White Renegade of the Year — 2018

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, January 1, 2019

“To see and not to speak would be the great betrayal,” said Enoch Powell. Worse is to see, to know, to speak, and then act destructively anyway. Angela Merkel, White Renegade of the Year 2015, did this when she welcomed a massive migrant flow into Europe years after declaring multiculturalism was a failure. Yet this year’s renegade has less excuse. He clearly warned of the consequences of mass immigration, but still pushes catastrophic policies on his people — even in the face of failure and furious opposition. This year’s White Renegade of the Year is the president of the French Republic, Emmanuel Macron.

President Macron won election in 2017 thanks to a quirk of the electoral system. In a runoff against the nationalist Marine Le Pen and her National Front, he won a commanding 66 percent of the vote, compared to about 34 percent for Mrs. Le-Pen. Many voters were motivated not by Mr. Macron’s positive vision, but by a desire to stop the National Front. A relatively large number of voters abstained in the second round and almost ten percent turned in blank ballots in protest. Mr. Macron acknowledged many had not voted for him out of agreement, but “simply to defend the Republic” — thus implicitly banishing Marine Le Pen and her supporters from republican legitimacy.

Still, Mr. Macron surprised some critics in his early months. He seemed different from the typical liberal politician. Early on, he became friends with President Donald Trump, who appeared far more comfortable with President Macron than with Chancellor Merkel. President Macron mused about the vacuum in French politics created by the absence of monarchy, and the need for strong personal leadership. Though this led to some criticism, President Macron also tried to restore dignity both to his office and politics generally, notably scolding a youth for addressing him by an informal nickname.

More importantly, President Macron spoke seriously about the problems of mass immigration and overpopulation in the Third World. He shocked journalists by dismissing a suggestion that a “Marshall Plan for Africa” would do any good, and said one of the “essential challenges” was Africa’s high birthrate. Accusations of colonialism, imperialism, and of course racism came from all quarters, including the supposed conservatives at National Review. President Macron defended the distinction between economic migrants and asylum seekers, and even cracked down on immigration in ways that some journalists called “brutal.”

President Macron shepherded a bill through the legislature that expedited deportation of failed asylum seekers. It was condemned by some nationalists as not strong enough, but it was still a defense of French sovereignty. Finally, President Macron spoke about the need for Europe to develop a coordinated approach to refugees, saying in an interview that had such an approach existed years ago, “we would never have had to deal with that first route from the Balkans that allowed millions of refugees to come to Europe.”

President Macron thus identified the policy that could save the European Union. President Macron is one of the EU’s greatest defenders and even played the European anthem, “Ode to Joy,” after his election victory. Many journalists have called President Macron a potential “savior of Europe” from nationalism and the “far-right.” Yet the best way for President Macron to do this would be to organize a continent-wide approach to stopping immigration. Steve Sailer has repeatedly argued that the European Union would become more popular if it halted immigration. It would also mean the European Union would be “pro-European” instead of “pro-Syrian, pro-Afghan, and pro-Eritrean.”

Emmanuel Macron arrives to the Europa Building for the European Council Summit in Brussels on December 13, 2018. (Credit Image: © Dominika Zarzycka/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

One continuing discussion among white advocates is whether an imperial Western empire or a looser union of separate, independent ethnic homelands is better. The current European Union is the worst of both. The EU’s bureaucrats strip sovereignty from European nation-states, repress patriots, and govern like petty tyrants. While embracing all the worst features of empire, they act in ways that are utterly alien from the peoples they govern. It’s like living under a council of diversity coordinators that has the power of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Most white advocates therefore support nationalism and limiting the European Union’s power, if not dismantling it altogether. Yet it did not have to be this way. The most forceful argument for a centralized European Union organized along racial lines came from Sir Oswald Mosley’s postwar concept of “Europe a Nation.” Even some supporters of European populism recognize the advantages of the European Union, including the currency union, free travel, and the possibility of a common defense. Solid majorities in every European nation (except Italy) believe their countries have benefited from membership. Marine Le Pen’s call to withdraw from the monetary union was supported by only a minority of French voters and probably hurt her chances in the election. Populism is a growing force and nationalism is far from dead, but Europeans generally do not want to leave the EU, whatever true nationalists think about it.

The union’s current approach to immigration is deeply cynical, with nations trying to pawn off unwanted migrants on each other while they talk piously about collective responsibilities. Instead of forming a community of common interests, the European Union’s courts are trying to force states like Hungary or Slovakia to swallow hundreds of thousands of unwanted aliens.

Of course, these migrants wouldn’t be in Europe were it not for Angela Merkel’s unilateral decision to put out the welcome mat for Third World refugees or the decision by several Western governments to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi. As it now operates, the European Union is a civilizational suicide pact. Yet most Europeans, even Eastern Europeans, grumble and put up with it because they don’t want to lose the benefits of membership.

Thus, there was a real opening for Emmanuel Macron if he was serious about reforming the Union. With common sense border-control and a collective approach to stopping migration, President Macron could have turned the EU into a civilizational defense pact. Such an approach would have meant President Macron could have credibly pushed for greater European centralization and even a European army — perhaps fulfilling his quasi-imperial pretensions. It would also have co-opted much of the support for populist, anti-immigrant political parties.

President Macron did not do this. Instead, he appointed himself the successor to Angela Merkel. The turning point seems to have been the Italian elections in March, in which anti-immigration populists triumphed and eventually formed an anti-establishment government. Initially, President Macron acknowledged that Italian frustration over immigration was justified and partly explained the results. Of course, President Macron bears some responsibility for the results himself because he angered Italian authorities in 2017 by refusing to take migrants off their hands. Unfortunately, rather than being chastened by the election, President Macron hardened his opposition against Europe’s populists, particularly the governments of Italy and Hungary.

In so doing, President Macron may have been following the advice of elite journalists who called him a champion of “European values,” if not European people. After the Italian elections, the Washington Post’s editorial board urged him — ludicrously — to ”rescue democracy.” In April, in a speech to the US Congress, President Macron attacked “isolationism, withdrawal, and nationalism.”

In June, Mr. Macron picked a fight with the Italian government: After Italy prevented an NGO’s ship from landing migrants in the country, President Macron raged against “cynicism and irresponsibility,” and a spokesman for his party said the policy “makes me vomit.” Italy’s prime minister accurately retorted that France had not met its own immigration obligations. Mr. Macron backed down, claiming he didn’t mean to offend the Italians. European leaders, including Mr. Macron and Prime Minister Conte of Italy then signed an immigration agreement, though the exact terms were vague.

Despite this brief peace, in June, President Macron called himself the “main opponent” of nationalist leaders Prime Minister Viktor Orban of Hungary and Interior Minister Matteo Salvini of Italy — the two most prominent Europeans who speak for the West. “It is clear that today a strong opposition is building up between nationalists and progressives and I will yield nothing to nationalists and those who advocate hate speech,” he said in August. The next month, he threatened to withhold funding from countries that would not accept migrants. This was astonishing since France is regularly criticized for refusing to accept refugees and for dumping them on Italy. Indeed, that same month, Italian witnesses claim French police drove black men across the border in a van and released them into the woods.

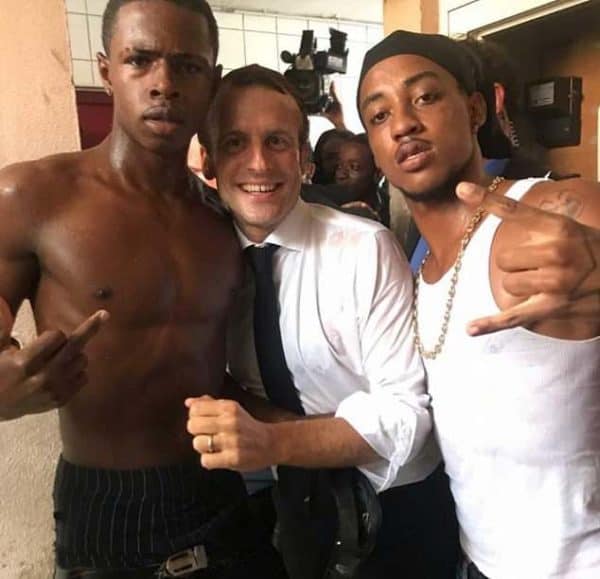

In September, President Macron’s quest to restore gravitas to his office suffered a blow when he was photographed a with two young black men in Saint-Martin. One of the men is shirtless and giving the camera the middle finger. This makes his lecture to a young Frenchmen about respect seem ridiculous. President Macron refused to apologize, even taking the opportunity to attack Marine Le Pen in self-righteous terms. “I love all of the republic’s children, whatever their past troubles,” he said, referring to the young man’s run-ins with the authorities that the media brought to light. As if on cue, one of the men was reportedly arrested for drug possession and resisting arrest about a year after the photo op.

President Macron is now in open battle with Prime Minister Orban and Interior Minister Salvini. “We’ve accepted this political divide and are organizing around it,” said one French official, adding that the government was in a “logic of combat.” In preparation for the EU elections in May, President Macron met Mark Zuckerberg to set up the first-ever partnership between Facebook and a national government to police “hate speech.” President Macron also insulted President Trump at a Remembrance Day ceremony. “Patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism; nationalism is a betrayal of patriotism,” he said in what was clearly an open attack. In December, President Macron ended the year by signing the UN Migration Pact, which he called “laudable and desirable.” This action reportedly drew accusations of “treason” from some generals.

Of course, whatever aspirations President Macron may have to being a European or global leader, his biggest problems now are domestic. The “yellow vests” protests against his tax hikes and neoliberal economic policies aren’t stopping, and may bolster his opponents in the upcoming EU elections. While the protesters don’t share a common political program, polls suggest that many are nationalists, and almost all the members of the National Rally (the rebranded National Front) support the movement. Originally, the French government even blamed Marine Le Pen for starting the demonstrations. Some videos show protesters ripping down EU flags.

French yellow vest protesters tear down EU flag in move against globalism. pic.twitter.com/IxY1z0Ttd1

— Voice of Europe 🎆🌠 (@V_of_Europe) December 30, 2018

The French police have responded with notable brutality. Amnesty International claims it “has documented numerous instances of excessive use of force by police.” Le Monde, arguably the most prestigious French newspaper, even likened Mr. Macron to Adolf Hitler (though it later apologized). Yet the mainstream media in the English-speaking world still largely supports President Macron. “Macron’s crisis in France is a danger to all of Europe,” writes Natalie Nougayrede of The Guardian in a typical piece.

The obvious response is, “Which Europe?” The Hungarian and Italian governments are President Macron’s primary foes, yet both are stronger than his administration today. Though Prime Minister Orban’s government is encountering widespread protests in response to economic reforms and the Fidesz party is dropping in the polls, it is still the dominant political party. In Italy, Interior Minister Salvini’s Lega party commands a strong lead over all other parties. Interior Minister Salvini is downplaying his prior opposition to the Euro and is instead creating a broader-based populist movement. If the May EU elections go well, he may even attempt to take control of the Italian government by pulling out of the coalition with the Five Star Movement.

Italy, BiDiMedia poll:

EU election

LEGA-ENF: 34% (+1)

M5S-EFDD: 25% (-1)

PD-S&D: 17%

FI-EPP: 7%

FdI-ECR: 4%

+E-ALDE: 4% (+1)

CC-*: 4% (+1)

A1-MDP-S&D: 1%

SVP/UP-EPP: 0%+/- with Nov 2018

Field work: 17-21 Dec 2018

Sample size: 1,018#EP2019➤ https://t.co/yZmKw0FzEV pic.twitter.com/PoFeMXWiPc

— Europe Elects (@EuropeElects) December 29, 2018

In contrast, a recent poll taken just before Christmas found President Macron is now supported by just 23 percent of voters. For comparison’s sake, even in the midst of a government shutdown and in the face of furious media, President Donald Trump’s approval rating is above 40 percent. According to some polls, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party is leading President Macron’s party, only five months before the 2019 EU elections. Adding to his political woes, President Macron is also ending the year with a scandal, as a former aide fired for beating a protester admitted he kept using his diplomatic passport.

Despite all of this, President Macron is unlikely to back down. Members of his party have argued that the best way to combat nationalism is to strengthen the European Union. Though the protests have shaken his government, President Macron is far from finished and still enjoys a parliamentary majority. More importantly, though nationalists are gaining strength in both Germany and France, so is the hard Left. There is no sign of a nationalist takeover in either country anytime soon.

Emmanuel Macron is a tragic figure because he could do so much good with even moderate reforms. He could save the European Union he loves so much and defeat the nationalists he so hates. What’s more, his extraordinary comments about Africa suggest he is more aware of the long-term problems facing the world than any other Western leader except Prime Minister Orban.

A Yellow Vest carries a placard reading “President Liar.” (Credit Image: © Alain Pitton/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

Yet for all the media excitement about President Macron’s youthful leadership for the EU, his ideas are nothing new. His France is an administrative entity. His European Union is an anti-European bureaucracy dispossessing the indigenous nations, cultures, and peoples. His “democracy,” in league with Mr. Zuckerberg, allows only certain views to be expressed and it attacks demonstrators just as eagerly as “authoritarian” Hungary or Russia. Like Angela Merkel, President Macron is bringing on “preventable evils,” and unlike her, there’s reason to believe he knows it won’t work. He is acting as if he would rather preside over a continent of ashes than the Republic of the French. President Emmanuel Macron is the White Renegade of the Year — and unfortunately, he is just getting started.