National Guardian. As such, I tend his gravesite and travel the country giving presentations on his life and achievements. I have started the A.P. Hill Legacy Foundation to raise funds to erect a new monument for him. I welcome any donations from American Renaissance readers.

As for the monument removed by the city of Richmond, it is being stored, along with the other Confederate monuments that have been taken down, at a waste water treatment plant in the city. There appears to be little likelihood they can be retrieved. A descendant of J. E. B. Stuart tried to buy the Stuart monument, but his offer was not even considered. We might never get the original Hill monument back, but if we do, we will have two, because the new one will be erected no matter what!

In closing, I have dedicated my life to the memory of Ambrose Powell Hill, and my goal is to make him a household name like Lee and Jackson. Attempts like those of the city of Richmond to erase our history and heritage will not succeed. I will make sure that he will never again be Lee’s Forgotten General.