‘Joker’ — The Face of America

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, October 17, 2019

Todd Phillips’ Joker has drawn controversy from the Left and Right, with some critics hailing it as a “masterpiece” and others not knowing “if it should be banned or it should be given every award.” Reviewers have tended to treat Joker as a character study of a man’s descent into madness. But by the film’s end, we’re left knowing little for certain about clown-for-hire Arthur Fleck. We do learn much, though, about the society he lives in.

Fleck’s strange qualities make him a touchstone for Gotham City, revealing the city’s festering tensions and atomized citizenry. Likewise, the Joker movie itself is a touchstone for our society, laying bare viewers’ prejudices, rank media bias, and progressives’ surrender to anti-white politics.

Here’s a plot summary you can skip if you’ve seen the movie (spoilers ahead):

Arthur Fleck, a mentally ill man suffering from the pseudobulbar effect (laughing or crying at inappropriate times), works for a clown-booking company in 1981 Gotham City. In the opening scene, non-white teenagers steal one of his props and brutally beat him. Fleck lives with his mother and likes to watch a late-night talk show — “The Murray Franklin Show” — with her, imagining Franklin as a father figure. He has a friendly encounter with a black single mother, Sophie, who lives in his apartment building. He invites her to his stand-up comedy act, which begins disastrously but seemingly ends well.

Fleck can no longer see his social worker or get psychiatric medication because of budget cuts. He loses his down job when his gun falls out of his pocket during a performance. Three drunk white businessmen attack him while he is his clown costume on the subway. Fleck uses the gun to shoot them, and then crosses the line from self-defense to murder when he stalks the last fleeing victim and guns him down. He returns to the apartment, knocks on Sophie’s door, and passionately kisses her.

The shootings are spun by the media as an attack on the rich, and many ordinary people approve of the killings. Thomas Wayne, a mayoral candidate and father of Bruce Wayne (who becomes “Batman” in adulthood), condemns them. He calls the underclass “clowns,” thus turning the clown into a symbol of rebellion.

Fleck loses his grip on reality when he opens a letter his mother wrote and learns that he may be Thomas Wayne’s son. He goes to Wayne Manor but is chased away by the butler. He goes home to find his mother has had a stroke, seemingly traumatized by police investigating the subway murders. He accompanies her at the hospital, where he sees a clip of his disastrous stand-up performance played on “The Murray Franklin Show” to mock him. He is shattered. He later infiltrates an event and accuses Thomas Wayne of impregnating his mother. Wayne says Fleck’s mother was crazy and punches him in the face.

To find out the truth about his origins, Fleck goes to the mental institution where his mother was interned and finds her records. They say he was adopted, that his mother is crazy, and that she let an old boyfriend beat him when he was a child. Fleck is furious and smothers his still-ailing mother with a pillow. He then shows up in Sophie’s apartment, but she is terrified of him and tells him to leave. His relationship with her was a fantasy.

Fleck gets a call from the Murray Franklin program, asking him to come on as a guest because of the extraordinary reaction to his performance. He agrees, and it is implied that he will commit suicide on live television. Two former co-workers, one a midget and the other the man who gave Fleck the gun, come to visit him, ostensibly to commiserate over his mother’s death. Fleck, who has a grudge against the one who gave him the gun, brutally kills him, but lets the midget go.

Emotionally liberated, Fleck leaves in an outrageous suit and wearing clown makeup. Two detectives chase him to the subway, but the cars are filled with protesters wearing clown masks, and Fleck escapes.

(Credit: DC COMICS/DC ENTERTAINMENT / Album)

At the studio, Fleck asks Murray to introduce him as “Joker.” On air, he blurts out that he committed the subway murders and then gives a speech about what is wrong with society. Then he shoots Murray in the head on live television. The city is engulfed in riots. Thomas Wayne and his wife are among the victims, and we see another version of the now iconic Batman origin scene.

Fleck is arrested but rejoices in what he’s unleashed. The cop car he is in has an accident. Protesters look inside, see Fleck, and lay him on top of the car. Christlike, he rises from seeming death and grins bloodily while the crowd cheers. The Joker is born.

The movie doesn’t end there. Instead, we see Fleck in his mother’s mental institution laughing to himself while a psychiatrist asks him what’s funny. “You wouldn’t get it,” he replies. As Frank Sinatra’s “That’s Life” plays in the background, he runs out of the room with bloody footprints, implying that he killed the therapist.

Fleck is an unreliable narrator. The last scene is not the first to raise the question of whether any of the events in the movie happened, or if they are all a maniac’s fantasy. For a “realistic” movie based on comic book characters, the plot grows more unbelievable with every twist:

- A co-worker simply hands Fleck a gun. Do liberals believe this happens all the time?

- A national talk show host devotes a segment to mocking an unknown aspiring comic. In the pre-YouTube age, where did he even find the video?

- A mentally ill loner who can’t hold a job somehow infiltrates a closed event guarded by police, later dodges pursuing officers, and finally brings a gun onto a television set where he kills his victim like an experienced hitman.

The extremely unattractive Fleck occasionally acts like a charismatic movie star, coolly smoking while plotting his next move. One suspects these little moments happened only in his head, but it’s impossible to know. The “relationship” with Sophie was clearly imaginary from the beginning.

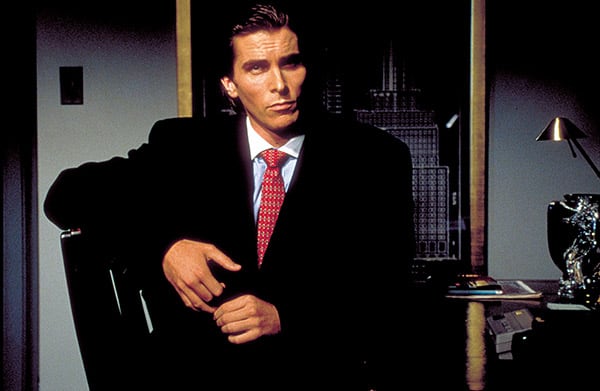

Hunter Wallace at Occidental Dissent independently reached the same connection I did, that Joker, Fight Club, and American Psycho can be seen as a trilogy, portraying the consequences of consumerism and deracination on the working poor, the middle class, and the rich, respectively. All have unreliable narrators. All have white protagonists. All appealed to the Right more than the Left, despite the filmmakers’ intentions.

Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman in “American Psycho.” (Credit Image: © Courtesy of Muse Productions/Entertainment Pictures/ZUMAPRESS.com)

The film version of American Psycho was directed by a woman who wanted to critique misogyny and corporate capitalism, but inadvertently made it look attractive by leaving out the protagonist’s most revolting crimes and pathetic qualities. The film version of Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club didn’t discredit masculinity, but (perhaps inadvertently) encouraged tribalism and masculinity. Joker could be a critique of the collapse of the welfare state (Michael Moore and The Guardian make this claim), but instead, many reviewers are angry because a white man is the victim:

- “’Joker’ Is a Terrifyingly Realistic Window Into White Terrorism,” VICE

- “The Real Threat of ‘Joker’ Is Hiding in Plain Sight,” claims the New York Times, which calls it a “depiction of what happens when white supremacy is left unchecked.”

- “‘Joker’ – a political parable for our times,” CNN: “[A]n insidious validation of the white-male resentment that helped bring President Donald Trump to power.”

CNN’s take is amusing because the film sets up Thomas Wayne as the villain. Instead of the gentle, altruistic doctor from Batman Begins, Joker’s Thomas Wayne is an evil caricature of President Trump. (Saturday Night Live’s Trump impersonator Alec Baldwin was originally cast for the role.) It’s not even clear that Fleck’s mother is lying about her affair with Thomas Wayne; a photo with an affectionate note from “T.W.” suggests he put her in an asylum and forged the adoption papers. Actor Brett Cullen said he portrayed Thomas Wayne as though the affair was real. This also raises the possibility that Bruce Wayne, once he’s “Batman,” will be a guardian of the rich against the unruly poor who killed his parents.

The talk show host Murray Franklin is thuggish and reactionary. He’s far from the left-wing late-night hosts tediously bashing President Trump every evening. Still, journalists and entertainers (increasingly the same thing) couldn’t have been comfortable about a scene in which the antihero guns down a media figure on live TV and the masses rejoice.

The subway shootings are an almost direct allusion to the famous 1984 Bernhard Goetz case, when a white man shot four blacks who threatened him. In this film, three Wall Street “bros” (the quasi-slur reviewers use to describe the white men) are the attackers. The multiracial, anti-capitalist movement that arises (complete with signs proclaiming “resist” and denouncing the “fascist” Wayne) is a leftist’s dream, but writer/director Todd Phillips is getting no credit for any of this. No wonder he’s so frustrated with “woke culture.”

(Credit: DC COMICS/DC ENTERTAINMENT / Album)

Fleck’s imagined love interest is black. He shares what appears to be a genuine moment of commiseration with her, in what is one of only two real human connections he gets (the other is with the midget whom he lets escape from his apartment because the midget was kind to him). Sophia is an entirely sympathetic character, but this, too, is racist according to some reviewers because black women are not central to Fleck’s story. Obviously, this movie is about Fleck and his inner life. They’ve already made Precious.

Fleck is pitiable. Mentally ill, incel, poor, a victim of abuse, but above all innocent at the beginning of the film. This is the kind of person progressives used to champion, but because he is white, countless articles and tweets suggest that even trying to understand the “root causes” of his rage is complicity with terrorism.

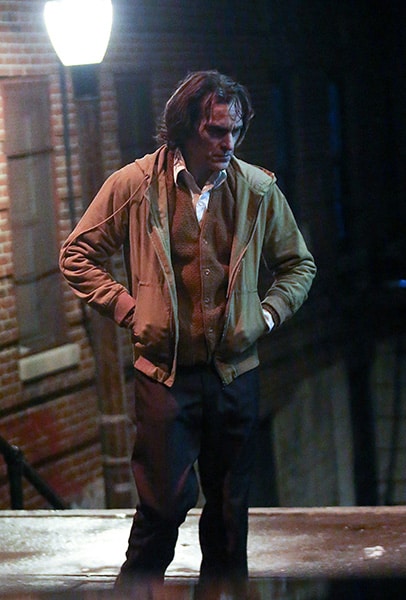

(Credit Image: © Philip Vaughan/Ace Pictures via ZUMA Press)

The few progressives who defend the movie miss the point. Fleck does lose his medication and his social worker. However, therapy and drugs aren’t working. After his subway murders, when he tells his social worker that for the first time he feels like people are paying attention to him, he notices that she is not paying attention — that she asks the same questions every appointment. She feigns interest in him only when her office’s budget is cut: “They don’t give a shit about people like you, Arthur. And they don’t give a shit about people like me, either.”

Whether she had an affair with Thomas Wayne or not, the real villain of the film is Fleck’s (possibly adoptive) mother. She may have trapped her son in the prison of her own madness. At the least, she allowed him to be abused, which probably led to his handicap. If we want to talk about “root causes” of Fleck’s tragic life, the collapse of the family and the rise of single motherhood are at the top. Even Sophie seems crushed by the burdens of single motherhood – hardly an empowered woman. The two most prominent victims (Murray Franklin directly and Thomas Wayne indirectly) are both absent father figures.

Before Fleck shoots Murray Franklin, he decries society’s lack of civility. This may seem contradictory, but it’s not. Almost every time Fleck bursts into “inappropriate” laughter, it’s when he’s met with cold contempt rather than basic politeness. The very first thing he does in the film is try to reclaim his prop from thugs who stole it, but he gets a beating for his efforts. His employer then docks his pay for losing the prop.

When Fleck gets a single moment of human contact, with Sophie, it affects him so much that he fantasizes an entire relationship. After the especially brutal murder of a former co-worker, Fleck lets the midget co-worker go because he was “the only one who was ever nice to me.”

Events in Joker can be interpreted in different ways. One of the film’s attractions is how it challenges the way Americans interpret events in their own reality. When Fleck kills the three Wall Street men, it’s because they attacked him. The first two killings are justified self-defense. Yet hostile media and the Gotham underclass immediately give the killings political significance as an attack against the rich. Before he shoots Murray Franklin, Fleck explicitly denies any political purpose, but the shootings launch a pogrom against the upper class.

Fleck becomes “free” through violence, by murdering a symbolic father (Murray Franklin), the woman who raised him, and by indirectly killing the man who may have been his real father. His killings were personal, but the Joker becomes a hero to the crowd because he is an avatar of the revolutionary chaos and destruction they long to see.

Much of the commentary about this movie is about the supposed threat of mass shootings. It almost seemed like journalists were trying to encourage one. I can recall no such warnings about Get Out, Django Unchained, Machete, The Birth of a Nation, or the other kill-whitey films that have multiplied over the last few years. Thus far, the media have been disappointed, especially since a recent string of murders against homeless people looks like it was committed by a mentally ill non-white. In effect, the media’s coverage of Joker proves the film’s point: People are willing to read their own beliefs and motivations into the actions of others, even when others are acting out of personal grievance or sheer lunacy.

During the film, I kept thinking of Lana Lokteff’s speech about “Clown World” at the most recent American Renaissance conference. She explained the importance of the “fool” archetype at times of inverted values. During this period of decline and social chaos, the “fool” can speak forbidden truths.

Fleck is not a hero. He is a particularly violent form of the fool. Such characters are inevitable in a degenerating society. He is a problem that can’t be solved by taxing the rich, throwing more money at programs, or talking about “white privilege.”

(Credit: DC COMICS/DC ENTERTAINMENT / Album)

What’s needed is something more fundamental, a return to real communities that give people a real identity. Without that, people of any economic class or race feel they have no stake in anything. Fleck says, “I didn’t even know if I exist, but I do.” He says this only after he becomes a murderer. It’s not surprising that people lash out; it’s surprising more don’t.

The violence, the mass shootings, and the casual sociopathy of modern America are not simplistically political in the way many journalists want them to be. America’s soul has been ripped out, and these acts are existential rage, not political terrorism. Alienation is not a matter of Left and Right. It’s something far deeper, and the grim, hostile world of the Joker is just believable enough to appear as a brilliant projection of our increasingly diverse, rootless society.

It also shows how the media sensationalize violence and bend it to their own political purposes. The film in effect broke the fourth wall – addressed the audience – by vividly portraying what our own media so often do.

What is the solution? It remains for us to create a new way of living or perhaps to return to one that was better. This includes building a home where our own people will feel safe, appreciated, and free. Otherwise, the madness we see on screen will continue to bleed over into reality until we descend into chaos or are conquered from without. The laws of history are harsh. In the end, Fleck is right: “You get what you f***ing deserve.” He’s speaking not only to a contemptible talk show host. He’s speaking to all of us.