Rufo’s Counter-Revolution and Its Limits

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, July 28, 2023

Credit: rufo.substack.com

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Christopher Rufo, America’s Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything, Broadside Books, 2023, 352 pp.

America’s Cultural Revolution is essential reading. No other book so quickly and comprehensively explains the specific figures and ideologies responsible for the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) monster that has consumed American education, law, and culture. Christopher Rufo is probably the most important activist today, building a movement to confront DEI standards directly, pushing conservatives into winnable elections for bodies like school boards, and making the American Right comfortable with the language of “counter-revolution” (his term) that will be needed to restore the American republic.

Yet, though Mr. Rufo is effective, he doesn’t have much new to offer white advocates. Married to an Asian woman and with interracial kids, he is not a white advocate and doesn’t pretend to be. He isn’t one of us and isn’t speaking to us. He’s a true believer in the “colorblind” meritocratic ideal and recognizes the main threat to it today comes from the Left. Still, if we had more people like him, we wouldn’t have many of the race problems we currently do.

“If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?” asks the villain in No Country for Old Men. One could ask the same about Mr. Rufo’s “counter-revolution.” One major flaw with his book is that despite his careful analysis of the leading figures who brought us DEI, he doesn’t explain why they were so easily able to capture academia, win media support, and enjoy sinecures in establishment institutions despite supporting (or being directly involved in) revolutionary violence. The rot was deep-seated and present decades ago, not some sudden innovation. Colorblind conservatives — let alone white advocates — won’t be able to accomplish a “long march through the institutions” so easily. This is an introductory work that gives us the situation and the problem. It’s not a map that leads to victory.

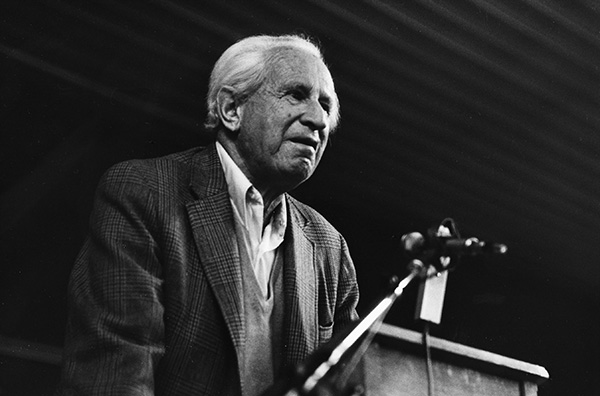

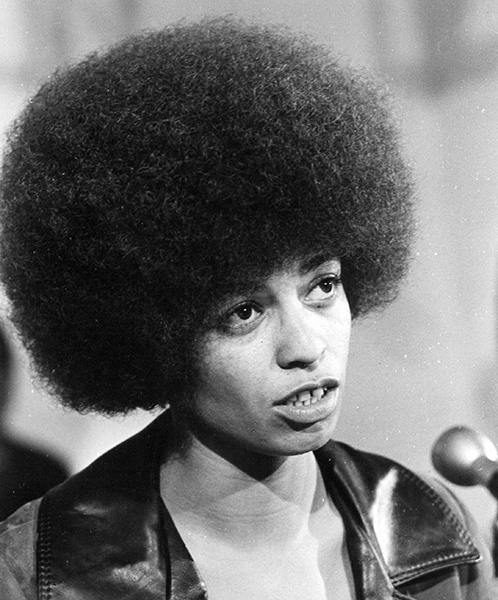

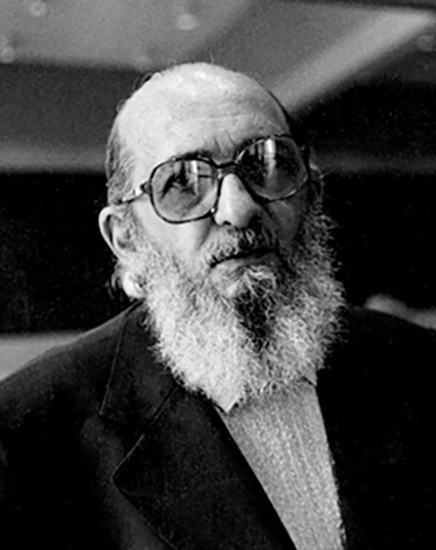

America’s Cultural Revolution is structured like a collective biography, with a key thinker linked to each major concept. Herbert Marcuse — champion of the Frankfurt School and arguably the most influential thinker of the New Left — is linked to “revolution.” Communist agitator Angela Davis is linked to “race”; while Paulo Freire, who popularized critical pedagogy, is linked to “education”; and Derrick Bell is linked to “power.”

Through these four thinkers, we understand what drives the modern Left; not just what they say, but what truly motivates them. It’s shocking, though not surprising for white advocates, to be reminded that these supposedly innovative thinkers were credulous fools when it came to Communism, and figures like Davis and Freire were embarrassingly naïve (or breathtakingly cynical) about the brutal reality of life in the Communist bloc. The extent to which these figures have conquered the commanding heights of our culture raises the question of whether America really won the Cold War.

Mr. Rufo’s book is important because he makes it hard for conservatives, even the most naïve, to pretend not to understand where power lies today. He writes: “Although the official political structures have not changed — there is still a president, a legislature, and a judiciary — the entire intellectual substructure has shifted. The institutions imposed a revolution from above, effectuating a wholesale moral reversal and implementing a new layer of ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ across the entire society. Nobody voted for this change; it simply materialized from within.” (4)

This is a welcome counter to Conservatism Inc. thinkers earnestly writing about constitutional checks and balances as though such things still matter to those who rule us.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway of the book is that DEI advocates really don’t share common goals with normal people. They are not simply misguided. They cultivate and use resentment as a weapon. Solving poverty or alleviating suffering were never goals in themselves, because without alienated, angry populations, there would be no revolutionary class to be used to overthrow the power structure and impose Communism. Marcuse is the most important thinker here. His support of Communism was not primarily economic, but spiritual, biological, and even sexual. He argued that in a liberated society, “‘rebellion would then [take] root in the very nature, the “biology” of the individual’ and unleash a pure freedom beyond necessity, exploitation, and violence.” (11)

Herbert Marcuse (Credit Image: © Ulf Andersen/Aurimages via ZUMA Press)

Revolution failed because American media power convinced would-be revolutionaries to accept their subjugation. The solution is to hollow out traditional institutions, encourage rebellion, and take over these “great chains of information and indoctrination.” Critical theory is a powerful weapon because it gives the intelligent and ambitious a moral reason to subvert and take over any institution they enter and turn it into a vehicle for enforcing ideological agreement. What’s more, even when the advocates of critical theories enjoy power, they can continue to frame their actions as rebellion or fighting the elite, using language about being an “ally” to justify a frankly brutal program of repression.

The extent of the leftist takeover can’t be exaggerated. The university has been remade in Marcuse’s image. “The critical theorists and their allies in the bureaucracy have turned the university into what Marcuse called the ‘initial revolutionary institution,’ which, Marcuse believed, could serve as a template for ‘collective ownership’ and finally make possible ‘the creation of a reality in accordance with the new sensitivity and the new consciousness.’” (50)

The press too has fallen. Mr. Rufo writes that young New York Times journalists, influenced by critical theory, “waged a ‘generational battle’ against existing leadership at the paper and the writers’ union, eschewing traditional labor concerns in favor of agitating for the implementation of diversity programs and left-wing ideological priorities.” (55) Mr. Rufo cites Zach Goldberg’s research on the way that “the vocabulary of the critical theories rapidly conquered the paper’s linguistic universe,” with mentions of racism and white privilege skyrocketing between 2011 and 2019, leading to a major transformation in American politics.

Mr. Rufo says that today’s DEI activists are utterly dependent on the state and part of the system itself. Regarding the system he was assailing in the early 1960s, “Marcuse had once lamented the ‘language of total administration’ that moved in ‘synonyms and tautologies’ and made itself ‘immune against contradiction,’” he writes. “A few decades later, his disciples were wielding that technique in their favor. By combining the academic program of the critical theories with the bureaucratic program of diversity training, left-wing activists discovered the formula for expanding their power over the university as a whole.” (47)

Though he doesn’t discuss it, a rightist critical theory is sorely needed. Marcuse’s ends may have been perverse, but his theories about the means of cultural production have been proven correct by the success of his own movement. Public opinion can be dictated. Public consciousness and the most fundamental moral premises of a society can be changed simply by changing personnel at universities, newspapers, and other important bodies. The Left is correct to pursue “cancel culture.” Conservatives and old-fashioned liberals failed to keep out radicals, allowing institutions’ very purpose to be inverted and dedicated to their own destruction.

Mr. Rufo doesn’t dwell on it, but the conflation of whiteness with oppression led to bloodthirsty fantasies among many of those who took critical theory to its most extreme conclusions. The left-wing terrorist group the Weatherman Underground “engaged in macabre thought experiments and contemplated the question of whether it was ‘the duty of every good revolutionary to kill all newborn white babies,’ who would otherwise ‘grow up to be part of an oppressive racial establishment.’” (30) One FBI informant reported that the group’s leadership was already pondering that “they would have to eliminate 25 million people in these re-education centers,” quite explicitly meaning killing people. (30)

While Herbert Marcuse saw non-whites as a potential revolutionary class, he was still pursuing a broadly universalist end that, in theory, would “liberate” all people. The other thinkers Mr. Rufo profiles were far more focused on race. One of Marcuse’s students, Angela Davis, became a pop culture icon because she was a Communist who defended violence in support of revolutionary causes. A jury acquitted her of involvement in an attack on a courthouse in 1970 that killed four people. The reasons seem drearily familiar: jurors wanted to alleviate racial guilt. Mr. Rufo writes, “One juror flashed the Black Power salute to the audience outside the courtroom and told reporters: ‘I did it because I wanted to show I felt an identity with the oppressed people in the crowd. All through the trial, they thought we were just a white, middle-class jury. I wanted to express my sympathy with their struggle.’ Later that evening, a majority of the jurors attended a rock-and-roll festival in celebration of acquittal.”

Angela Davis (Credit Image: © Globe Photos/ZUMA Wire)

Angela Davis’s career before and after the acquittal was spent mostly in academia, where she traveled comfortably from job to job despite her violent rhetoric and the occasional pushback from figures like California governor Ronald Reagan. “Davis was one of the first to argue that the fight against oppression must include the fight against racism, patriarchy, and capitalism,” Mr. Rufo writes. (102)

The Combahee River Collective Statement — a document issued by a black lesbian group in 1970 — “operationalized Davis’s unified theory of oppression” and “gave birth to the term ‘identity politics.’” While male-dominated revolutionary groups like the Black Panthers devolved into pointless violence and meaningless deaths, Davis and activists like her “created a uniquely feminine program that marshalled identity, emotion, trauma, and psychological manipulation in service of their political objectives,” recasting “left-wing politics as an identity-based, therapeutic pursuit.” (103)

“There is trauma related to being outdoors,” the founder of an organization working to provide safe spaces for Black people to enjoy outdoor activities says.

“There’s a lot of healing that we as a Black community must do.” https://t.co/pGFNa6gJQO

— NBC News (@NBCNews) July 26, 2023

Davis also wanted to “demolish the founding myths of the United States, which, she believed, would create a predicate for subverting the institutions that maintained the system of racial domination.” (104) Eldridge Cleaver, the black author of Soul on Ice (1968) who infamously defended the rape of white women as a revolutionary act, argued in his essay “The White Race and Its Heroes” that undermining whites’ cultural confidence was a necessary part of this subversion. Mr. Rufo quotes: “The new generations of whites, appalled by the sanguine and despicable record carved over the face of the globe by their race in the last five hundred years, are rejecting the panoply of white heroes, whose heroism consisted in erecting the inglorious edifice of colonialism and imperialism; heroes whose careers rested on a system of foreign and domestic exploitation, rooted in the myth of white supremacy and the manifest destiny of the white race.” (104) Such a rant is indistinguishable from what is offered today in a typical history class in most public schools and universities, partially due to the explosion of “black studies” and other courses. While black militant groups failed in most of their political ends, they succeeded in establishing such programs at universities around the country, which not only propagated their ideas but were an invaluable source of funding and patronage.

Eldridge Cleaver (Credit Image: © JT Vintage/Glasshouse via ZUMA Press Wire)

Much of this is simply an extension of what Paulo Freire, a Brazilian academic, taught in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968). “Freire bases his pedagogy on the political belief that capitalism has enslaved the population and ‘anesthetized’ the world’s oppressed with a series of myths: the myth that the oppressive order is a ‘free society’; ‘the myth that all persons are free to work where they wish’; ‘the myth that this order respects human rights’; ‘the myth of private property as fundamental to personal human development’; ‘the myth of the charity and generosity of the elites.’” (145) Such views are hegemonic in schools of education, despite (or perhaps because) of the way “Freire explicitly rationalized violence in Pedagogy of the Oppressed and defended violent revolutionaries such as Lenin, Stalin, Castro, and Mao, who left behind them a trail of up to 90 million dead.” (149)

Mr. Rufo points out that Paulo Freire’s theories didn’t just spread through the public education system but dramatically expanded the potential patronage base of adherents, giving critical theorists both a weapon for ideological enforcement and a jobs program. Citing areas where those theories took root, he writes, “From Guinea-Bissau to the California ghetto, Freire’s theories have never resulted in the meaningful improvement of practical skills, such as reading and writing,” but have merely provided a “relentless critical function,” not a “substantive alternative.” One could argue that that’s not the point. Those theories provide moral justification and material rewards for adherents, thus ensuring their success. Besides, if non-white students can’t perform academically, there’s an excuse for that too — capitalism and racist oppression. Punishment is the point, not success. “The ideal is to punish them in history, not in the imagination,” said Freire. “The ideal is overcoming our weakness and impotence by no longer concerning ourselves with punishing the souls of the unjust, by ‘making them’ wander with cries of remorse. Precisely because it is the live, conscious body of the cruel person that needs to weep, we must punish them in society.” (170)

Paulo Freire (Credit: Slobodan Dimitrov, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The leftist premise that the human consciousness exists to be “engineered” is central to understanding our situation. Race is perhaps the most important part of this because critical theorists link whiteness to oppression. Though race is presumably just a social construct, whites are nonetheless “infected” by various psychological evils. Mr. Rufo quotes Barbara Applebaum, author of Being White, Being Good (2010): “All whites, by virtue of systemic white privilege that is inseparable from white ways of being, are impacted in the production and reproduction of systemic racial injustice.” He cites another pair of critical pedagogists, who wrote, “A big step would be for whites to admit that we are racist, and then consider what to do about it.” (175)

The obvious conclusion is to do whatever the experts tell us, which, conveniently enough, would give them nearly unlimited power. This view is mainstream at the highest levels of the Left. As Justice Jackson in her dissent against the Supreme Court’s recent affirmative action ruling declared, “The only way out of this morass [of racial inequality] — for all of us— is to stare at racial disparity unblinkingly, and then do what evidence and experts tell us is required to level the playing field and march forward together, collectively striving to achieve true equality for all Americans.” Of course, if equal protection and constitutional norms are to be secondary to expert advice about the allegedly desirable goal of “true equality,” law essentially no longer exists in any real sense.

This is precisely what critical race theory advocates when it comes to the law. The key thinker profiled here is Derrick Bell, a lawyer and civil rights activist who became one of the most influential founders of critical race theory. The Constitution, he argued, is not a “hallowed document,” but simply a way to protect whites’ investments, including in land and slaves. (223) Indeed, everything America has done, even acts like the Emancipation Proclamation, were simply cynical moves to protect white interests, and all black successes have ultimately served the interests of white elites. No progress is ever possible, thus feeding Bell’s endless sense of resentment. (229) Mr. Rufo accurately writes that Bell made a “fetish out of white evil and black despair.” One wishes white conservatives would understand that this reception is typical.

Derrick Bell (Credit: I, DavidShankbone, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Though critical race theory began in the universities, we can see that racial resentment is now mainstream, the subtext in movies, television shows, and even commercials. Mr. Rufo argues that the theory is a “near-perfect transposition of race onto the basic structures of Marxist theory.” In that transposition, he writes: “’White supremacy’ replaces ‘capitalism’ as the totalizing system. ‘White and black’ replaces ‘bourgeoisie and proletariat’ as the ‘oppressor and oppressed.’ ‘Abolition’ replaces ‘revolution’ as the method of ‘liberation.'” (234)

Though some may not like the term Cultural Marxism, that is essentially what critical race theory is. It’s actually even worse than Marxism. While Marxism at least aspired to be rational and scientific, the “nebulous epistemological foundation of critical race theory” turns law, objectivity, and even the pursuit of knowledge into nonsense. “[P]ersonal offense becomes objective reality; evidence gives way to ideology; [and] ideology replaces rationality as the basis of intellectual authority.” (236)

Black scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., no conservative, used a kind of critical theory against critical race theorists in legal departments in a 1993 New Republic article:

[The critical race theorists] were members of a privileged class with significant institutional support. They could appeal to the institutions for protection against “hate speech” because they knew the institutions were likely to side with them. The critical race theorists used their identity as the “victim” in order to exploit the moral power of the oppressed minority, while in reality they represented an ideological majority that sought to cement its own power. (246)

This critique is powerful but has done nothing to dislodge critical race theory’s hegemony in law schools and academia generally. Perhaps the best way to look at critical theory is not as a way of understanding the world, but as effective political technology for building power. To their credit, critical theorists never shied away from the reality that their ideas were about building power, not simply philosophizing.

What does Mr. Rufo specifically endorse for a counter-revolution? He gives us a partial roadmap at best. He is practical about the sources of DEI’s power, noting that “critical ideologies are a creature of the state, completely subsidized by the public through direct financing, university loan schemes, bureaucratic capture, and the civil rights regulatory apparatus.” (270) He argues that the “working class is more anti-revolutionary today than at any time during the upheaval. The common citizens have seen the consequences of elite ideology as public policy.” (274) Because these ideologies can’t deliver positive results, he regards them as vulnerable.

That might be self-delusory. Mr. Rufo outlines left-wing abuses in cities like Seattle and Portland, with an extended section on Seattle’s Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) experiment. However, such excesses haven’t displaced leftist power in those cities. While leftists have had to back away from “defund the police” in some areas, cities like San Francisco and Minneapolis remain reliably leftist despite rising crime. Chicago has actually become more liberal in response to surging crime. The language of “safety” and “trauma” has been successfully used to censor the internet.

“The ugly secret is that the radical Left cannot replace what it destroys,” writes Mr. Rufo. (274) However, if destruction is the point, the Left doesn’t have to replace what it destroys. The existing system is an effective way of justifying rule over key institutions, providing patronage to followers and excluding enemies. An organized minority will always triumph over an unorganized majority. The American Right is not uniting behind a cause the same way the Left is united against “hate.”

Mr. Rufo charges that the logical conclusion of “liberation” is nihilism. That may be true, but the utopian goal of demanding equity has proven morally compelling for centuries, justifying the most violent upheavals. Few learn from the excesses, but if you have control over media, you don’t need to. Marcuse and other critical theorists do have much to teach us, but their theories apply more effectively to the system of control he and his disciples built and the way material prosperity “anesthetizes” whites to accept displacement, subjugation, and humiliation.

“The truth is that, despite a half century of denigration, most Americans still believe in the Declaration and the promise of liberty and equality,” Mr. Rufo writes. (279) However, that might be part of the problem. There’s no scenario where “liberty” and “equality,” let alone “equity,” can be reconciled. The Founders really did believe in race and were, in contemporary terms, white nationalists. America really was a nation, a white nation, that triumphed over other nations and established an order that we benefit from today. If we concede the premises that the system must be universalist, “colorblind,” and “anti-racist,” we risk encouraging the same egalitarian impulses that have led us to this point.

Of course, the beginning of conservative wisdom is to realize that one should not try to “immanentize the eschaton” (i.e., bring heaven down to Earth). That’s impossible, and it will lead only to more suffering. Mr. Rufo knows this. However, if we agree with leftists that we want “liberty and equality” too, and that we are just disagreeing about the means, the young, suggestible, and idealistic will rally to the side that promises easy answers and at least the potential for a final victory.

In a far more conservative time, the American mythology of 1776 was unable to prevent the thinkers Mr. Rufo writes about from easily conquering American institutions with hardly any resistance. The same creed is unlikely to inspire the sacrifice and dedication needed to drive those thinkers back. Whites must rally as whites to reclaim their birthright, not appeal to ideas and symbols that few others believe in anyway. The quest for a “colorblind” civic meritocracy has been pursued across the Western world since World War II, and there is little to show for it besides a self-loathing, suicidal civilization in its end state.

This isn’t to denigrate Mr. Rufo or his efforts. His book is valuable reading. He doesn’t retreat to abstractions. He is realistic about power. He is far more sophisticated and effective than any conservative activist since the late Phyllis Schlafly. Nonetheless, we white advocates shouldn’t kid ourselves that he is one of us — not that he pretends to be. He is simply fighting against the forces of resentment, hatred, and entropy that have destroyed our leading institutions and threaten to destroy us as a people. Whatever our disagreements, that effort is something to be supported, and his experiences and scholarship are worthy of attention and admiration.