‘Elvis’ and the Breakdown of American Identity

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, October 14, 2022

Credit Image: © Roadshow Entertainment/Entertainment Pictures/ZUMAPRESS.com

Men sometimes blindly take ideas to their logical conclusion. Thomas Jefferson didn’t literally mean “all men are created equal,” but he set in motion forces now destroying his nation. Northern soldiers in the Civil War may have thought they were fighting to save the Union, but their victory redefined it. American soldiers in World War II thought they were fighting for their country, but the anti-racist and anti-fascist “Crusade in Europe” eventually turned against America itself.

Those who change the world usually do so on purpose. Success or failure should be judged based on whether someone achieves his goals, not what other people see as his accomplishments. Many say Winston Churchill is a hero because he led Britain to victory in the Second World War. I say he’s a failure because he did more than anyone else to destroy the British Empire he so loved.

From that perspective, what can we say about Elvis Presley, arguably the most influential American musician? He was and is “The King,” with a following so passionate that many still refuse to believe he is dead. He changed music by mixing “black” gospel and R&B with “white” country and rockabilly, giving us true rock and roll.

Australian director Baz Luhrmann’s biopic Elvis will make him a hero to a younger audience. It does this by ignoring Presley’s later doubts about the world he helped create. From the perspective of 2022, Elvis’s most reactionary critics were right about what he unleashed.

Elvis represents a moment in American history when a post-racial, patriotic, color-blind identity seemed possible. It’s an appealing vision. It’s one reason The King still wears his cultural crown. Yet it was never realistic, and Elvis glorifies its hero by avoiding the hard questions.

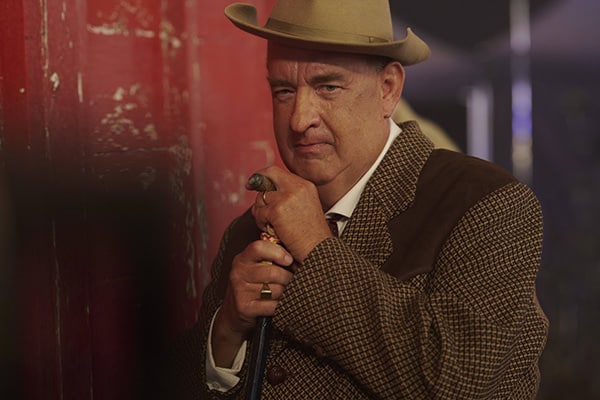

This doesn’t mean it’s a bad film. Baz Luhrmann’s flashy style is ideally suited to this subject, though it would be ridiculous with anyone else. Mr. Luhrmann throws us straight into the gaudy glory of Elvis’s live performances in the 1970s. A corpulent King still triumphantly belts out classics to an adoring audience. Rather than treating the later Elvis as a joke, Luhrmann reminds us that even at his worst, he was still the most famous artist in the world. We also get our foil, the villainous Colonel Tom Parker — Elvis’s manager — played by Tom Hanks.

Star Austin Butler does the impossible, convincingly playing Elvis without being an “Elvis impersonator.” Presley himself never won an Oscar during his long movie career, but Mr. Butler deserves one, capturing Elvis’s spirit, style, and voice, while changing it just enough so it isn’t bland mimicry.

Butler’s Elvis is more effeminate, wears more makeup, and is less country than the real thing. In the trailer, a heckler taunts Elvis by calling him “buttercup;” in the film, someone calls him a “fairy.” This may be deliberate; in woke America, an accusation of bisexuality gives a star more appeal. Moreover, Elvis’s performance quickly wins over all the girlfriends of characters who say insulting things about homosexuals. Mr. Luhrmann repeatedly zooms in on the Elvis’s crotch if you don’t get the message.

This doesn’t mean Butler’s Elvis comes off like a sissy. He dominates every scene he’s in, and masters the smallest gestures without overdoing them. Mr. Butler did his homework; he captures the visibly nervous Elvis shakily reaching for the microphone during the 1968 “Comeback Special” and his self-conscious laughter during “Jailhouse Rock.” The movie version of The King will appeal to those who remember him live and those discovering him for the first time. Playing Elvis Presley is probably the most difficult role in film because there are so many impersonators. Mr. Butler succeeds.

In contrast, Tom Hanks’s “Colonel Tom Parker” — real name Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk — is a comic grotesque. The Colonel (his title was an honor he got from a politician he helped) was a carnival-working illegal immigrant from Holland, and a conman. Horrible prosthetics, a nonsensical accent that comes and goes, and a buffoonish waddle make the allegedly evil genius hard to take seriously. Mr. Hanks’s performance is so bad it almost kills the film. The devil must be attractive to ensnare the innocent; this Parker looks like he came from the set of Adam West’s Batman. This matters, because the film blames “The Colonel” and his supposed powers of seduction for everything bad that happens.

Tom Hanks as Colonel Tom Parker. (Credit Image: © Roadshow Entertainment/Entertainment Pictures/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Perhaps the cartoonish portrayal is the point. Colonel Tom Parker isn’t just the real-life villain but a stand-in for capitalism, conservatism, and timid white convention. The story is told from Parker’s perspective, but Luhrmann clearly takes Elvis’s side. He shows us Elvis, a beautiful soul taken in by Parker, “the Snowman” — a con-artist whose cheated both Elvis and his audience.

A one-sentence review would be that Elvis is a story about an illegal immigrant who ruins an American musician’s life.

Despite Mr. Butler’s magnetism, his Elvis is mostly passive. With few exceptions, things happen only to him. The film’s Elvis has talent but rarely makes or does anything. Instead, he absorbs and imitates black music. Perhaps in a nod to today’s endless Marvel movies, Mr. Luhrmann gives us a “superhero” whose special power is that he can absorb black musical talent.

The young, impoverished Elvis lives in a black neighborhood but dreams of bigger things. He wears his hero Captain Marvel Jr.’s lightning bolt. (Mercifully, the script avoids Captain Marvel Jr.’s origin story involving “Captain Nazi.”) Surrounded by black playmates, the young Elvis voyeuristically spies on an almost pornographic blues performance and then runs into a religious revival, where a black preacher says he has “the spirit.” Mr. Luhrmann ignores the conflict between the sacred and the profane that the Ray Charles biopic Ray acknowledged. Instead, the two styles blend into black music that excites whites. In the movie, Elvis gets his big break only because he’s white.

Mr. Luhrmann’s dedication to this theme results in some huge distortions and slurs. Presley tours with country star Hank Snow, who is portrayed as a boring, bigoted prude who despises Presley. This isn’t true. Snow was a star in his own right and helped the young Elvis before Colonel Parker won full control over the naïve star. Snow’s three-decade career was very successful, and he’s the reason most know the song “I’ve Been Everywhere,” later recorded by Johnny Cash and sampled by Rihanna. In the movie, he and his pathetic son are just punchlines, as are country music fans and Southerners. This is especially stupid because Snow was Canadian and his son became a minister, not some failed Elvis wannabe.

Many saw the young Elvis’s moves and style as vulgar and threatening. The film implies that powerful, unnamed men force Colonel Parker to change Presley into the staid “New Elvis,” fit for family consumption. Parker, who knows nothing about music but wants to cash in with cheap merchandise and mass appeal, is willing to sacrifice Elvis’s appeal. To him, it’s all just a carnival act to separate rubes from money. In this film, white Southerners apparently control the media, because they make their demands to Parker in an ominous boardroom featuring a picture of Stonewall Jackson. This culminates in Elvis’s humiliating performance on the Steve Allen show, dressed in tails and singing to an actual hound dog.

In yet another “numinous Negro” trope, Elvis must flee all the whites tearing him apart, including his own family, and rediscover his true self among the spirited blacks on Beale Street in Memphis. Well-dressed, respectful blacks greet Elvis with dignity instead of screaming like lunatics the way white fans do. Mr. Luhrmann puts a hip-hop soundtrack into 1950s Memphis to make it seem modern, but Beale Street today is a tourist trap in what may be the most dangerous city in America.

A. Schwab is the oldest business on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee. (Credit Image: © Karen Focht/ZUMA Press Wire)

“Now listen up, while brown America speaks!” declares a black radio host as we behold Beale Street looking far better than it does today. Mr. Luhrmann tries to defend Elvis from charges of “cultural appropriation” by showing him doing just that. Elvis sits, listens, and implicitly acknowledges blacks’ superiority, adoringly watching them play and sing. The film shows us Little Richard, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and the hard-drinking “Big Mama” Thornton of “Hound Dog” fame. When Elvis plays his first single “That’s All Right,” the film repeatedly flashes back to black bluesman Arthur Crudup playing it. Mr. Luhrmann is careful to show that this music came entirely from blacks; we never see what Elvis learned from country music or any other sources. It’s implied that he learned nothing.

The film also suggests the young Elvis and B.B. King were close friends, with the pair shopping for clothes together and King offering wise counsel to the confused performer. King tells Elvis he can make more money than “that kid” (Little Richard) ever could. The trailer implies King is telling Elvis he has more opportunities because he’s white, but King is also warning Elvis. He tells him he needs to have total control over his career and that he needn’t fear jail, but that’s because “too many people are making money off you.” B.B. King spoke highly of Elvis, though it’s doubtful they were close in real life.

Austin Butler as Elvis and Kelvin Harrison Jr. as B.B. KIng. (Credit Image: © Roadshow Entertainment/Entertainment Pictures/ZUMAPRESS.com)

The film suggests that during Elvis’s early career, segregationist senator Jim Eastland was his main political opposition. Eastland was last in the news when President Biden fondly remembered him as a mentor and friend. Always portrayed with dull colors unless alongside blood-red Confederate flags, Eastland rages about a “white boy from Memphis moving like a goddamn [assumed slur].” Interestingly, both Presley and Eastland imply that the media are trying to force a cultural change. Elvis swears “those New York people ain’t gonna change me none,” while Eastland charges those who “control and dominate the entertainment industry” are “determined to spread Africanized culture.”

There is a showdown when Elvis defies warnings not even to wiggle a finger and instead delivers a sexually charged performance of “Trouble” that breaks down segregation entirely among the audience. Apparently, young people were just waiting for Elvis to gyrate to put an end the Old South. The police eventually stop the show, and the movie implies that powerful people directly threatened Elvis with jail or the army.

Of course, Mr. Luhrmann is just making things up. Elvis was drafted. Colonel Parker and Elvis talked about how it could help his career; it was not a dark plot from on high to stop a cultural revolution. The Army even gave him a special delay so he could finish King Creole, which some consider his best movie. It may have been for careerist reasons, but Presley refused special treatment in the military and served honorably, eventually becoming a sergeant. The film suggests that Elvis’s military service so upset his mother that it led to her death. It may have contributed, but Elvis’s touring and popularity would have led to the same drinking habit and early death. Mr. Luhrmann turns Elvis into something close to a conscientious objector when there’s no evidence for this.

The director also avoids awkward questions about Elvis’s courtship of Priscilla Presley, who was just 14 when he met her. Today, we’d call it grooming, though it was more acceptable then. Elvis’s affairs with various other women are not shown. Though the marriage is a threat to Parker in the film, Elvis’s manager had actually encouraged marriage to help the star’s image.

The movie essentially skips Elvis’s film career. There’s a shot of the movie poster for Flaming Star, and Parker claims Elvis was “as good as Brando.” Flaming Star was probably his best movie and the most interesting from a racial perspective. Elvis plays a “half-breed,” who spends the movie fighting both racist whites (including a group that tries to rape his Indian mother) and Indians who attack his white father and brother. His character, “Pacer,” a mixed race victim of discrimination, is bitter because whites see him as barely better than a savage. The message was so radical some countries restricted the film. Since Mr. Luhrmann presents the young Elvis as something close to a civil rights activist, it’s incredible he doesn’t highlight this film. However, if critics are reminded that Elvis played an Indian, there could be reviews accusing Elvis of being another Rachel Dolezal. Colonel Parker blames audiences for not wanting to see Elvis in dramatic roles, and Elvis stars mostly in light musicals,

The film basically skips a decade, and suddenly, out of nowhere, Elvis realizes that the culture has changed. Once again, blacks are the key to enlightenment. Elvis watches blacks singing and suffering after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. While watching gospel singer Mahalia Jackson sing at King’s funeral, Elvis says “that’s the kind of music that makes me happy.” It’s an odd thing to say about a sad song at a funeral, but Mr. Luhrmann seems determined to show Presley merely as a vessel of superior black musical traditions, almost someone who wanted to be black. Thus, in a movie called Elvis, we learn little about Elvis and more about the blacks who influenced him.

Mr. Luhrmann wildly exaggerates a conflict between Colonel Parker and Elvis over the 1968 “Comeback Special” that relaunched his musical career. Parker initially wanted a Christmas special, but Mr. Luhrmann makes it seem like Elvis sprang an entirely new program on his manager and sponsors without telling anyone. Colonel Parker complains about hippies and radicals, while Elvis sings spirituals and talks about how rock and roll grew out of gospel and rhythm and blues. Colonel Parker just wants to make money, but the film implies Elvis is not just reconnecting with his roots in his Comeback Special, but making a statement about racial justice.

Mr. Luhrmann makes it seem that the final song in the comeback, “If I Can Dream,” a tribute to assassinated leaders Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, was a surprise move by Elvis to thwart his conservative manager. The film even suggests there was a giant Christmas background and backup dancers that Elvis ignored to sing his protest song instead. No production would ever work that way, and the Colonel obviously knew months in advance what songs Elvis would sing. The film is giving us a fake conflict to make Elvis seem more courageous and rebellious.

The film treats this song like a profound statement by Elvis against racial injustice. It certainly shows Elvis was a great singer, but the lyrics are not revolutionary. Anyone can agree with the message of people working together and living in harmony. Besides, it’s Elvis’s name in giant letters at the finale, not that of King or Kennedy. Elvis raises his arms in triumph; he doesn’t take a knee.

After this glorious comeback, Mr. Luhrmann takes us back to Las Vegas and a live show at the International Hotel. Finally, Mr. Luhrmann lets us see what Elvis can do when he’s not just channeling other performers. Elvis didn’t just entertain an audience, he also conducted an orchestra and two teams of backup dancers just by moving his body. No one else has done it since. Elvis’s early performances in Las Vegas were his peak, not an embarrassing decline. Still, Mr. Luhrmann again reminds us that Presley’s triumph is built on bluesman Arthur Crudup’s original version of “That’s All Right.”

After Elvis’s triumph in Las Vegas, Mr. Luhrmann somehow loses the plot. The director seems confused about how to end the film. I kept expecting B.B. King to show up to offer wisdom, but Elvis’s friend seems to be gone for no reason. The Colonel practically enslaves Elvis with a contract that commits him to an impossible work schedule. He does this so he can pay off gambling debts. Everything bad that happens to Elvis is Parker’s fault.

- Why can’t Elvis go on an international tour?

- Why must he keep working a schedule that is clearly killing him?

- Why does Elvis become addicted to drugs, ultimately causing Priscilla to leave him?

- Why doesn’t Elvis go back to playing shows with people like B.B. King?

- Why doesn’t Elvis get a career-defining role in A Star Is Born opposite Barbara Streisand?

The answer to all these questions is, “The Colonel.”

The film makes us hate a character who was already despicable from the beginning. That’s not much of an accomplishment.

Elvis finally fires The Colonel on stage, which would be thrilling, except it never happened. He goes back to slaving away in Las Vegas, singing with everything he has, even though he’s physically falling apart. He dies at 42, looking like he’s 62.

This would be a suitable ending to a tragedy about Elvis, the man, but the film is going in too many directions at once. The first half presents Elvis as a racial crusader and a threat to the system. After that, it veers into standard musical biopic territory about the dangers of fame and fortune before pinning everything bad on Parker. It’s like Mr. Luhrmann intended to make a political film, but ran out of material halfway through.

Elvis was not a racist, but he wasn’t a radical. Black musicians don’t play much of a role in Elvis after the beginning. The sentimental, vague lyrics of “If I Can Dream” are moving, but hardly challenging, so Mr. Luhrmann just ends the film, with the all the political buildup leading nowhere.

The true explanation may be that Mr. Luhrmann is protecting his subject. Throughout the film, one can sense Mr. Luhrmann’s paranoia about racism. The conservative South is portrayed as backward and bigoted. However, Elvis never disavowed his Southern roots. His “American Trilogy,” featured at the very beginning of the film, may end with “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” but it begins with “Dixie.” Given that the Confederate flag has an almost demonic aura in this movie, Mr. Luhrmann can hardly suggest anything positive about the Confederacy.

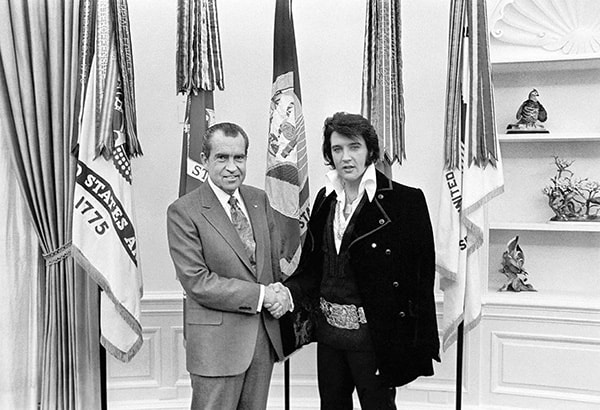

He also can’t cite anything Elvis said about politics in the latter part of his life. Elvis was politically conservative by the late 1960s, which makes it hard for Mr. Luhrmann to keep presenting him as a threat to the system. Pat Buchanan remembered this in Nixon’s White House Wars:

On December 21, 1970, Elvis Presley showed up at the White House gate and asked to meet with President Nixon. As West Wing receptionist, Shelley [Buchanan] greeted the legend who had come to have Nixon designate him a ‘Federal Agent at Large’ in the war on drugs. Elvis surrendered his guns to the Secret Service and, escorted into the Oval Office by Bud Krough, told Nixon that he could get through to the kids and, incidentally, that the Beatles were anti-American. A surprised Nixon added that those who use drugs were in the vanguard of anti-Americanism. ‘I am on your side,’ Elvis told Nixon, saying that respect for the flag was being lost, and, as a ‘poor boy’ from Tennessee who had done well, he wanted to repay America. Before departing, Elvis threw an arm around the President and gave him a hug. [p. 198]

Mr. Luhrmann probably did not want to show Elvis, still in shape and at the height of his career, telling Richard Nixon what the singer had learned from studying “Communist brainwashing techniques.”

Elvis Presley meeting with President Richard Nixon at the White House on December 21, 1970 (Credit Image: © Circa Images/Glasshouse via ZUMA Press Wire)

Mr. Luhrmann is trying to claim Elvis for progressives — and ultimately he’s right to do so. Elvis was a battering ram that let through the cultural changes of the sixties, especially views on race and sex. Elvis probably did not foresee all this, and had he lived, would not have liked where it led. Nonetheless, it remains his legacy. “The Sixties were great, but only musically,” said Rep. Sonny Bono, and even that is dubious.

Elvis’s impact can be seen in modern pop culture. Mr. Luhrmann celebrates the King’s legacy in the soundtrack by mixing his songs with modern music, thus proving that Senator Eastland was on to something when he warned about the Africanization of American culture.

Still, Elvis has his place among whites. “The day Elvis passed away would be our national holiday,” sang Hank Williams Jr. in “If the South Woulda Won.” He captured a certain defiant, outlaw spirit. Elvis was and remains quintessentially American.

The King also relates to both whites and blacks. It’s impossible to segregate “black” or “white” music when it comes to country and rock. B.B. King himself credits Jimmy Rogers, a white country singer known for his yodeling, as one of his own influences. Defending Elvis from charges of cultural appropriation, King argued that there was a constant exchange between white and black musicians. There was so much interplay that it would be impossible to say where black music stops and white music begins. For example, “Big Mama” Thornton is exhibit A for those who say Elvis stole black music, in this case “Hound Dog.” However, she didn’t write “Hound Dog.” Two Jewish men named Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller did. Did “Big Mama” culturally expropriate the Jews?

Yet that was then, and the situation now is more divisive in some ways than during segregation. Few, perhaps no one other than white conservatives, believe in the “colorblind” promise of a common American identity. For his time, Elvis was progressive because he worked with and among blacks in the South. Today, our rulers say colorblindness itself is racism. Furthermore, white cultural symbols and traditions, especially those connected to the South, are inherently evil and must be scorned. That would mean ditching not just Elvis, but Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, Dwight Yoakam, Hank Williams I, II, and III, and countless others.

Besides, the very concept of “cultural appropriation” means that cultural exchange can’t take place. Whites, especially, must be careful not to “co-opt” another race’s culture, and it’s equally scandalous to claim a genre or subculture is white. Whites are not permitted any identity other than a negative one.

Elvis Presley is like this in Elvis, almost a ghost in his own biopic. He dominates every scene, his voice and power attract our attention, but it’s hard to say who he actually is or what he thinks. Mr. Luhrmann’s frantic editing and quick shots can’t cover up the gaping holes. What white musicians influenced Elvis? What did he think about America near the end of his life? What responsibility did he bear for the terrible things that happened to him and his family, including his drug addiction, adulteries, and wild spending?

Mr. Luhrmann either makes things up or avoids these questions to protect his subject. He gives us a politically correct Elvis the same way we have a politically correct Martin Luther King Jr. It’s useful as a unifying figure for America, but it falls apart if you look closely. It makes Elvis bland. It may make him safe for easily offended modern audiences, but the real story is more interesting.

Elvis is important because no contemporary musicians are familiar to a mass audience the way Elvis was. His 1968 Comeback Special attracted 42 percent of the total national television audience at the time. If you were American, you knew Elvis.

Now, America is importing peoples from all over the world with their own tribal symbols, languages, hatreds, and taboos. “Americans” have few things in common. Even pop culture is divided into niches. Our rulers rip open the wounds of the past, such as the “Tulsa Massacre” or Emmett Till, often exaggerating what actually happened. There’s no longer the pretense of unifying America even under a noble lie like colorblindness. For that reason, a musician cannot be apolitical. Artists parrot progressive views lest they be canceled. It may have been best for his legacy that Elvis died young. Critics would have destroyed him if he had lived longer.

Mr. Luhrmann’s film is a noble lie. The King brought joy to crowds around the country because of the way he threw himself into his performances. That’s not enough today, so Mr. Luhrmann carefully guards him, very deliberately citing his black cultural influences, ignoring his white ones, erasing his political views, and giving him a victim status he didn’t have. Elvis — the gun-toting former soldier worried about the decline in patriotism — thus becomes the misunderstood victim exploited by a capitalist manager and a system that wanted to profit from black music without helping black people. Elvis was the talented, well-meaning, naïve front man for an evil system.

Modern America doesn’t want a King, it wants a victim. Mr. Luhrmann gives us that but at least lets him sing. It’s entertaining, but Mr. Luhrmann may have hollowed out Elvis more than Colonel Parker ever did. Besides, when you walk out of the theater and look around, Joe Biden’s old friend Senator Eastland doesn’t seem so stodgy and paranoid after all.

After the thrill of transgression is gone, decadence becomes just another product. Today, vulgarity is standard and therefore boring, and today’s entertainers lack the talent and vitality Elvis had even at his worst. The reason is that Elvis drew on traditions of the rural South, white and black, that were real, raw, and had something to say. Today, everything is suffused in irony, self-awareness, and political cowardice. The result is that the traditional, staid, conservative culture that Elvis unwittingly destroyed is far more interesting than what we have today.