The 1865 Project

Anthony Bryan, American Renaissance, June 10, 2022

The movement resembled a Crusade, but a crusade which stands alone in history. It was not a union of different countries and different races under a religious inspiration against a common foe; it was conducted by men of one race against others of the same race, within a common country, and yet for the benefit of a different race. — Peter Joseph Hamilton, History of North America, Vol. 16; The Reconstruction Period, p. 12.

In 2019, the New York Times Magazine published a series of articles with the theme that the true date of America’s birth was 1619. The anchor piece of this 1619 Project series, called “The Idea of America,” asserts that the arrival of African slaves to the Virginia Bay Colony was the start of everything that was, and is, essential to the United States. The author further claims that blacks deserve credit for nearly all of America’s accomplishments and positive attributes. “The United States would simply not exist without us,” she declared. A number of articles by other black writers follow in the same vein, finding links between slavery and all sorts of modern practices including the use of Excel spreadsheets.

The 1619 Project is a more detailed version of the “we built this country” claim, and it is rooted in the same solipsism and indignation that motivates most black political and cultural commentary. Giving blacks credit for America’s achievements is like giving a hospital’s janitors credit for a successful heart transplant. In a sane age, the 1619 Project would be something handed out as a pamphlet on street corners. But we don’t live in a sane age, thanks to white liberals. It is their policy of credulity and indulgence regarding black grievances that gave the 1619 Project prominence in elite circles and mainstream media, and makes it an addition to school curricula.

Some academic historians, including some on the Left, gamely took up the cause of challenging the 1619 Project’s assertions and did the fact checking that the editors at the New York Times Magazine didn’t. But the 1619ers mostly shrugged off factual errors. Their mission was to push an agenda of white guilt, and they were not going to be deterred by details. Although the fact checkers were in the right historically, they missed the forest for the trees in assuming that the 1619 Project was about historical scholarship instead of racial revanchism.

A number of other efforts were undertaken to counter the claims that slavery is the essence of America. The 1620 Project, for example, argued that it was the Mayflower Compact that set the stage for the American form of government, but most of the others dated America from the year 1776 and the Declaration of Independence. President Donald Trump set up a 1776 Advisory Commission; a 1776 Project Political Action Committee raised more than $2 million; black conservatives created the 1776 Unites project; and Hillsdale College offered a 1776 curriculum. The premise was generally that the principles of liberty and self-government are what really define America.

There are three consistent rhetorical patterns to the 1776 approach. The first is to denounce slavery and racism. The second is to cite the words “all men are created equal” from the Declaration of Independence. Although Thomas Jefferson would surely delete that line if he could see what it has wrought, and although it is demonstrably untrue, it is repeated over and over as evidence that America is of good will and noble heart. The third is to quote Martin Luther King, Jr.: “We should judge people by the content of their character.” Mainstream conservatives, especially white ones, love this sentence, and often invoke MLK’s “dream” to claim that liberals are the “real racists” because of their woke refrains and support of affirmative action, quotas, etc.

The Republican appeal to color-blind civic nationalism is no match for the vengeful emotionalism of the 1619 Project. But this asymmetry is typical of racial discussions in America — blacks, with the backing of liberal whites, aggressively push whatever argument or policy benefits them, while the “MLK-Cons” respond with feeble appeals to the Constitution and universal principles.

The 1619ers have a point that the importation of Africans into North America and the resulting population of millions of blacks is a defining aspect of American history. And in many ways, 1619 is indeed more formative than 1776. When Americans ride public transit, attend public schools, and go to the state fair, they feel the legacy of slavery more deeply than the legacy of the Constitutional Convention.

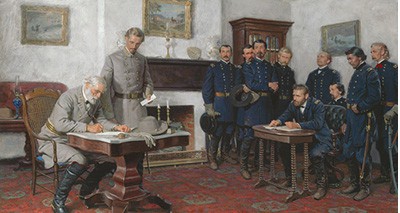

But more than the mere presence of blacks, what affects white Americans in 2022 is their collective relationship with blacks. And today’s black-white relations started, in a legal sense, after the Civil War. In 1865, after the bloody conflict ended, a “political cold war” began, in which whites tried to determine what to do with the newly freed black population. The 13th Amendment, formally outlawing slavery, was ratified at the end of 1865. Over the next five years, Congressional Republicans proceeded to further amend the Constitution to give blacks citizenship and the right to vote, effectively creating a new arrangement of American life. Ever since, white elites in Washington D.C. have claimed for themselves the legal and moral authority to dictate the relations between the states and their citizens in the name of protecting blacks and their post-1865 rights.

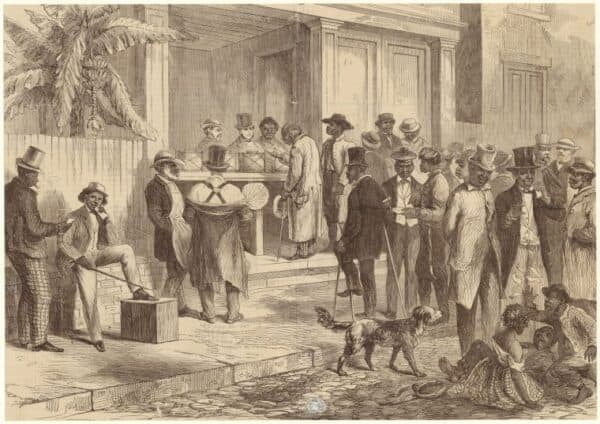

Freedmen voting in New Orleans, 1867.

During Reconstruction, the Radical Republicans used their dominant post-war position to force their desired political and social arrangements on Southerners, prevented them from governing themselves, turned away their elected Congressional representatives, and used the army to ensure they obeyed. It was a period of rule more in the tradition of European monarchs than classical republicanism. It also marked the end of “1776 America,” and the beginning of what could be called “the 1865 Project.”

Jefferson once said slavery in America was like holding a wolf by the ears. Many early Americans opposed outright abolition precisely for fear of the wolf unleashed. But after the Civil War, the zeal for “equality” and the zeal for punishing the South overtook practical considerations about racial harmony and social cohesion. The political elites of the 1860s and 1870s did almost nothing to mitigate the possibility of conflict between whites and blacks. Or as W.E.B. DuBois himself said, “Thus Negro suffrage ended a civil war by beginning a race feud.”

The 1865 Project created predictable backlash and animosity over the subsequent decades in the South, and many blacks eventually headed north. Even then, “equality” remained elusive. So by the 1950s and 1960s, a very white and very prosperous American elite decided once again to reconstruct America in the pursuit of racial equality. This time, it would dictate not just the relationship between government and citizen but between businesses and customers and between individual whites and blacks.

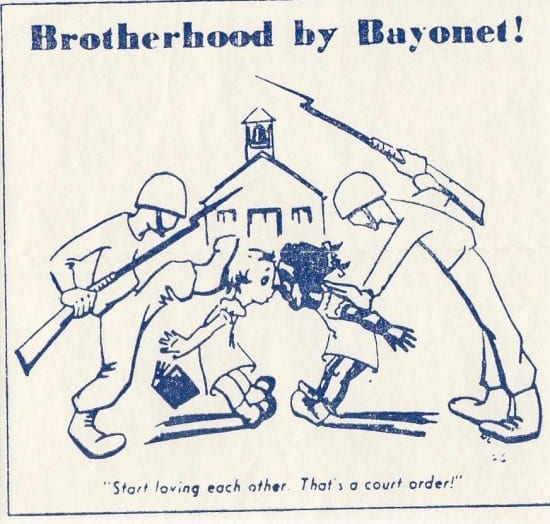

Through more legislation and a series of Supreme Court rulings, these new radicals, now operating through the Democrat Party, supercharged the 1865 Project. Voter registration, hiring decisions, education, and housing all came under the purview of the federal government in order to protect blacks from discrimination. And, as in the 1860s, men with guns were brought in when white citizens showed too much defiance in resisting these changes. Just as with the first, the second wave of the 1865 Project did not bring about racial harmony or equality. In fact, in the years following the “Civil Rights movement,” race relations became worse, with riots and increases in violent crime.

The 1865 Project is the product of a certain kind of white mind. Whether called Radicals or bleeding-heart liberals or social justice warriors, the mentality is the same. These people see themselves as the hero in a fairy tale of good versus evil. They relish the opportunity to intervene on behalf of supposedly downtrodden black people. They never view the concerns of white dissenters as legitimate or worthy of consideration, and this justifies any manner of restrictions or punishment. Some even seem to get a thrill from humiliating less enlightened whites. Their intraracial spitefulness fuels an appetite for “poetic justice,” whether it be converting Jefferson Davis’ plantation into a Freedmen’s Farm after the war or melting down a statue of Robert E. Lee in 2021 and giving the metal to a black museum for it to build an “anti-racist” sculpture.

The 1865 Project is a set of legal constraints put on white people by other white people in order to bind them into an unhappy civic marriage with black people. When the multiracial utopia doesn’t arrive, the 1619ers blame the persistence of racism while the 1776ers and MLK-Cons say it’s due to “big government.” What almost no one will say is that the project is fundamentally flawed. It hasn’t worked and it’s not going to work. And the inability to acknowledge this makes everything worse.

In recent decades, the 1865 Project has gotten even worse. It has been expanded from legislative action to a cultural madness that insists on dictating personal behavior and speech in every facet of American life. From celebrating the first black person to do just about anything, to fat black women working as underwear models, to white people literally kneeling in the streets, this third phase of the 1865 Project has produced a constant carnival of absurdities and punishments. And as the proportion of whites in America keeps declining, the implications of this way of life grow more potent and more dire. The New York Times Magazine’s editor had the nerve to add this note to the 1619 Project: “Perhaps we can prepare ourselves for a more just future.” But it is whites who need to prepare themselves for a future that will not be just to them or to their children — and act accordingly.