The Education of a Race Realist

Rafe Aegirson, American Renaissance, November 10, 2017

The great classicist and philosopher Clive Staples Lewis held that each generation, whether it knows it or not, is prone to some special eccentricity. If one day, centuries hence, some remnant of our people is left to reflect upon its racial past, it will surely look back upon this present era as one of the oddest in its history.

I was born in the post-war era and grew up at a time when a culturally white America still bore some resemblance to a nation. Ask someone from that era what they remember of it, and they may tell you about amusement parks, malt shops, and weekly televised ballgames with Diz and Pee Wee; about eerie TV science fiction and network family dramas that brought a household together in the evening. Along with this went civilized schools and a workplace that was not yet plagued by the destructive policies that contaminate it today. It was a simpler and more honest time.

My family lived in the most integrated part of town, so my awakening moments to race came early. Some were benign and even amusing. I still remember making Halloween masks in first grade — this was the fall of ’57 — when my black friend Kenny cut into his brown bag from the open end and made a mouth by cutting a circle rather than folding the surface and making a neat wedge-cut as seemed natural to the rest of us. In time, differences would be less benign.

In fact, the pressure was already on to decry “prejudice” and enlighten us about the “human race.” Beneath the skin, it was said, we were all of one substance. I remember a picture in a comic book of three runners (black, white, and yellow) tied at the finish line. “Scientific tests” had established this result.

I couldn’t help but wonder, even then, how tests could have proven something that flew in the face of common experience. We might not have had a theory about race, but we knew what to expect: Vivid differences in every activity. The “colored kids,” on average, were boisterous and extroverted, but they were generally well-liked, despite their sporadic aggression. They were “good at sports” and remarkably quick at 50 or 100 yards. Also, practically every one needed remedial texts and extra help with even the simplest classroom tasks.

Black militancy came in the next few years, and meant bloody noses for a lot of white kids. At 13, I was the target of a murder attempt — it’s odd that it did not occur to me until years later to describe it in that way — by one dark youth who twice, without provocation, pitched rocks nearly the size of a baseball at my head. If his aim had been better, you would not be reading these words.

* * *

By my mid-teens the AM airwaves were thick with Judy Collins, the Young Rascals, and refrains about universal love. Bob Dylan was whining about how many roads “a man” had to walk down before we might “call him a man.” If white guilt was not yet in full bloom, its seeds were being sown.

Bob Dylan performs on stage with his harmonica and guitar at Madison Square Garden. (Credit Image: © Gijsbert Hanekroot/Sunshine/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Through high school and college, during the height of the Vietnam War and the “Civil Rights” movement, I maintained an odd kind of liberalism, even as I resisted the idea that black underachievement was caused only by injustice. Around my senior year in high school, I noticed a tabloid publication on the newsstand, with an article about Arthur Jensen, a scholar who said that blacks and whites might differ in average intelligence. I felt vindicated. What Jensen said fit well with what I had been seeing for some time.

There were many other formative incidents in those years. When I was a senior, the psychology teacher asked me to help a couple of lagging students write an outline for oral presentations. One of them was Stan, a star black athlete whom I had known slightly for about 10 years. I did not see him as a hero the way most of the school did, but I put aside my misgivings and explained what was needed.

I paused after a couple of minutes and looked at him, getting back only a puzzled smile. I tried several more times, until I was putting the problem in the simplest terms that logic and language would allow, and each time got that befuddled look.

It was not Stan’s fault that he was unable to grasp what virtually any white student half his age would have understood. In time, I began to wonder why schools continued to teach subjects like English literature and math to people who did not care about them.

It was not just Kenny, or Stan, or some crazed black throwing rocks. There was a fundamental delusion being foisted on whites about the “equality” of “people of color.”

Over the coming decades came an incessant egalitarian push from the media. Traditional family programming gave way to television comedies trying to expose “prejudice.” Typically, there was a crotchety white man who served as the foil for prattling blacks and agile liberals who one-upped him at every turn.

By now I was revolted by popular media. Why were white characters always incompetent? Why were they the ones who always started racial conflict? I wanted to see a portrayal of the other 90 percent of what went on in the world.

* * *

In time I became an educator and started teaching young people who had been steeped from infancy in this stuff. The absurdity of the classroom played out all over again, as encounters with non-whites reinforced the message of my childhood.

Year in and year out we heard about a tragic “gap” in school achievement, and what might be done to close it. We also heard that marginalized victims are held to a higher standard, both in school and at work. Of course, equal treatment would widen the gap. Give the average black student what he supposedly wants — a fair shake — and he will very likely be gone from the campus in six months. Set a reasonable standard, and he is unable to meet it; extend help, and he is uninterested; fail him, at last, and he is a victim of racism.

The demand for equal opportunity has become a demand for equal results and has led to an erosion of standards. Likewise has come an erosion of personal freedom. For fear of professional ruin, no one in the mainstream today dares to say — as I recall columnist James Kilpatrick saying about Jensen — that the time has come to let go of the sacred dogma of equal aptitude across the races.

Much of traditional discussion about race has emphasized IQ, but IQ is just one aspect of racial difference. There is also a fundamentally different orientation to the world. I believe some groups are, on average, more impulsive and less patient. I think they are also less able to think about reality as it is, rather than how it appears to them. Some groups are more subjective than others.

For example, many blacks ignore the repeated instructions of a police officer. They never stop to think that an officer potentially risks his life when he approaches a suspect of any race on the street.

In “reality” show courtrooms, most blacks are unable to let their opponent have his say, and they pay little attention to the judge. Blacks will often “guarantee” something to gain an advantage or promote a transaction; they feel that their sheer certainty — often unfounded — should be enough to decide the matter. I wonder how many black activists have ever spent six seconds putting themselves in the place of the people they are berating.

Another index of black temperament is strong avoidance of libraries, which are quiet havens set aside for studying. When I heard about an invasion of the Dartmouth College library by Black Lives Matter activists, I wondered whether this might have been the first time some of those black students had set foot in the place.

* * *

For a long time I wondered how things so obvious to me were not obvious to most of the whites I knew. I imagined that race liberals were foolish but essentially innocent in their outlook. I supposed that white liberals and intellectuals were different from the rest of us because they were street-ignorant. Accordingly, I thought that the “we are all alike” message was the best that scholarship had to offer.

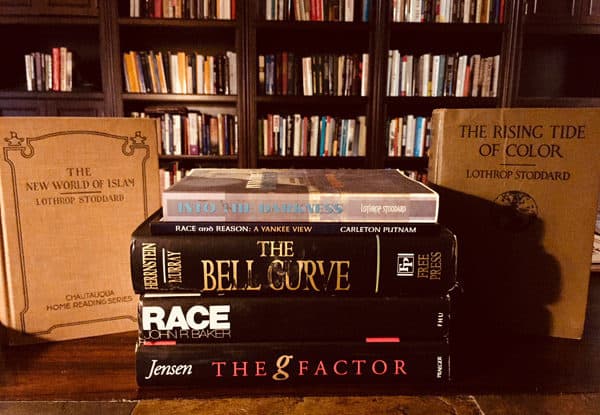

This changed about 30 years ago when I saw a television program on white “extremists” near my home town, which mentioned a “white supremacist bookstore” southwest of the city. I managed to track it down and discovered a whole family of unfamiliar authors. I left with an armload of treasures.

I still imagine that a great deal of race liberalism is naiveté. There is no substitute for “face to face” experience with real life. But those books changed my outlook on the race problem, because until then, I had imagined that liberalism was aligned (even if accidentally) with good scholarship. I expected these materials would be less acute than mainstream scholarship.

Imagine my surprise when I read Carleton Putnam’s Race and Reason and found that an American businessman and airline executive had written the most lucid discussion of race I had ever seen in my life. Eventually I discovered John Baker, Lothrop Stoddard, Wilmot Robertson, Carlton Coon, Revilo Oliver, and others. Soon I learned of a new monthly publication called American Renaissance.

But even more important than knowledge, I gained soundness of mind. Many whites lead a schizoid existence. The sources that they trust — the nightly news, school, magazines, movies, even the pulpit — tell them one thing. They ask themselves, “Am I a racist?” They imagine vaguely that God, or science, or ethics, cannot possibly be on the side of racial “inequality.”

These writers showed me that my instincts about race were supported by the best scholarship. Yet this discovery got me wondering: Why weren’t these books in my high school library, or anywhere else that would have been readily available?

Obviously, our society was suppressing the truth about race. It still is. Now that the internet has made it much easier to find heretical views, heretics are “deplatformed” by the giant tech companies that control access to information.

But they can’t run this shell game any longer. Even if AmRen were shut down, other sites would take its place. We now have all the knowledge we need for sane racial policies. What we need is the nerve to put the into practice.

If you have a story about how you became racially aware, we’d like to hear it. If it is well written and compelling, we will publish it. Use a pen name, stay under 1,200 words, and send it to us here.