American Slave Insurrections

Neil Kumar, American Renaissance, October 23, 2020

(Credit Image: © Fox Searchlight Pictures/Entertainment Pictures/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Auribus teneo lupum, nam neque quomodo a me amittam invenio neque uti retineam scio.

“I hold the wolf by its ears, for I neither know how to get rid of her, nor yet how to keep her.” – Terrence, c. 165 BC

Race relations in the 13 colonies and the later United States of America is a story of deep antagonism. This truth seems obvious today, and Americans from the settlement of Jamestown until the “Civil Rights movement” understood that truth. Americans before the Civil War understood it best; they had to deal with slave uprisings.

Records about antebellum slave insurrections are scarce. Whites generally suppressed reports of servile insurrection because they didn’t want to encourage other slaves, so many of the rebellions we know about were the ones too large to censor.[i] Slaves tried to revolt hundreds of times in the antebellum period. The first settlement within the present-day United States had a slave revolt. San Miguel de Gualdape — established by Spaniards in what is now Georgia in 1526 — failed in just a few months, due to shipwreck, hunger, cold, disease, hostile Indians, and a slave rebellion.[ii]

Evidence suggests that black slaves were often disaffected and rebellious.[iii] Mass insurrections were rare, but abortive attempts and conspiracies were common, as were other forms of resistance. Sometimes slaves would steal. They also worked slowly, sabotaged machinery, and carelessly or deliberately destroyed crops, fences, and tools. They neglected animals.[iv]

Blacks often tried to kill their masters,[v] and the preferred methods were arson and poison. Arson was so common that it raised insurance premiums. Entire towns could be lost to the torch.[vi] In the 1790s, prominent citizens of Charleston, South Carolina, organized a committee to ensure that brick or stone be used in building new buildings instead of wood, making them harder to burn. Servile arson also encouraged construction of fire-escapes, which became common in 19th-century Virginia.[vii]

Newspaper reports from the time show poisoning was also common. In 1751, South Carolina ordered the death penalty for slaves who tried to poison whites, and the guilty would not receive benefit of clergy. The preamble to this legislation explained that it was necessary because the crime was attempted so often.

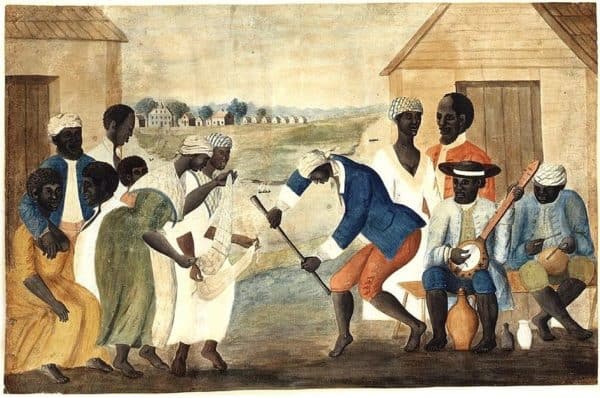

The Old Plantation

A decade later, the Charleston Gazette said that “the negroes have again begun the hellish practice of poisoning.” In 1770, Georgia passed a law identical to that of South Carolina.[viii] In 1740, slaves in New York City tried to exterminate whites by poisoning the water supply. Citizens were so frightened that they bought spring water from street vendors, showing “how strong was the suspicion and fear of the approximately two thousand slaves among the ten thousand white inhabitants of the city.”[ix]

Fugitives slaves, or maroons, also harassed whites. They formed loose bands and communities, and preyed on whites, plundering plantations and robbing travelers. Maroons “plagued every slave society in which mountains, swamps, or other terrain provided a hinterland into which slaves could flee.”[x]

Occasionally, maroons made alliances with American Indians; the Florida Seminole Wars are the best example.[xi] In 1823, maroons in Norfolk County, Virginia, killed several whites, and one terrified citizen wrote: “[N]o individual after this can consider his life safe from the murdering aim of these monsters in human shape. Everyone who has haply rendered himself obnoxious to their vengeance, must, indeed, calculate on sooner or later falling a victim.”[xii] Until the final days of the Confederacy, Southerners sought out and suppressed maroons.[xiii]

Insurrections could involve any number from a dozen to several thousand slaves. On most occasions, authorities discovered conspiracies and smashed them. When this failed, insurrections had one main purpose: to slaughter as many whites as possible. The most murderous insurrection killed nearly 60 whites.[xiv] Here are some of the most significant revolts.

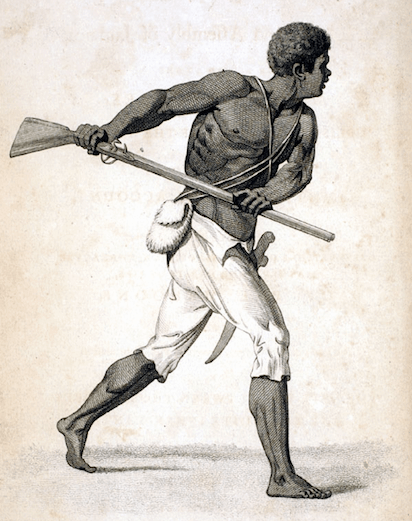

Detail from Maroon Leader, 1796.

In 1712, a band of around two dozen slaves and Indians in New York City got hold of guns, swords, knives, and axes. Early one Sunday morning, one of the insurrectionists set fire to his master’s plantation while others hid in the dark as local whites arrived to douse the blaze. Blacks ambushed and killed at least nine.[xv]

This incident was partially responsible for the intense fear that surrounded another servile conspiracy in New York City three decades later. In early 1741, several mysterious fires broke out in the city. Residents saw blacks running from some of these fires, and suspected insurrection, not random arson.

Authorities traced the plot to a disreputable bar on Crown Street, where the lower-class whites socialized with blacks. The plan, according to several conspirators, was “to destroy, root and branch, all the white people of this place, and to lay the whole town in ashes.”[xvi] At the trial of the white co-conspirators, the judge marveled at whites who proclaimed themselves Christians but who would make “negro slaves [not only] their equals, but even their superiors, by waiting upon, keeping with, and entertaining them with meat, drink, and lodging, and, what is much more amazing, to plot, conspire, consult, abet, and encourage these black seed of Cain to burn this city, and to kill and destroy us all.”[xvii] The judge sentenced the whites to death.

The conspiracy was led by African-born slaves and was said to have involved 30 or 40 blacks. The insurrectionists “called for a war on the Christians in a manner suggestive of the early Caribbean Obeahmen [witch doctors] and foreshadowing the call to arms of the Vodûn priests of Saint-Domingue.”

African-born slaves also led the 1739 insurrection near the Stono River in South Carolina.[xviii] The only eyewitness account of that event, the bloodiest insurrection in South Carolina, was that of Lieutenant-Governor Lawrence Bull. Returning to Charles Town from Granville County on horseback, Bull happened upon a band of 80 or so blacks, carrying guns and flags and chanting, “Liberty!” Bull rode off and notified the militia.

The site of the Stono Slave revolt. (Credit Image: ProfReader via Wikimedia)

The black leader was an illiterate slave named Jemmy (also known as Cato). The rebels decapitated their first two white victims, and displayed the heads on a staircase. The blacks then sacked several plantations, plundered liquor stores, and killed whites.[xix] By the time the insurrection was put down, slaves had razed a dozen plantations and killed and at least 25 white men, women, and children.[xx]

Many contemporary sources blame Spanish agents for the insurrection. Lieutenant-Governor Bull told his superiors in London that the Stono revolt had been instigated by a Spanish proclamation issued from St. Augustine offering “freedom to all negroes who should desert . . . from the British Colonies.” In 1738, two different bands of slaves in the region escaped their plantations to head for what they hoped would be freedom in Spanish Florida. One of them, passing through Georgia, murdered several whites.[xxi] Some time after the Stono insurrection, a Spanish agent was arrested in Georgia with instructions to foment “a general insurrection of negroes” in the British South. This charge was made against Spain well into the 19th century.[xxii]

Gabriel Prosser marked the turn of the nineteenth century with a vast plot in Henrico County, Virginia. He was literate, willful, stood six feet two or three inches tall, and was considered by both blacks and whites as “a fellow of great courage and intellect above his rank in life.”[xxiii] In the spring of 1800, slaves in Virginia quietly made crude swords and bayonets, and hundreds of bullets. About one thousand — some mounted — armed with clubs, scythes, homemade swords and bayonets and a few guns, gathered six miles outside of Richmond. However, a downpour delayed their invasion of the city. Word got out about the insurrection, and Governor James Monroe of Virginia posted artillery and called up 650 militiamen. Before the slaves could attack, authorities arrested any they could identify.

James Monroe

Governor Monroe interviewed Prosser, noting that “from what he said to me, he seemed to have made up his mind to die, and to have resolved to say but little on the subject of the conspiracy.” John Randolph, who saw several of the blacks in custody, wrote: “[The slaves] have exhibited a spirit, which, if it becomes general, must deluge the Southern country in blood. They manifested a sense of their rights, and contempt of danger, and a thirst for revenge which portend the most unhappy consequences.”

Mississippi Territorial Governor W.C.C. Claiborne suggested that 50,000 slaves may have been in on the plot; others estimated their numbers at between two and 10 thousand. Governor Monroe believed that the plot had reached Virginia’s entire slave population.[xxiv] The blacks had decided to spare all Frenchmen, Methodists, and Quakers whom they considered sympathetic to emancipation. They would kill all others, but show mercy to whites who agreed to emancipation — by only cutting off an arm.[xxv]

W.C.C. Claiborne

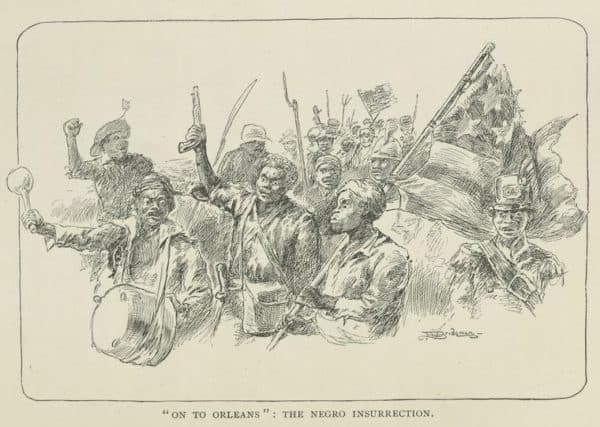

In 1811, there was a large insurrection in Louisiana. It began when the ringleader, together with two dozen subordinates, hacked his master’s son to death as he slept. The boy’s father escaped and sounded the alarm.[xxvi] Panic set in:

It was pouring rain in New Orleans on the morning of January 9, 1811, and the road running into the city was quickly transformed into thick mud that sucked in horse hooves, carriage wheels, and human feet alike. The miserable weather contributed to the traffic jam, stretching as far as nine miles, of frantic planters, along with their families and servants, who were fleeing their plantations for the safety of the city. As one observer described it, the road to New Orleans ‘for two or three leagues was crowded with carriages and carts full of people, making their escape from the ravages of the banditti—negroes, half-naked, up to their knees in mud with large packages on their heads driving along toward the city.’[xxvii]

As many as 500 slaves, led by a free mulatto from Saint-Domingue and armed with axes, clubs, knives, and a few firearms, marched on New Orleans. They sacked plantations, intent on “killing every white they could get their hands on.” Local planters and militiamen took action, but the slaves were not fully subdued until Governor Claiborne called out the full militia. Brigadier-General Wade Hampton led 400 militiamen and 60 U.S. Army soldiers, joined by 200 soldiers from Baton Rouge, to destroy the insurrection.[xxviii]

In 1822, in Charleston, South Carolina, Denmark Vesey led what Thomas Higginson, Unitarian minister and member of the Secret Six (the group of wealthy Northern abolitionists who financed John Brown’s attack at Harper’s Ferry), called “the most elaborate insurrectionary plot ever formed by American slaves.” Vesey’s conspiracy involved thousands of slaves who planned to exterminate every white in Charleston, seize bank reserves, and sail to Haiti.[xxix] One of the black leaders reportedly remarked that the men “would know what to do with the white women.”[xxx] Their plan was ambitious, with simultaneous attacks from five directions and a sixth force on horseback to patrol the streets.[xxxi]

Slaves within the city were set to start fires and set explosions with stolen black powder. When whites ran out of their homes to put the fires out, the blacks were to slaughter them. In the chaos, columns of slaves would fall upon the city from every direction, seizing the state and federal arsenals. Preparations were elaborate:

The negroes had made about 250 pike-heads and bayonets and over three hundred daggers. They had noted every store containing any arms and had given instructions to all slaves who tended or could get horses as to when and where to bring the animals. Even a barber had assisted by making wigs and whiskers to hide the identities of the rebels. Vesey had also written twice to St. Domingo telling of his plans and asking for aid. All who opposed were to be killed. [xxxii]

The plot failed and the authorities sentenced Vesey to death. On the day of his execution, federal soldiers were called to help the militia suppress another insurrection.[xxxiii] The fact that Vesey was a free black, rather than a slave, “sent shockwaves throughout Charleston’s white community, the members of which had always considered the free blacks living in their midst to be a nonthreatening, although unwelcome, presence.”[xxxiv] Though Vesey and his subordinates had maintained lists of their co-conspirators, only one list and part of another were recovered. One witness testified that nearly 7,000 slaves had been involved, while another implicated 9,000.

The Denmark Vesey Monument in Hampton Park in Charleston, South Carolina. (Credit Image: MsBJPeart via Wikimedia)

In 1831, Nat Turner led the deadliest slave revolt in American history, in Southampton County, Virginia. Thomas Gray, the lawyer for several of the slaves involved in the revolt and the man who published Turner’s confession, wrote that the insurrection “was not instigated by motives of revenge or sudden anger, but the results of long deliberation, and a settled purpose of mind.” Gray continued: “It will thus appear, that whilst everything upon the surface of society wore a calm and peaceful aspect; whilst not one note of preparation was heard to warn . . . of woe and death, a gloomy fanatic was revolving in the recesses of his own dark, bewildered, and overwrought mind, schemes of indiscriminate massacre to the whites.”[xxxv] Virginia had a white majority, so any rebellion was sure to be suicide.[xxxvi]

Around two in the morning, Turner and fellow conspirators broke into the cider press and got drunk. Turner later acknowledged that, as the leader, “I must spill the first blood.” He crept up to his master’s house with his men and took a hatchet to his master’s head.[xxxvii] Turner later recalled that “the murder of this family, five in number, was the work of a moment . . . there was a little infant sleeping in a cradle, that was forgotten, until we had left the house and gone some distance, when Henry and Will returned and killed it.”[xxxviii] Ironically, Turner later admitted that he had had a kind master and that he had “no reason to complain of his treatment of me.”

The slaves fanned out across the countryside and marched house to house, killing every white they found. The slaughter continued well into the next day; as the death toll mounted, so too did Nat Turner’s band. By the end, he had about 60 slaves, “all mounted and armed with guns, axes, swords and clubs.” At one home, the family tried to barricade the door. Turner later explained:

Vain hope! Will, with one stroke of his axe, opened it, and we entered and found Mrs. Turner and Mrs. Newsome in the middle of a room, almost frightened to death. Will immediately killed Mrs. Turner, with one blow of his axe. I took Mrs. Newsome by the hand, and . . . struck her several blows over the head, but not being able to kill her, as the sword was dull. Will, turning around . . . dispatched her also.[xxxix]

When Turner arrived at the Whitehead family’s home, he said he was:

[Ready] to commence the work of death, but they whom I left, had not been idle; all the family were already murdered, but Mrs. Whitehead and her daughter Margaret. As I came ‘round to the door, I saw Will pulling Mrs. Whitehead out of the house, and at the step he nearly severed her head from her body, with his broad axe. Miss Margaret. . . had concealed herself. . . on my approach, she fled, but was soon overtaken, and after repeated blows with a sword, I killed her by a blow on the head, with a fence rail.

Turner remembered details:

I sometimes got in sight in time to see the work of death completed, viewing the mangled bodies as they lay, in silent satisfaction, and immediately started in quest of other victims. Having murdered Mrs. Waller and ten children, we started for Mr. William Williams’, having killed him and two little boys that were there; while engaged in this, Mrs. Williams fled and got some distance. . . but she was pursued, overtaken, and compelled to get up behind one of the company, who brought her back, and after showing her the mangled body of her lifeless husband, she was told to get down and lay by his side, where she was shot dead.

There was a school at the Waller house, where Nat Turner’s army killed 10 children. An 11th girl managed to escape and hid in the swamp, where she was discovered days later, terrified and whimpering.

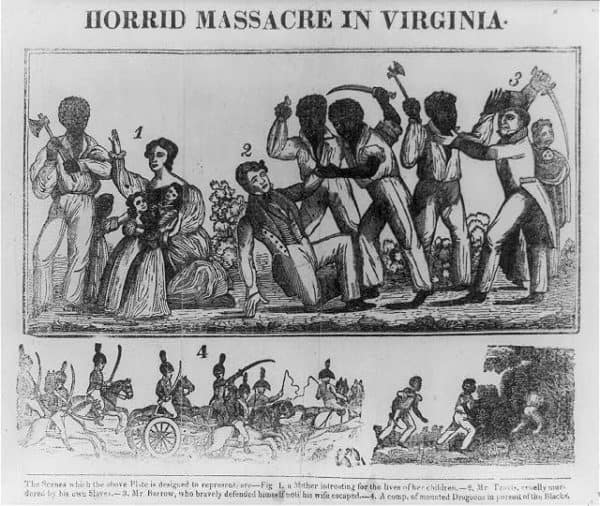

Composite of scenes of Nat Turner’s rebellion. (Image from Authentic and impartial narrative of the tragical scene which was witnessed in Southampton County, 1831 via the Library of Congress.

John Baron, “discovering them [the slave rebels] approaching his house, told his wife to make her escape, and, scorning to fly, fell fighting on his own threshold.” He fired his rifle and then used it as a melee weapon but was “overpowered and slain.” The slaves’ lawyer Thomas Gray wrote of Baron: “His bravery, however, saved from the hands of these monsters, his lovely and amiable wife . . . . As directed by him, she attempted to escape through the garden, when she was caught and held by one of her servant girls, but another coming to her rescue, she fled to the woods, and concealed herself.”[xl]

On the third day, three companies of federal artillery arrived at Southampton — with seamen from two warships in the Chesapeake — and put down the insurrection. Turner and his men had killed at least 57 men, women, and children in a 20-mile-wide swathe.[xli]

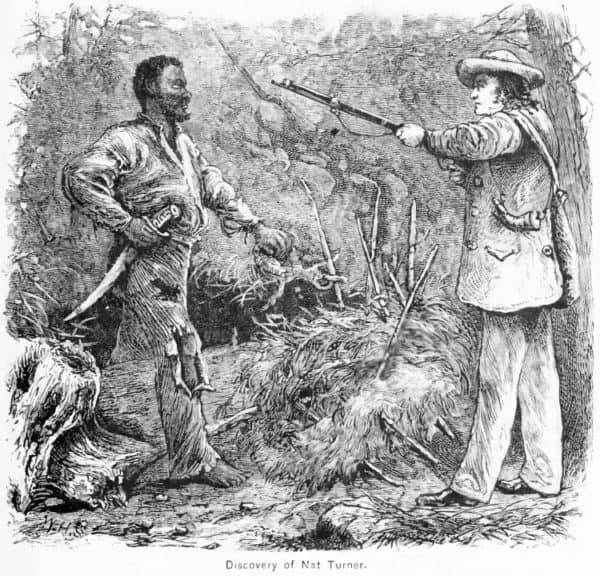

Discovery of Nat Turner by William Henry Shelton. (Image via Wikimedia)

Mrs. Lawrence Lewis, a niece of George Washington, wrote of the Turner rebellion: “[I]t is like a smothered volcano — we know not when, or where, the flame will burst forth, but we know that death in the most horrid forms threaten us. Some . . . have become deranged from apprehension since the South Hampton affair.”[xlii]

Though written after a different conspiracy, one New Orleans editorial could easily have been written about the Turner rebellion: “[E]nmity between the white and black race is rapidly maturing.” The recurrent “attacks of the negro upon the white man in our city . . . should excite our suspicions, whether they be not the piquet guard of some stupendous conspiracy among the blacks to fall upon us unawares.” The editorial continued with a warning: “Let us always be on our guard, and grant no indulgences to the negro, but keep him strictly within his sphere.” [xliii]

One slave insurrection succeeded: a mutiny aboard the slave transport Creole in 1841. One black and one white were killed in the mutiny, after which the blacks forced the white navigator to sail to the British Bahamas. Most of the blacks escaped to freedom.[xliv]

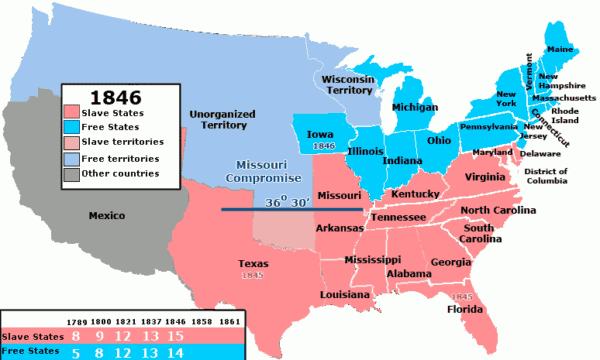

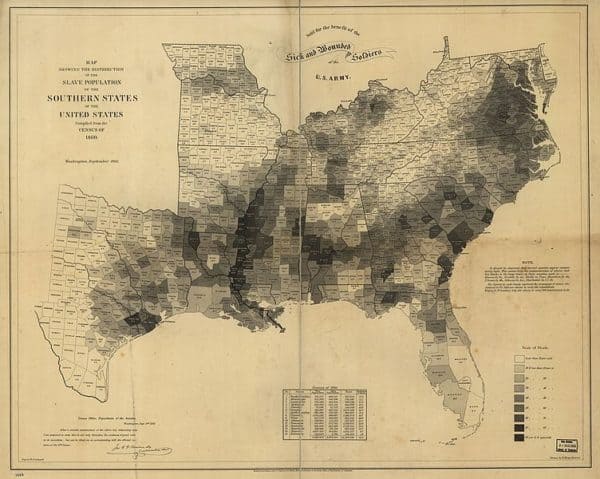

Slave insurrections were most frequent where the black population was greatest.[xlv] The countries of the New World most plagued by insurrection had a high ratio of blacks to whites. In British Guinea, slaves were 90 percent of the population. Jamaica, Saint-Domingue, and the rest of the Caribbean had black majorities of over 80 percent.

For this reason, in the United States, slaveholders did their best to maintain white majorities. In 1860, blacks were a majority only in South Carolina and Mississippi, where their proportion ranged from 55 to 57 percent. Blacks approached half the population in Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia, and made up between 20 and 30 percent of the other slave states. No more slaves were being imported by this time. After what happened to Saint-Domingue, whites knew the dangers of a large black majority.[xlvi]

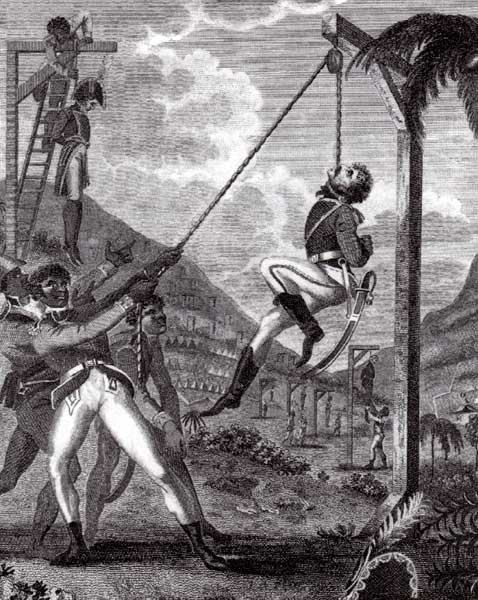

Blacks lynch a French soldier during the Haitian Revolution.

At the time of the 1739 Stono Rebellion, South Carolina whites were heavily outnumbered by slaves. In 1737, it was estimated that the colony could muster no more than 5,000 fighting men, as opposed to 22,000 slaves.[xlvii] At the time of Nat Turner’s rebellion, Southampton County, Virginia, had about 6,500 whites and 9,500 blacks.[xlviii]

As for weapons, large numbers of slaves had access to axes. Slaves who worked in the sugar fields carried knives large enough to decapitate a man with one blow, and every slave who worked in the tobacco fields carried a blade. Many slaves knew how to use firearms despite legal restrictions. As one former slave recalled, “culled folks been had guns all their life. They kept them hid.”[xlix] Planters often let favored, trusted slaves hunt with guns. Some slaves carried rifles and stood guard at plantations. Many of the bloodiest insurrections were led by favored, privileged slaves.

Why were there not more insurrections? One historian explains:

Even with some guns, the slaves faced overwhelming odds. The whites . . . of the plantation districts, the upcountry, and the backcountry raised their sons to shoot. Sharpshooting and extraordinary feats with arms became elementary marks of manhood. The white population constituted one great militia — fully and even extravagantly armed, tough and resourceful.[l]

Southern settlers and militiamen could also count on military garrisons,[li] there were few absentee landlords as was common on Saint-Domingue, and there was no vast hinterland to sustain maroon communities. The small-scale, dispersed nature of antebellum slavery also discouraged mass insurrections.[lii] Nevertheless, as one historian explains, “general risings of thousands, such as those in Jamaica, Demerara, and Saint-Domingue, or even of hundreds such as those in many countries, remained a possibility, which, however slim, rendered the hopes of a Gabriel Prosser, a Denmark Vesey, or a Nat Turner rational.”[liii]

Division among whites could spark an insurrection.[liv] The 1712 New York City uprising may have taken advantage of lingering divisions among white colonists that was related to the English Civil War and that led to Leisler’s Rebellion in New England. In South Carolina, hostile Indians and black maroons might help slaves rebel. Black slaves also knew about the national divisions between whites and how to exploit them. The slaves in the Stono insurrection knew the Spanish were offering freedom to runaway slaves from the English colonies.[lv]

Slaves were an effective weapon — a fifth column of sorts — in imperial intrigues. European powers frequently incited the slaves of rival colonies to revolt. In the fall of Saint-Domingue, “the ruling class split asunder” and Toussaint Louverture played the Spanish, French, and English against each another as he assembled the army that would eventually kill every Frenchman in Haiti.[lvi] Dessalines, the black leader responsible for the last mass murder of whites, was reportedly urged by the British to murder the French.[lvii]

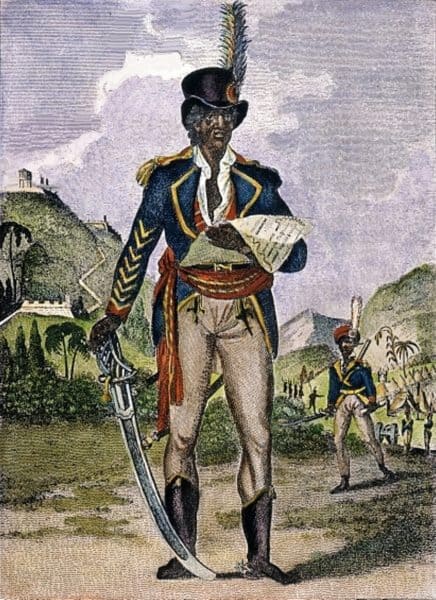

Toussaint Louverture

Gabriel Prosser’s 1800 conspiracy took place against the backdrop of an undeclared war with France, leading Prosser to expect French help. The bitter political division between Federalists and the Republicans, especially over the French Revolution, “made a deep impression on the slaves, who may well have thought that they saw a white nation on the verge of civil war.”[lviii]

France had abolished slavery in 1794 (Napoleon reestablished it), and after Prosser’s conspiracy, an editorial in the Fredericksburg Herald declared: “[I]t is very certain from all that has been discovered, that this dreadful conspiracy originates with some vile French Jacobins, aided and abetted by some of our own profligate and abandoned democrats. Liberty and equality have brought the evil upon us.”[lix]

Some blacks, especially those who were free, had a sophisticated understanding of politics. Denmark Vesey’s failed 1822 insurrection took place just after the protracted Missouri controversy. Vesey and his followers had carefully followed the debate. The conspirators had “firm evidence that antislavery sentiment was rising and that the slaveholders were being thrown on the defensive.”[lx] Vesey hoped that Northern whites would come to his aid.

Nat Turner made his move in 1831 after a tense constitutional convention in Virginia. The counties that would eventually become West Virginia demanded abolition and colonization (sending blacks back to Africa).[lxi] Ironically, Turner’s massacre united Southern whites as never before, as “whites of all classes effectively closed ranks against the slaves.”[lxii]

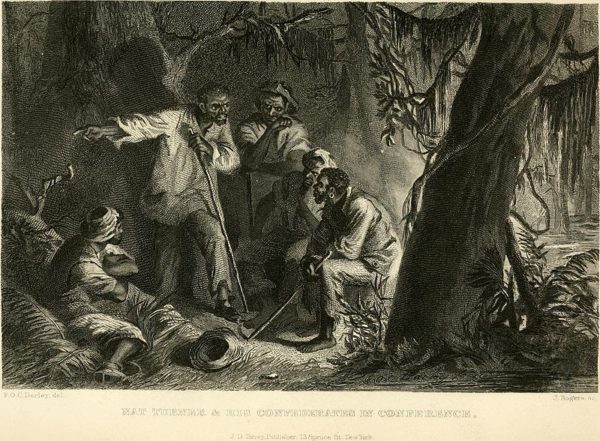

Nat Turner and His Confederates in Conference

There was widespread concern over the possibility of slave insurrection during colonial and American military campaigns, such as the war with the Dutch in Virginia in 1673, early Indian Wars in South Carolina in the late 1720s, the French and Indian War, the War of Independence, the War of 1812, the Texian Revolution, the Mexican War, and, of course, the War Between the States.[lxiii]

Fears of servile revolt were so serious that they affected Confederate troop movements.[lxiv] Throughout the war, there were steady reports of conspiracies and individual acts of sabotage, arson, and murder. Maroons dramatically increased their depredations. In several cases, white deserters and escaped Yankee prisoners formed biracial groups of bandits who preyed on lightly-defended Southerners while the Confederate Army was away fighting.[lxv]

According to James Gilmore, a wealthy merchant and emancipationist, in 1860 there was a large secret society of insurrectionary slaves in South Carolina. One told Gilmore that the South would be defeated in the coming War: “‘[C]ause you see dey’ll fight wid only one hand. When dey fight de Norf wid de right hand, dey’ll hev to hold de nigga wid de leff [sic].”[lxvi] Frederick Olmsted said that “any great event having the slightest bearing upon the question of emancipation is known to produce an ‘unwholesome excitement’” among the slaves.

On some occasions, unusual events that had no apparent connection with slavery were interpreted by blacks as harbingers of emancipation.[lxvii] The “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” campaign of 1840, in which each side denounced the other as “abolitionist,” raised false hopes among blacks in Alabama.[lxviii]

Another common factor in many conspiracies was white abolitionist agitation. Nat Turner’s 1831 rampage was a turning point in antebellum America because Northern abolitionists, including radical clergymen, could plausibly be blamed for inspiring it.[lxix] In his December legislative message, Virginia Governor John Floyd hinted darkly that the plot was “not confined to the slaves,” and that the animating spirit “had its origin among, and emanated from, the Yankee population,” with the slaves learning abolitionist doctrine from “Yankee peddlers and traders.”[lxx]

Virginia Governor John Floyd

Governor Floyd had reason to believe this. “[H]orrified as Southern whites were by the uprising, some Northerners . . . could hardly suppress their satisfaction at what they took to be a justified rebellion against the horrendous institution of slavery.”[lxxi] As news of the Turner insurrection spread, so too did slave disturbances across the South. Governor Floyd was “fully convinced that every black preacher in the whole country east of the Blue Ridge, was in [on] the secret,” and that, “to the extent of the insurrection, I think it greater than will ever appear.”[lxxii]

Then-senator Jefferson Davis argued that servile insurrections were rarely initiated by blacks alone, but with the help of white abolitionists, and Southern authorities worked hard to prevent propaganda from reaching slaves.[lxxiii] In his seventh annual message in 1835, a year of many slave conspiracies, President Andrew Jackson demanded that Northern agitators stop sending propaganda to the South that was “calculated to stimulate them to insurrection and to produce all the horrors of servile war.”[lxxiv] With varying levels of certainty, authorities implicated whites in dozens of insurrectionary conspiracies, many of which involved mass slaughter.[lxxv]

An 1853 conspiracy in New Orleans that was said to have involved some 2,500 slaves was blamed on the activities of “malicious and fanatical” whites, “cutthroats in the name of liberty — murderers in the guise of philanthropy.”[lxxvi] In 1856, whites were implicated in a plot involving the slaves of three counties in southeastern Texas. In preparation for the bloodshed, the blacks “killed off all the dogs in the neighborhood” so they could not sound the alert.[lxxvii]

Southerners had good reason to blame egalitarian propaganda and even American Revolutionary war slogans about liberty and freedom.[lxxviii] In 1862, Bishop Elliot of Savannah, Georgia, wrote that after the War of Independence, the American people had:

declared war against all authority . . . . The reason of man was exalted to an impious degree and in the face not only of experience, but of the revealed Word of God, all men declared equal, and man was pronounced capable of self-government . . . . Two greater falsehoods could not have been announced, because the one struck at the whole constitution of civil society as it had ever existed, and because the other denied the Fall and corruption of man.

Southern leaders were aware of where Jeffersonian rhetoric could lead. To some, the Declaration of Independence “became but the mouthings of an irresponsible and dangerous fanatic, a ridiculous, high-sounding concoction of obvious absurdities.”[lxxix] Southern Federalists attacked the Republicans for their “French gospel of liberty, equality, and fraternity that the slaves would hear, interpret with deadly literalness, and rally around,” and it became increasingly common for whites to keep blacks far away from Fourth of July orations.[lxxx] Reverend C.F. Sturgis of South Carolina wrote that “their weak minds are liable to be led astray — the plainest things are likely to be perverted or exaggerated.”[lxxxi] It is probably no coincidence that the Fourth of July was often picked as the date to launch insurrections, or that Denmark Vesey had originally chosen Bastille Day.[lxxxii]

Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner all appealed to the Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man.[lxxxiii]

Some white refugees from Saint-Domingue spread across the Caribbean, to the northern coast of South America, and to the American South, especially South Carolina and Louisiana. They brought slaves with them. Their slaves “had seen and heard much during the revolutionary conflagration, and everywhere they became carriers of new doctrines” and played a part in many insurrectionary conspiracies.[lxxxiv] In 1800, Representative Rutledge of South Carolina told Congress that the slaves had already heard “this newfangled French philosophy of liberty and equality.” In the aftermath of the Vesey conspiracy, Edwin Clifford Holland noted the rhetorical significance of the French Revolution: “Let it never be forgotten that our negroes are freely the Jacobins of the country; that they are the Anarchists and the Domestic Enemy: the common enemy of civilized society, and the barbarians who would, if they could, become the destroyers of our race.” [emphasis in the original] [lxxxv]

Slave Population in 1860

American abolitionists developed contacts with Haiti, and slaves looked to the black republic for inspiration. In the mid-19th century, slaves in Louisiana were heard singing revolutionary songs first heard during the fall of Saint-Domingue. Southern whites “were not amused by celebrations of Haitian independence, such as that staged in 1859 by free negro masons in St. Louis, Missouri — a slave state.”[lxxxvi]

Still, the history of attempted slave revolts is mostly a story of suicidal rebellions. Despite their political sophistication, uprisings usually culminated in nihilistic violence preceding inevitable failure. However, from another perspective, every servile insurrection succeeded by striking terror in the hearts of whites, who never forgot Saint-Domingue.

The American experiment in multiracial egalitarianism was doomed from the start. Even Thomas Jefferson, whose Declaration of Independence arguably inspired slaves, was right when he wrote that the “two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government.”

* * *

[i] Aptheker, Herbert. American Negro Slave Revolts (International Publishers, 1993): 155-61.

[ii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 163.

[iii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 374.

[iv] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 141.

[v] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 143.

[vi] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 144, 147, 178, 189-90, 217-18, 281-82, 331, 353-54.

[vii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 145.

[viii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 143.

[ix] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 192.

[x] Genovese, Eugene D. From Rebellion to Revolution: Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the Modern World (LSU Press, 1992): 51.

[xi] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 72; Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 81-82, 91, 93.

[xii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 276-77.

[xiii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 68-69; Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 165, 171, 178-79, 191, 197, 206, 208, 217, 251, 258-59, 262, 266-67, 273, 277, 279, 280, 285, 288-90, 329, 335-36, 343, 345-46, 351-52.

[xiv] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 163-64, 166-67, 169, 172-73, 175-76, 180-84, 197-201, 204, 210-11, 215-17, 231, 240-46, 248, 254, 257, 262-63, 266, 277-78, 283-84, 286-88, 290-91, 307, 311, 331-32, 336-37, 339-43, 346-48, 351, 353, 356; Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 129; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 451; Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 128-29.

[xv] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 36-37.

[xvi] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 35, 40-41, 43, 197.

[xvii] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 45.

[xviii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 41-42.

[xix] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 24, 26-27.

[xx] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 19.

[xxi] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 22.

[xxii] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 29-30.

[xxiii] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 51.

[xxiv] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 219-26.

[xxv] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 63.

[xxvi] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 72.

[xxvii] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 67.

[xxviii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 43; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 451; Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 249-51; Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 67-68.

[xxix] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 8; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 452.

[xxx] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 104.

[xxxi] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 268-73.

[xxxii] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 106, 109.

[xxxiii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 268-73.

[xxxiv] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 110.

[xxxv] Gray, Thomas R. The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, Virginia (Baltimore: Lucas & Deaver, 1831).

[xxxvi] Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 452.

[xxxvii] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 117.

[xxxviii] Gray. The Confessions of Nat Turner.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Ibid.; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 452; Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 118-19.

[xlii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 299, 306-07.

[xliii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 334-35.

[xliv] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 14, 135, 137, 139-40, 144, 232-33.

[xlv] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 114.

[xlvi] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 14-15.

[xlvii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 185; Walters, Kerry. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies: A Reference Guide (ABC-CLIO, 2015): 21.

[xlviii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 293.

[xlix] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 15-16.

[l] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 16-17.

[li] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 17.

[lii] Egerton, Douglas R. “Slave Resistance” in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas. Paquette, Robert L., & Smith, Mark M., Eds. (Oxford University Press, 2016): 447.

[liii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 8.

[liv] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 26; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 449.

[lv] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 42; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 448.

[lvi] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 22, 86.

[lvii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 105.

[lviii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 45.

[lix] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 204.

[lx] Ibid.

[lxi] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 45; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 448.

[lxii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 27.

[lxiii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 202; Walters, Kerry. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 147.

[lxiv] Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 461.

[lxv] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 359-67; Egerton, in The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, 460.

[lxvi] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 357-58.

[lxvii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 79, 81.

[lxviii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 83.

[lxix] Walters, Kerry. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 242.

[lxx] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 303; Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 12.

[lxxi] Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 121.

[lxxii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 305.

[lxxiii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 105.

[lxxiv] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 109.

[lxxv] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 94, 111, 232-34, 255-56, 279-80, 325-29, 333-34, 338, 344-46, 351, 354-57; Walters. American Slave Revolts and Conspiracies, 152.

[lxxvi] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 343-44.

[lxxvii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 347.

[lxxviii] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 265-66.

[lxxix] Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts, 372.

[lxxx] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 126.

[lxxxi] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 127.

[lxxxii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 129-30.

[lxxxiii] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 45.

[lxxxiv] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 94-95.

[lxxxv] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 96.

[lxxxvi] Genovese. From Rebellion to Revolution, 96-97.