Remembering Constantinople

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, May 28, 2021

Lars Brownworth, Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization, Random House, 2009, 315 pp., $69.99 (Hardcover), $24.46 (Audiobook), $11.99 (Kindle)

Jean Raspail wrote the most prophetic book of this century, The Camp of the Saints. It ends with the last remnant of the West about to be overrun. The book’s final words are: “The fall of Constantinople is a personal misfortune that happened to all of us only last week.” Tomorrow, May 29, that colossal misfortune will have taken place exactly 568 years ago, in 1453.

“The West” began with the Greek resistance to Persia and the creation of an intellectual, cultural, and racial tradition. Westerners have always fought each other, but “the West” was once united by the ideal (if not the reality) of Empire and the sense of being part of one civilization.

England, France, Germany, and other proud nations are tribes of a greater people. I would argue that their civilization has been shattered for a millennium now. To some extent, our entire racial history is an attempt to return to Rome and the unity it represented. The last manifestation of that unity was the Eastern Roman Empire. In 1399, when one of the final emperors, Manuel II, was touring Europe begging for help, Europeans remembered that the emperor “sat on the throne of the Caesars, and, no matter how debased that throne had become, its dignity was still unparalleled.” [p. 279]

What we now consider the “East,” including Egypt, Anatolia, and the Levant, was once part of our civilization too. For a millennium after Roman power collapsed in Europe, the Roman ideal continued in Constantinople. We often forget that they were us.

Lars Brownworth, a former academic who has become a full-time historian, writes that on the night of May 28, 1453 — the eve of defeat — Emperor Constantine XI Dragases told his men that they were “worthy heirs of the great heroes of Ancient Greece and Rome.” Also, for the first and last time in Byzantine history, Latin and Greek priests stood together and prayed for the city. Mr. Brownworth, quoting Gibbon, calls it the “funeral oration” for the Roman Empire. Italians and Greeks, Catholics and Orthodox, fought shoulder to shoulder on that last terrible day.

19th-century depiction of Emperor Constantine XI Dragases with classical Greco-Roman armor.

In Essential Writings on Race, Sam Francis says that, “The concept of the ‘Last Stand,’ in which an outnumbered army . . . face battle against overwhelming odds, usually without any realistic expectation of victory, recurs throughout Indo-European history and legend — at the battles of Marathon and Thermopylae.” It’s hard to think of a more inspiring example than Emperor Constantine charging into the enemy ranks, knowing that after a 53-day siege, all was lost. His body was never found. Like King Arthur, it is said he will come again.

Who needs fantasy when we have history like this? In Psalm 137, the Jewish author curses himself if he should “forget thee, O Jerusalem.” Should we not feel the same way about Constantinople?

History not only inspires us; it cautions us. Few of us reflect on Constantinople. Both white advocates and our opponents too often assume that whites always win. We are always conquerors, never conquered. This justifies stark racial double standards. Christian Lander, author of Stuff White People Like, unwittingly put it best. “It is always OK to make fun of white people because no unhappy ending is possible.”

Lost to the West reminds us this isn’t so. The fall of Constantinople was horrifying. “Women and children were raped, men were impaled, houses were sacked, and churches were looted and burned,” writes Mr. Brownworth. For Eastern Europe, the end of the Roman Empire meant centuries of political slavery under Ottoman oppression. For more than a million whites, losing the Mediterranean meant literal slavery.

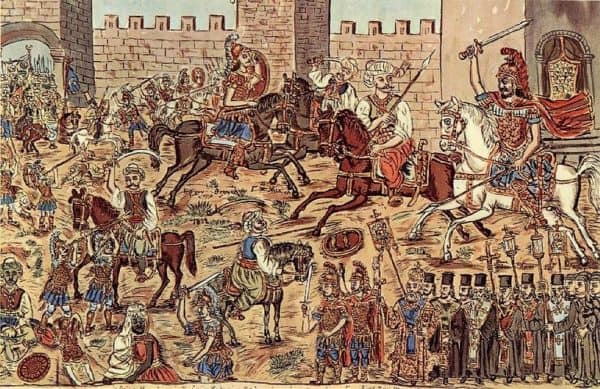

Fall of Constantinople by Theophilos Hatzimihail. Constantine is visible on a white horse.

There’s something worse than slavery. It’s losing an identity. Occupation means living under alien law, morality, and cultural codes. Even before Constantinople fell, the Ottomans had already occupied Eastern Europe. One of the main reasons Constantinople fell was that the elite forces of the Turkish army were “Christians who had been taken from their families while children and forcibly converted to Islam” and who had become “fanatically loyal” to their new masters. [p. 297] A people can rise from defeat, but not from deconstruction.

Constantinople tells us defeat is possible. It has happened before and the consequences were sickening. We still live with them. The Hagia Sophia, the greatest church of antiquity, is a now mosque. A Turkish ruler with neo-Ottoman pretensions uses Muslim migrants slowly to conquer Europe. The political police in Germany said in 2017 that the largest “right-wing extremist” group in the country was the ultranationalist, arguably terrorist Turkish Grey Wolves. Like the empire in its final years, we are increasingly surrounded in what was once unquestionably “our” land.

July 16, 2016 – At least 500 people gathered in front of the Turkish consulate in Munich after attempted military coup in Turkey. Grey Wolves signs were thrown. (Credit Image: © Michael Trammer / ZUMA Wire)

What caused the collapse? The answer is both too broad and too simple: We did. Of course, there was the rise of Islam, disputes between Catholics and Orthodox, and the wisdom or folly of various political and military decisions. Ultimately however, the Ottomans didn’t conquer Constantinople. Europeans destroyed it first.

When Roman authority collapsed in the West, it survived in the East. Technically, the Roman Empire hadn’t ended. In the sixth century, under Justinian and his great general Belisarius, the empire built the Hagia Sophia and reconquered much of the West. However, plague and petty personal disputes limited their accomplishments.

Islam was a powerful new enemy. Yet the decisive blow came when Western European crusaders sacked Constantinople in 1204. After that, it may have been a matter of time before the city fell to the Turks. Nevertheless, three things contributed to the fall, and all apply to our own age.

First, there were white traitors, who put greed ahead of loyalty. Chief among them in 1453 was a Hungarian named Urban, a gunnery expert who served the Byzantines. However, when the nearly exhausted empire couldn’t pay him enough, he went to work for the attacking enemy, Sultan Mehmed II. It was thanks to Urban and his artillery that the Turks breached the walls. White people really are our own worst enemies and Urban’s infamy should equal that of Ephialtes.

Mehmed the Conqueror enters Constantinople, painting by Fausto Zonaro.

The warriors of the Fourth Crusade who sacked the city were also cultural/racial traitors. This wasn’t a battle between Catholicism and Orthodoxy. Pope Innocent III flatly excommunicated the Catholic crusaders because he knew they had destroyed Christian unity. [p. 261] The Venetian doge Enrico Dandolo manipulated the crusader army into sacking the city for profit, and ensured supremacy for his city. However:

[I]n doing so he had perpetuated one of the great tragedies of human history. Byzantium, the mighty Christian bulwark that had sheltered western Europe from the rising tide of Islam for so many centuries, had been shattered beyond repair—wrecked by men who claimed that they were serving God. Blinded by their avarice and manipulated by the doge, the crusading leaders broke the great Christian power of the East, condemning the crippled remnants—and much of eastern Europe—to five centuries of a living death under the heel of the Turks. [p. 258]

You could say the doge served Venice by destroying Constantinople, but by destroying the empire, he ruined Venice because under Turkish rule it was no longer a gateway to the east. Leaders can’t afford to be individualistic, or even always loyal to their polity. They have to take a racial and civilizational view if they want to serve their people. A victory over a rival polity is self-defeating if it weakens your race and civilization.

The second factor that destroyed the empire was the short-sightedness of selfish elites. If our schools taught heroism instead of shame, our children would know about General Belisarius. However, he could have done far more were it not for the jealousy of the emperor’s wife Theodora, who saw him as a threat. Another general of the time, Narses, was unnecessarily insulted, and then invited the Lombards to invade Italy. [p. 118] The Great Schism itself, which permanently divided the Catholic and Orthodox churches, wasn’t really about theology. It was about two petty men, one a Catholic cardinal and the other the Eastern patriarch, socially snubbing each other. [pp. 223–224] Byzantine history has countless plots, poisonings, and coups that killed successful generals or emperors.

Hagia Sophia, the cathedral of Constantinople at the time of the schism. (Credit Image: Slimm via Wikimedia)

Personal failings are discouraging, but are common in history. Just as we see today, selfish elites displaced the classes who supported the economy and provided troops for the army. After Justinian’s reign, at the close of the sixth century, Mr. Brownworth writes that “the merchants, industrialists, and small landowners that made up the middle class were diminishing as wars and uprisings began to disrupt trade . . . small farms began to disappear, swallowed by the ravenous hunger of the great aristocratic landowners.” [p. 117] Centuries later, in 975, Emperor John I Tzimiskes returned from victories over the Muslims but discovered that the imperial chamberlain (a eunuch) was seizing all the land. He tried to stop him, but the chamberlain poisoned him first. [p. 205] Mr. Brownworth sees similar problems in the empire around 1025, when an “arrogant” and “insulated” educated class deliberately chose weak emperors, driving small farmers almost “to extinction” or serfdom, and spent so much they devalued the currency. [p. 221]

He writes that by 1347, “what was left of Byzantium was devolving into something resembling class warfare.” There were massacres of aristocrats and a pretender, John Cantacuzenus, even invited the Turks to fight for him. As a result, the Turks conquered Adrianople in 1362, the sultan sold the population into slavery, and eventually all Thrace filled with Turkish settlers. [p. 274]

It’s a more dramatic version of what we see today. Our elite is well-educated but not wise; prosperous, but not patriotic. The middle class, the bedrock of the nation, is weakening economically and socially. Elites use foreigners to win domestic power via replacement migration rather than as military auxiliaries. The consequences are the same.

Finally, there was a repeating pattern of trusting blindly in ideology or theology. The Eastern Roman Empire’s temporal power bolstered its spiritual power. Hagia Sophia’s beauty helped convert the Russians, the Bulgarians, and the Serbs. However, some emperors undermined their own legitimacy through religious persecution. In 725, Emperor Leo III gave a sermon explaining the rise of Islam by saying the Orthodox were using graven images. This unleashed a wave of persecution by emperors who thought that destroying Christian images would somehow help the Christian cause. It had no real-world objective beyond guessing the will of God.

Argument about icons before the emperor, from the Skylitzis Chronicle.

Similarly, the refusal of the western pope and the Byzantine patriarchs to work together ensured their own destruction. Just as there is one God, there can only be one emperor, the sword that will protect the church. However, unnecessary divisions between the Latin and Greek churches led the Pope to proclaim Charlemagne “Holy Roman Emperor” in the West. This undermined the legitimacy of the empire, the papacy, and ultimately of Christianity. Popes in the west became temporal leaders bullied by kings and constantly in search of protectors. Instead of remaining above power politics, popes were mired in the unseemly battles.

Meanwhile, in the east, the worse the situation became, the more stubbornly eastern Christians clung to independence. Mr. Brownworth argues that Christians in Egypt voluntarily surrendered to the first Islamic invaders partly because they were dissatisfied with rule by fellow Christians. They found that “their new masters” were “considerably less tolerant than the orthodox regime they had swept away, but by then it was too late.” [p. 133] The Arab invasions and the population changes that followed wiped out the Hellenized Middle East and North Africa. It is now part of the Islamic world. That is far more serious than any doctrinal dispute.

In the empire’s final days, emperors repeatedly went west to beg for help, only to be told that they must submit to Rome. Some did, but found that their own subjects angrily rejected them. Meanwhile, the West never truly awakened to the threat. Only a few Genoese fought with the Byzantines at Constantinople’s last stand. The West put more effort into sacking the city in the Fourth Crusade than in trying to save it.

Religious authority needs temporal power. When the desperate Byzantines fled to Hagia Sophia in the terrible final hours, no angels fulfilled the prophecy to rescue them. The Turks butchered priests at the altar. Today, Middle Eastern Christianity has been all but wiped out. Under the Tsars, Russia repeatedly tried to retake Constantinople but failed, partly because of opposition from Western powers.

A painting of one of the many sieges of Constantinople.

White traitors, myopic elites, and wishful thinking; Constantinople fell because the West failed to act as one. There will always be fights among whites. However, they are not potentially fatal conflicts where the stakes are the continuation of a people and a culture — rather than just an exchange of territory. Western kings never grasped the gravity of the alien threat. Just a few decades before the empire fell, Mr. Brownworth writes, “a concerted effort by Christendom just might have been able to push the Turks out of Europe while they were still fragmented,” but the “European powers” had “a false sense of security.” [p. 281]

It continues today. Demographic trends ensure whites will be minorities within our own countries within this century, even in Europe. Globally, we confront the rising power of China and an enormous African population boom. Few of “our” leaders fight for our race and civilization. “Our” rulers sometimes seem to be deliberately destroying us.

We should have faith in victory, but faith can’t be an excuse for inaction. What the West needs today are men who take the long view. We are doomed if we remain divided. Whites throughout the world share common foes and a common destiny.

The West is one. This won’t always mean political or religious unity. But it does mean that we see each other as comrades and family. It means that we can’t allow rulers who claim to speak in our name to set us at each other’s throats. We can’t afford another Fourth Crusade.

The fight that matters is the fight for our people. We must fight, not because we believe we are superior, but because we know we aren’t invincible. We see the cost of failure. We remember what has been lost in the Levant, northern Africa, Rhodesia, South Africa, and countless other beacons of civilization that have been snuffed out. Few torches remain. We will keep them lit and light new ones.

When Constantinople fell, its legacy lived on in the Renaissance, the Orthodox churches, and in Russia. Its light still shines because the West still lives. However, if we fail now, the darkness will last forever. We’re the heirs of Greece and Rome. That’s not a boast; it’s a challenge to live up to.