The Great Replacement: Philadelphia

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, November 20, 2020

(Image Credit: © Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press.)

This is the eighth in a series about the continuing disappearance of whites from American cities (see our earlier entries for Birmingham, Washington, D.C., New York City, Chicago, Richmond, Milwaukee, and Baltimore). Many people still pretend that The Great Replacement is a myth or a conspiracy theory, but the graphs that accompany each article in this series prove them wrong. Every city has a different story but all have seen a dramatic replacement of whites by minorities.

H.W. Brands’s biography of Benjamin Franklin called him “the first American.” Although he was born in Boston, Philadelphia was Franklin’s real home, and during his lifetime it was America’s first city. It was there that Franklin started America’s first subscription library, published the first American political cartoon, started the American Philosophical Society, the first fire department, and the first fire insurance company. It was in Independence Hall that Benjamin Franklin and the other Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia was the de facto capital during the Revolution (though Congress had to flee British forces).

Independence Hall in 2019. (Credit Image: Mys 721tx via Wikimedia)

Until 1790, Philadelphia was America’s largest city. After the Revolution, the Framers met again in Independence Hall and wrote the Constitution, which, whatever its failings, has been the most successful and stable governing document in history.

You can imagine America without Chicago, Detroit, or perhaps even New York. (New York was mostly in Loyalist hands during the Revolution). Only Boston can contest Philadelphia’s claim to be America’s first and indispensable city. Philadelphia is where we were born. Perhaps it is fitting that it seems to be where we are dying.

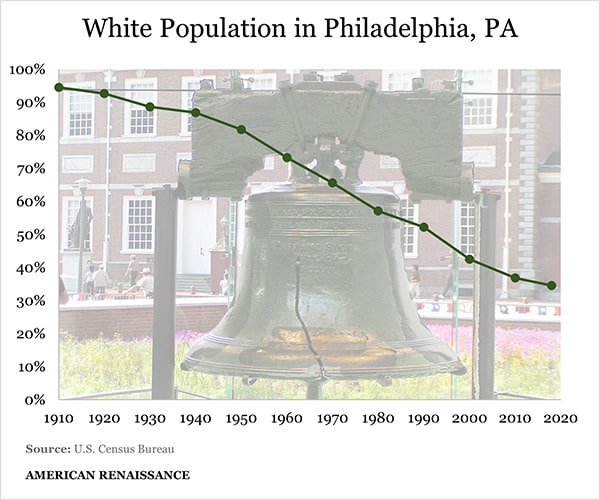

In this series on The Great Replacement in American cities, it’s rare to see steady decline. Before the Black Lives Matter riots, whites were moving back into many American cities, redeeming them from post-1960s collapse. However, Philadelphia has seen constant white exodus. In 1910, Philadelphia was 94.5 percent white. In 2018, Philadelphia was just 34.6 percent white. I have no doubt that after events since June, it will drop to less than a third in 2021.

Blacks were in Philadelphia as slaves even before American independence. However, the city instituted gradual emancipation, and 70 percent of Philadelphia’s blacks were free by 1783. In 1785, Benjamin Franklin became president of America’s first abolition society, based in Philadelphia. Blacks competed with whites for jobs, which led to occasional violence. Frederick Douglass wrote in 1848 that Philadelphia “more than any other [city] in our land, holds the destiny of our people,” but complained in 1862 that “there is not perhaps anywhere to be found a city in which prejudice against color is more rampant than Philadelphia.”

Many Philadelphia blacks fought for the Union. Philadelphia’s Camp William Penn trained about 11,000 black soldiers. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Mütter Museum recently unveiled a monument to black Union soldiers. (Mütter Musuem director Robert Hicks said that black soldiers often died from disease because doctors, “usually white, struggled to understand how black bodies differed from white ones.” This is a surprisingly frank acceptance of racial differences.)

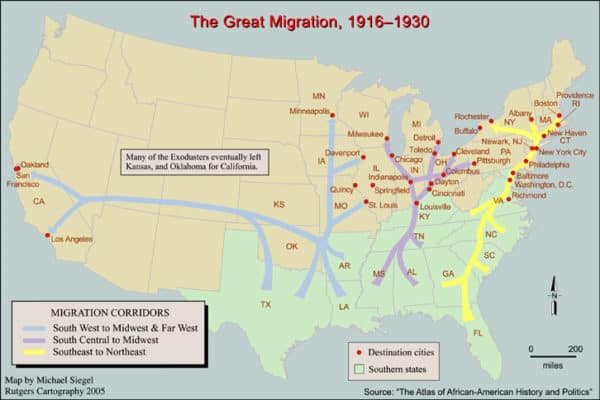

By the turn of the century, there were enough blacks in the city for W.E.B. Du Bois to write The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. He concluded that white people were responsible for blacks’ plight. Dramatic demographic change came with the Great Migration, as blacks moved north to fill labor shortages caused by the First World War. In 1916, the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Erie Railroad, and the B & O gave free passage to Southern blacks if they worked for the line. According to The Great Migration Project, 150 blacks a week came to Philadelphia between May 1916 and spring 1918, with the number rising to thousands a month in the summer of 1918.

Black organizations, including the NAACP and the “Negro Migration Committee,” helped settle newcomers. According to the website Philly History.org, which uses city archives, the black population grew rapidly:

1910: 84,459

1920: 134,224

1930: 219,599

1940: 250,000

Robert Gregg’s Sparks from the Anvil of Oppression: Philadelphia’s African Methodists and South Migrants, 1890-1940, says:

White Philadelphians began to separate themselves from their black neighbors in all spheres, separating not only housing, but accommodations, services, education, and religion. Black people were barred from all center-city restaurants, hotels, lunch counters, dime store counters, and theaters.

Even racially integrated churches split, and during the Second World War, whites resisted letting blacks join the workforce. In 1944, white workers went on a “wildcat strike” to protest skilled-job training for blacks at a trolley company. President Roosevelt had to send in the army. The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia calls this a “hate strike.”

Blacks’ political power grew with their numbers. In 1942, the NAACP joined the “Fellowship Committee” that was supposed to help “civil rights” movements, and after the war, Philadelphia passed several laws to help blacks. In April 1951, the city banned racial and religious discrimination in all city jobs and set up the Philadelphia Commission on Human Rights to enforce the bans. The Commission also tried to put more blacks in building trades. The federal government got involved in the 1960s, with President Richard Nixon’s “Philadelphia Plan,” which imposed racial quotas. This evidently didn’t do enough. In 2019, a Philadelphia Inquirer headline read, “City’s lack of diversity in building trades persists.”

The most important black activist in the modern era was the native Philadelphian and lawyer Raymond Pace Alexander, who desegregated schools and other institutions. In 1951, he won a seat on the city council before eventually becoming the first black judge on the Pennsylvania Courts of Common Pleas. Philadelphia was progressive by the standards of the time, but it had the same problem as other Northern cities: Blacks kept fighting with police and accusing them of brutality. This culminated in the devastating 1964 race riot — one that began with fake news.

Raymond Pace Alexander

On August 28, two police officers, one white and one black, approached a black couple, Rush and Odessa Bradford, who were having a “domestic dispute” and were holding up traffic. The couple argued with the cops, the black officer pulled Odessa out of the car to arrest her and she bit him. Nearby blacks then attacked the officers.

This gave rise to a rumor (supposedly started by Raymond Hall, a “neighborhood agitator”) that police had killed a pregnant black woman. Blacks began smashing shops on Columbia Avenue and police pulled back. The riots lasted three days.

Time magazine wrote:

The blame could not even be placed on both races, since the riot was all-Negro and it was unprovoked by any incident that could conceivably be considered a “civil rights violation.” Philadelphia has worked hard to eliminate friction between Negroes and police. It was one of the few cities with a civilian review board to handle complaints of police brutality.

At the time, Philadelphia’s police department was about 20 percent black, but it could not prevent two deaths and millions of dollars in property damage. Whites moved out of Philadelphia, as they did from many cities in the 1960s. By 1970, Philadelphia was less than two-thirds white. However, whites who remained had a law-and-order champion: Frank Rizzo.

Frank Rizzo

After more than 24 years in the Philadelphia police department, Rizzo became commissioner in 1967. Known affectionately as the “The General” by some officers, Rizzo tried to fight a dramatic rise in murders after 1965. He became mayor from 1972 to 1980.

Rizzo’s populist style was like Donald Trump’s, and his supporters showed him the same devotion. The city put up a statue of Rizzo in 1998, but this year, the city took it down and removed a mural of Rizzo after BLM protests. Vandals had already defaced them.

The Frank Rizzo Mural in Italian Market before it was destroyed. (Credit Image: Bohemian Baltimore via Wikimedia)

Philadelphia Mayor and Police Chief Frank Rizzo, in Philadelphia, PA. Removed by the city on June 3. (Credit Image: RegBarc via Wikimedia)

Frank Rizzo fought MOVE, a curious group that fused black nationalism and anarcho-primitivism. (MOVE was not an acronym; members greeted each other with “On the MOVE.”) Members lived communally in Philadelphia, but neighbors complained they left garbage in the streets and screamed vulgar political messages through a megaphone. MOVE violated the health code and the city tried to evict it, but armed members barricaded themselves inside.

In 1978, police and firefighters stormed the building and a firefight began. Then-police commissioner Joseph O’Neill and Mayor Rizzo claimed MOVE shot first; officer James Ramp died with a shot in the head. Nine MOVE members were convicted of murder.

Although Frank Rizzo has become a symbol of police repression, he wasn’t the man who ordered the most notorious police action against MOVE. In 1984, Wilson Goode defeated Rizzo in a primary and became Philadelphia’s first black mayor. Goode declared MOVE a “terrorist organization,” and on May 13, 1985, police again ordered activists who were violating the law to leave the house. After a firefight, Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor (a white man) ordered police to drop two one-pound “entry-device” bombs on a bunker on the roof of the house. A fire broke out and killed 11 people, including five children. Officer Frank Powell, who dropped the bombs with “perfect” placement, has said he “never” regretted what he did.

Former mayor Goode says there was a “conscious” decision to let the fire burn, but there is a dispute over who made the decision. In 1996, a jury held former fire commissioner William Richmond and Police Commissioner Sambor personally liable, though they only had to pay one dollar a week to the last survivor of the bombing and various relatives. The city of Philadelphia paid more than $1.5 million.

Philadelphia Mayor W. Wilson Goode at a press conference to discuss the aftermath of the bomb and fire that destroyed the MOVE house. (Credit Image: Leif Skoogfors/CORBIS)

Philadelphia has just apologized for the MOVE bombing. Why now? The MOVE bombing is hardly unknown, especially after the 2013 documentary Let It Burn. However, it wasn’t especially relevant. From 1990 until fairly recently, the number of murders dropped, as it did in other big cities. In 2017, City Life reported that crime in Philadelphia was at its lowest level in decades. Black Lives Matter probably explains why MOVE is getting new attention.

There seems to be another reason. On October 26, police responded to a domestic violence call. Walter Wallace Jr., a black man with a long criminal record and eight children, was reportedly attacking his family. He was an “aspiring rapper” who made songs about shooting police. He was also awaiting trial for threatening to shoot a woman. Bodycam footage shows Wallace holding a knife. Police retreat and tell him 11 times to drop it. He keeps advancing, gets too close, and police shoot him. There will be a wrongful death suit.

Protests over Wallace’s death turned into several days of riots. Rioters injured 30 police officers; the National Guard restored order. Philadelphia City Council member Jamie Gauthier said, “[W]e can connect what happened to MOVE with what we saw happen with Walter Wallace Jr.” After the riots, the Philadelphia City Council passed an ordinance banning tear gas, rubber bullets, and pepper spray to control rioters. The Council is considering a bill that would ban police from stopping people with “minor” driving violations like a broken taillight.

As they are almost everywhere, Philadelphia police are pulling back and blacks are more defiant. In August 2020, a local news affiliate reported that the city’s murder rate was now second only to Chicago’s. Earlier this week, Fox News reported that Philadelphians shot more than 1,600 people so far this year, that more than 230 homicides were not solved as of October, and that the number of murders is up by 41 percent. The city already has exceeded 2019’s murder count by almost 100. Even before Wallace’s death, an average of three children were being shot every week.

Philadelphia police wait outside a row house in West Philadelphia, the site of a multiple homicide, on Nov. 19, 2018. (Credit Image: © TNS via ZUMA Wire)

Just before Wallace’s death, there was an attempt to set up a pseudo “autonomous zone” on Benjamin Franklin Parkway, just as protesters did in Seattle. Police found a van with explosives on the parkway two weeks ago and arrested two blacks. They planned to blow up ATMs but to make it look like protest. In the words of Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro, they wanted to “use a message of justice to provide cover for their own gain.”

One wonders what Ben Franklin would have made of this. The City of Brotherly Love is becoming another white-minority ruin. If Philadelphia is the key to America’s past, it is also a preview of our future as a minority. Benjamin Franklin supposedly said we had a Republic, if we could keep it. Our rulers are giving it away.