Interview with a Pioneer

AR Staff, American Renaissance, February 19, 2016

Richard Lynn is one of the great, pioneering psychologists of our time. Like other giants in his field, such as Cyril Burt, Hans Eysenck, Arthur Jensen, and Philippe Rushton, he has pursued truth rather than popularity. This has led to findings that today’s orthodoxy denies: that there is a substantial genetic contribution to individual and group differences in intelligence and other traits. No other psychologist has studied the nature and implications of these differences more extensively than Richard Lynn.

Prof. Lynn is the author of 15 books, of which American Renaissance has reviewed Dysgenics, IQ and Global Inequality, The Chosen People, Race Differences in Intelligence, The Science of Human Diversity, and Eugenics.

In this extensive interview, Prof. Lynn looks back over an astonishingly productive career, and warns of the dangers in store for the West if it continues to deny individual and group differences.

I understand your father was a plant breeder. Did that give you an early appreciation for the importance of genetics?

RL: Yes, he was a plant breeder and also a plant geneticist who published a number of papers on the genetics of cotton in scientific journals, and he was also a eugenicist. He was one of the signatories of The Geneticists’ Manifesto drawn up by Hermann Muller in 1939, which posed the question “How could the world’s population be improved genetically?” My father’s interests did give me an early appreciation of the importance of genetics, although I think I would have adopted this position anyway since the evidence is irrefutable for a strong genetic determination of intelligence and educational attainment and a moderate genetic determination of personality. More importantly, my father served as a role model for scientific achievement and has given me the confidence to advance theories that have sometimes been controversial.

Your degrees are in psychology. What prompted your interest in this area?

RL: When I was in school I was bored by science. It all seemed so cut and dried. All you had to do was learn it. I found a lot of it very tedious, especially the practicals. You could spend a sunny afternoon pouring sulfuric acid on potassium and discover you ended up with potassium sulfate. I was quite happy to learn that this was so. I have a touch of ADHD that make it difficult for me to pay attention to lessons I find boring, and this made science classes even more uncongenial. I liked history and literature, in which there were differences of opinion and we were encouraged to make up our own minds about what was right. I have found this early education valuable, as I have often taken a different view to the received opinion. So when I went up to Cambridge in 1949 I began reading history. I liked it, but I did not fancy making a career in it. So much history has been done already that all you can do is add a footnote of the kind written by one of my contemporaries: “Trade between Bristol and Bordeaux, 1485–1490.” Or you could write another account of, say, the First World War, suggesting slightly different interpretations of some events. I did not think I would find any of these prospects satisfying. So I opted for psychology, a new science with a lot of scope for making new discoveries.

In 1967, you moved to Ireland, and spent the rest of your professional career there. Why Ireland?

RL: My first job was at the University of Exeter (1956–67), which I have described as my wilderness years. My father had advised me that the trick for an academic career is to find your gold mine and then exploit it, but I found this was easier said than done and I had not managed it. However, I was beginning to explore what was to become my gold mine, which was the IQs of nations and their important contribution to economic development. In 1963, I read David McClelland’s book The Achieving Society, which presented a theory that the economic rise and fall of nations is determined by the rise and fall of a psychological trait he called achievement motivation. I was greatly taken by this theory although I later came to the view that it as all wrong. Still, it set me thinking about the psychology of the economic rise and fall of nations and led eventually to my theory that intelligence is the main factor. In 1966, I made contact with Ralph Harris and Arthur Seldon, the people who ran the Institute of Economic Affairs in London, a free-market think tank to which I was sympathetic, and where I developed my interest in the integration of psychology and economics. Then in 1967 a job came up at the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin, which I thought would be a good environment in which to develop these ideas further.

In the mid 1970s you began seriously studying racial differences in intelligence. Why were you interested in this subject?

RL: While I was in Dublin I had the idea that national differences in IQs could be an important determinant of economic development. I made two discoveries that encouraged me to develop this theory. The first was that Ireland was performing poorly, economically, and I dug out research showing it had a low national IQ of about 94 compared to 100 in Britain. The second discovery was about Japan. At this time everyone was impressed by the Japanese “economic miracle,” and in 1972, I hit on a way of measuring the Japanese IQ and, at around 107, I found it significantly higher than that of Europeans. These discoveries set me on the road to collecting more national IQs, and also regional IQs within countries, including the UK and France. In the case of regions within nations, I also found IQ associated with economic prosperity. I was conscious that this theory implied racial as well as national differences in IQs and would be highly controversial, so I opted to sit on it for a while and collect more data to be confident that it was right. I began publishing papers on this in 1977, when I estimated the IQ in Japan at 106.6 (compared to an American mean of 100), and the IQ of the Chinese in Singapore at 110. The next year I published a review of national and racial IQs.

During the following years I continued to collect IQs for countries and races from all over the world. I concluded that with the average IQ of Europeans set at 100, Northeast Asians have an IQ of 106, Southeast Asians have an IQ of 90, Native American Indians have an IQ of 89, and sub-Saharan Africans have an IQ around 70. In 1980, I published these results and my theory that these race differences evolved when early humans migrated out of Africa into temperate and then into cold northern environments. I proposed that these environments were more cognitively demanding, and so the peoples who settled in North Africa and South Asia, and even more so the Europeans and the Northeast Asians, had to evolve higher IQs to survive.

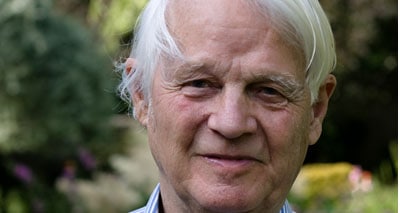

In 2000, I met Tatu Vanhanen, a political economist in Finland, and we discussed working together on the contribution of the national IQs I had collected to the economic development of nations. We published our conclusions in 2002 in IQ and the Wealth of Nations. This gave IQs for 185 nations, consisting of all nations whose populations were greater than 50,000 in 1990, and found a correlation between national IQ and per capita real GDP in 1998 of .63.We argued that national IQs are the single most important variable in determining national per capita GDP, and we proposed that the other factors are largely the degree to which nations have free market economies, and the presence of natural resources such as oil.

Tatu Vanhanen

I sent a copy of our book to the Economist, but they did not review or mention it. Others gave it a mixed reception. Susan Barnett and Wendy Williams (2004) described national IQs as “virtually meaningless,” and Earl Hunt and Robert Sternberg (2006) called them “meaningless.” However, Earl Hunt later changed his mind, because in his text book Human Intelligence (2011, p. 440) he wrote, “Lynn and Vanhanen’s conclusions about the correlations between IQ estimates and measures of social well-being are probably correct.”

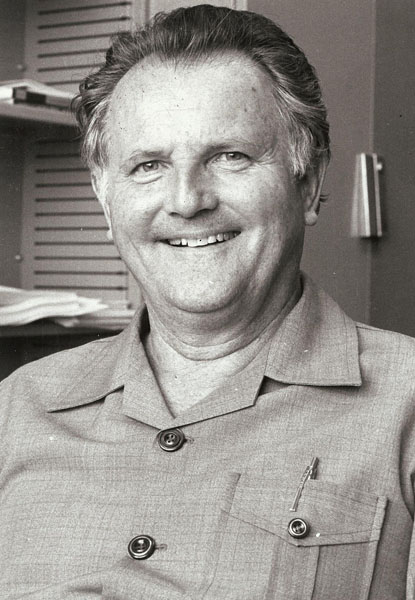

Did the work of men such as Arthur Jensen, Hans Eysenck, and Cyril Burt influence you at that time?

RL: Sure, they were my three role models in psychology. I knew Hans Eysenck well from 1957 onwards, and worked with him on several projects. I was greatly influenced by Art Jensen. When I was a student at Cambridge in the 1950s, we were told that the low IQs of blacks in the United States were due to social deprivation and discrimination. This was the almost universally accepted view, promulgated by experts like Ashley Montagu and Theodosius Dobzhansky, and I saw no reason to doubt it. It was Art Jensen’s now famous 1969 paper in the Harvard Educational Review that first began to make me question this. Jensen concluded that there is likely to be a genetic difference underlying the black-white IQ difference. His actual words were that it is “a not unreasonable hypothesis that genetic factors are strongly implicated in the average Negro-white intelligence difference” (p.82). I read the paper carefully and thought Jensen made a good case. Two years later, the same conclusion was reached by Hans Eysenck, whose judgement I had come to respect, in his book Race, Intelligence and Education (1971). Jensen presented further evidence in his 1973 book, Educability and Group Differences and confirmed my view that he was right.

I came to know Art Jensen well from the 1970s. Apart from being very able, he could be very amusing and was an excellent raconteur. I once asked him how he came to marry his wife Barbara. He said he had noticed her doing a good job looking after the monkeys in the animal lab at UC Berkeley, and he reckoned that she would be equally good at looking after him. He said he was a bit concerned that she liked socializing but said “I was able to cure her of that.” I once asked him why he did this work on race differences in IQs that attracted so much hostility. He replied that he thought it was because he did not much mind being disliked. I think this must have been right. Most people have a strong “herd instinct” as it used to be called, that makes them terrified of being disliked and excluded from the herd. I am like Art Jensen in having a weak herd instinct.

Arthur Jensen

I also knew Cyril Burt, whom I met first in rather intimidating circumstances when he was my examiner for my Ph.D. We corresponded subsequently on cordial terms on a number of occasions and he was always very helpful.

I was also influenced by William Shockley who, in the late 1960s, began supporting the view that the black-white IQ difference has a genetic basis. As a Nobel Prize winner, his views generated a lot of publicity and respect, although I don’t think he made any significant scientific contribution to the issue.

And who among your contemporaries do you value most?

RL: I have published papers with Helen Cheng at University College, London, Roberto Colom at the Autonomous University in Madrid, Andrei Grigoriev at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, Satoshi Kanazawa at the London School of Economics and Gerhard Meisenberg at Ross Medical University in Dominica. I am indebted to all of these for their invaluable contributions to the work we have done together. In addition, I have had many fruitful discussions with Edward Miller, Jan te Nijenhuis, Helmuth Nyborg and James Thompson.

Was your work in the late 1970s the first serious scholarship on the intelligence of the Japanese? For centuries, whites had noticed the generally low intelligence of Africans, but had any scientists concluded that East Asians were more intelligent than whites?

RL: No, curiously Francis Galton did not include the intelligence of the Japanese or other Northeast Asians in his Hereditary Genius (1868), in which he quantified the intelligence of Africans as much lower than that of whites, and of Australian Aborigines as lower than that of Africans. I was the first to publish work on the high intelligence of Japanese. This was a shock for environmentalists, many of whom argued that whites performed better than other races on intelligence tests because whites devised the tests to suit their particular skills, and that other races would be more intelligent than whites in their own environments. Einstein is reported as having said that he would be much less intelligent than Australian Aborigines in the Australian outback. My work showing that the Japanese performed better than whites on intelligence tests designed by whites was a setback for this position. When I met Phil Rushton some years later he told me that reading my work on the high IQ of the Japanese was one of the things that led him to formulate his theory of Mongoloid-Caucasoid-Negroid r-K differences.

Philippe Rushton

In 1982, you reported that Japanese IQs had risen rapidly since the 1930s, and in 1987 you found similar IQ gains in Britain. These broad gains have since been called the Flynn Effect, but since you were the first to discover them, should they not be called the Lynn Effect?

RL: It was Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray who called these IQ gains “the Flynn Effect” in their book The Bell Curve (1994). Richard Herrnstein sent me the book before publication for my comments, and I replied that it was all splendid except that I could not understand why they had designated the increases in intelligence that had been recorded in several countries from the 1940s onwards as “the Flynn Effect,” after Jim Flynn who published a couple of papers on it in 1984 and 1987. I suggested it should be called the “Tuddenham effect” after the author of the first major study on this subject in 1948, in which he showed that the IQ of American military conscripts increased from World War I to World War II. They took no notice of my suggestion.

I had reported an increase in the Japanese IQ in 1982 and some people have called the rise “The Lynn-Flynn effect,” but many people now believe and assert that the increase was discovered by Jim Flynn, who rediscovered it in 1984. In 2013, I published a paper “Who discovered the Flynn Effect? A review of early studies of the secular increase of intelligence,” which summarized about 30 studies from the mid-1930s onwards that had reported increases in numerous countries.

Left to right: Philippe Rushton, Helmuth Nyborg, Jim Flynn, Richard Lynn, and Satoshi Kanazawa.

Is the gain real?

RL: I find it is a difficult question to answer. On the positive side, intelligence tests seem to be a sound measure of IQs and measured IQs have increased quite a lot. On the negative side, Michael Woodley, Jan te Nijenhuis and Raegan Murphy, for whom I have a great respect, believe the gain is not real because they have shown reaction times have become slower during the last century. So I remain open-minded on this question.

You argue that nutrition accounts for most of the rise. What is your basis for this view?

RL: I wrote a long paper in 1990 (“The role of nutrition in secular increases of intelligence”) presenting the evidence for this. The main points are that the quality of nutrition undoubtedly affects intelligence and that the quality of nutrition improved during the 20th century, as shown by increases in height. The rise came to a stop in several countries including Norway, Denmark, and Britain in the early 21st century and has now gone into decline most likely because of dysgenic fertility (see below).

Who are the rising stars in the field of intelligence research today?

RL: I would particularly nominate Heiner Rindermann, Davide Piffer, Michael Woodley, and Edward Dutton. Heiner Rindermann in Germany is a risen rather than a rising star, who has done brilliant work contributing to my collection of national IQs and fine-tuning them, in particular by showing that the IQ of the top 5 percent of a nation makes a more important contribution to economic development than the average IQ.

Davide Piffer has done brilliant work identifying the genes responsible for race differences in intelligence. He is from the north of Italy where the more intelligent Italians are found.

Michael Woodley is a brilliant young Englishman who has published numerous papers on a wide variety of topics, and Edward Dutton is another brilliant young Englishman who has published some excellent work on race differences in sporting abilities.

Sex differences in intelligence are as controversial as race differences. You have written that the average adult male IQ is four points higher than the average adult female IQ. What is the evidence for this view?

RL: I have written quite a lot about this. In all fields of scholarship we have to take a lot on trust. If all previous scholars are agreed on something, we take it for granted that they must be right. All the experts from at least World War I on had stated that there is no sex difference in intelligence, and many scholars whom I respected repeated this assertion. For instance, Herrnstein and Murray wrote in The Bell Curve that “The consistent story has been that men and women have nearly identical IQs.” I had no reason to doubt this consensus, but in 1992 I was shaken when Dave Ankney and Phil Rushton independently published papers showing that men have larger brains than women, even when controlling for body size and weight. These results presented a problem. It is well established that brain size is positively related to intelligence at a correlation of about 0.4. As men have larger brains than women, it seemed to follow that men should have a higher average IQ than women. Yet all the experts were agreed that men and women have the same intelligence.

I grappled with this problem for about six months. I went through dozens of studies, and the experts seemed to be right that males and females have the same intelligence. Then at last I found what I believed to be the solution. When I looked at the studies in relation to the age of the subjects being tested, I found that males and females do have the same intelligence up to the age of 15 years, as everyone had said. But I found that from the age of 16 years onward, males begin to show higher IQs than females, and that by adulthood, the male advantage reaches about four IQ points, entirely consistent with their larger average brain size. I proposed that the explanation was that males continue to mature from the age of 16 years, while the maturation of females stops. I published this solution to what I called the Ankney-Rushton anomaly in 1994.

Most people ignored my solution, including Art Jensen in his 1998 book The g Factor. He concluded that “the sex difference in psychometric g is either totally non-existent or is of uncertain direction and of inconsequential magnitude.” I continued to publish papers showing that up to the age of 15 years males and females have approximately the same IQ except for a small male advantage on the spatial and visualization abilities, but from the age of 16 males begin to show greater intelligence, but most people continued to assert that men and women have equal intelligence. For instance, in 2006, Stephen Ceci and Wendy Williams published an edited book Why aren’t more women in Science? They brought together 15 experts to discuss this question. They began by saying “We have chosen to include all points of view,” but none of the contributors presented the case that men have higher intelligence than women, and that high intelligence is required to make a successful career in science. Several of the contributors asserted that there are no sex differences in intelligence.

The only person who attacked my theory was Nick Mackintosh. In 1996, he contended that the Progressive Matrices is an excellent measure of intelligence and of Spearman’s g, that it is known that there is no sex difference in scores on the Progressive Matrices, and therefore that my claim was refuted. He made no mention of my maturation theory, namely, that it is only from the age of 16 years that males begin to show higher IQs than females. In response to Mackintosh’s criticism I collaborated with Paul Irwing in carrying out meta-analyses of sex differences on the Progressive Matrices in general population samples and in university students. We found that in general population samples there is no sex difference up to the age of 15 years, but among adults, men have a higher IQ than women by 5 IQ points. Among university students, we found the male IQ advantage is 4.6 IQ points.

While most experts ignored our results, I did have some supporters for my conclusions. In the next few years several people published data supporting the theory, including Helmuth Nyborg, Juri Allik, Doug Jackson, Phil Rushton, Roberto Colom, and Gerhard Meisenberg. By 2016, many studies have shown that men have a higher IQ than women. Nevertheless, some scholars continue to assert that there is no sex difference in intelligence. For instance: “Women tend to do better than men on verbal measures, and men tend to outperform women on tests of spatial ability; these small differences balance out so that the average general score is the same” (Ritchie, 2015, p. 105). Likewise: “In adulthood, there is scant evidence for sex differences in g, although women tend to perform better than men in verbal tasks, whilst men outperform women slightly in spatial tasks” (Cooper, 2015, p.207). The assertion that women tend to perform better than men in verbal tasks is incorrect and it is astonishing that some scholars are making this contention. The only explanation would seem to be that they have never read the literature on this issue.

Why is the study of group differences so controversial? In particular, why do whites so strongly resist the rather obvious fact that they are, on average, more intelligent than blacks?

RL: Whites have become so nice and sensitive to the feelings of others that they hate to accept that some individuals and peoples are more intelligent than others. Denial of these differences has become known as political correctness. Denial has become so strong that intelligence has even become a taboo word. Here in Britain, children lacking in intelligence who were formally described as imbeciles and then as mentally retarded are now designated as having “special needs.” This sensitivity to the feelings of others has evolved over the last two centuries and first appeared in Britain in 1807 with the abolition of the slave trade and in 1834, with the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire. It appeared in the United States in 1865 with the abolition of slavery, and later with the abolition of slavery in Brazil. Just why whites have become so sensitive to the feelings of others is difficult to explain.

Society punishes people who break taboos. Have you faced opposition in your career?

RL: I encountered a certain amount of hostility when I was at the University of Ulster from students disrupting my lectures and demanding my dismissal but it could have been much worse.

What are your hobbies, pastimes, pleasures?

RL: My main pastime is bridge which I find is so potentially addictive that it could take over my life if I allowed it. As it is, I ration myself to two evenings a week. I get a great deal of pleasure from novels (my favorites are those of Tom Wolfe) and classical music (my favorites are the middle and late works of Beethoven). My other pleasure is my extended family, including nine grandchildren and a great-grandson. I would have been hugely disappointed if I had not had children and not passed on my genes to succeeding generations. When I read, all too often, of successful people, and especially the many successful women, who are childless, I think “what a wasted life.”

Of your many books, which do you think are the most important? If someone were to read just three books by Richard Lynn, which ones should he choose?

RL: Difficult question but I would nominate (1) Lynn, R. & Vanhanen, T. (2012). Intelligence: A Unifying Construct for the Social Sciences. London: Ulster Institute for Social Research.

This was our last work on national IQs and their numerous educational economic, sociological, demographic, geographical and climatic causes and effects.

(2) Lynn, R. (2015). Race Differences in Intelligence: An Evolutionary Analysis. Second edition. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers. This documents racial IQs worldwide and explains how they evolved.

(3) Lynn, R. (2016). Race Differences in Psychopathic Personality. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers (not yet published). This book documents racial differences in psychopathic personality worldwide, showing that they are the reverse of those in intelligence–highest in Australian Aborigines and lowest in Northeast Asians–and explains how they evolved. This is a book-length treatment of the theory I set out in a paper in 2002.

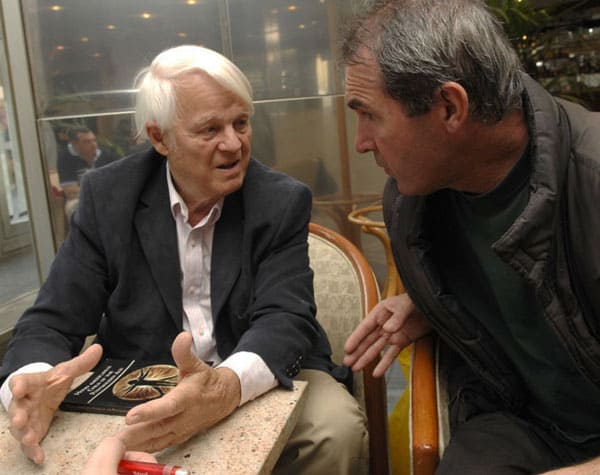

Richard Lynn and Tom Sunic

Are there other books you would like to mention?

RL: The Global Bell Curve (2005) took as its starting point The Bell Curve, in which Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray showed in 1994 that in the United States there is a racial hierarchy in which Europeans have the highest IQs and perform best in earnings, socio-economic status, and a range of social phenomena, Hispanics come next, while blacks do least well. In The Global Bell Curve I examined whether similar racial intelligence and socio-economic hierarchies are present in other parts of the world, and documented that they are. They are found in Europe, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, Australia and New Zealand. It is invariably the Europeans and Northeast Asians who are at the top of the racial hierarchies. These are followed by the brown-skinned peoples who occupy intermediate positions, e.g. the Coloreds and Indians in Africa, the Mulattoes and Mestizos in Latin America, and light-skinned blacks in the United States, who are in the middle of the IQ and socio-economic hierarchies. Dark-skinned African Blacks and Native American Indians invariably are at the bottom of the hierarchies.

In Australia and New Zealand, it is the lighter-skinned Europeans and Chinese who are at the top of the IQ and socio-economic hierarchies, while the darker-skinned Aborigines and Maoris are at the bottom. In Southeast Asia, in Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Thailand, it is invariably the Chinese who have higher IQs than the indigenous peoples and outperform them in education, earnings, wealth, and socio-economic status.

These color-related social hierarchies are so inescapable that sociologists and anthropologists have coined the term pigmentocracy to describe them. A pigmentocracy is a society in which wealth and social status are related to skin color. I argued that intelligence differences provide the best explanation for the racial hierarchies that are present in all multiracial societies.

I would also like to mention my work on dysgenics and eugenics. I became interested in eugenics when I was a student in the 1950s. I read the papers of several psychologists in the United States, and of Sir Cyril Burt, Sir Godfrey Thompson and Ray Cattell in Britain, showing that the average IQ of the population was declining because people with low IQs were having more children than those with high IQs. I thought this must be an enormously serious problem. But it was not until the early 1990s that I began to work on eugenics.

My first book on this subject was Dysgenics (1996), which described the deterioration of genetic intelligence in many economically developed nations caused by the lower fertility of those with high IQs, especially women. It sets out the evidence that modern populations have been deteriorating genetically from around 1880 in terms of health, intelligence and moral character.

In 2001, I published a sequel, Eugenics: A Reassessment. It begins with a historical introduction to the ideas of Francis Galton and the rise and fall of eugenics in the 20th century. I then discuss the objectives of eugenics, which I identify as the elimination of genetic diseases and the improvement of intelligence and moral character. This is followed by a consideration of how eugenic objectives can be achieved using methods of selective reproduction and concludes that there is not much scope for this.

Finally, I discuss how eugenic objectives could be achieved by the “New Eugenics” of biotechnology using embryo selection and how these are likely to be developed in the 21st century. I conclude by predicting the inevitability of a future eugenic world in which couples will select genetically desirable embryos for implantation and there will be huge improvements in the genetic quality of the populations of economically developed countries where these technologies are adopted. I have also published several papers demonstrating dysgenic fertility for intelligence in the United States and Britain, and one showing that there is also dysgenic fertility for moral character.

There is also my book on the high IQ of the Jews: The Chosen People: A Study of Jewish Intelligence and Achievements (2011). I was stimulated to write this because some years ago I read that about a third of the Nobel Prizes won by Germany in the years 1901–1939 had been awarded to Jews. I found that Jews were about 0.85 per cent of the population, and reflected that Jews must have had a very high IQ to achieve this astonishing over-representation. I had a look at the research on the intelligence of the Jews and found that a number of studies had been published reporting that Jews do indeed have high IQs. They were all quite old, since comparative studies of the IQs of different peoples have become increasingly taboo. I investigated the Jewish IQ, and estimated the Ashkenazi IQ at approximately 110, and the IQ of Oriental Jews at 91. I also wondered whether Jews might have some personality characteristic, such as a strong work ethic, which might contribute to their high achievements, but in a paper I published in 2008 with Satoshi Kanazawa we reported that we could find no evidence for this.

I then read a number of papers in economics and sociology journals going back to the first half of the 20th century on the educational attainments, earnings and socio-economic status of Jews in the United States, and found that these are all higher in Jews than in gentile whites. But the strange thing was that none of these mentioned that the explanation for these remarkable achievements could be high intelligence. The more of these papers I read, the more it became apparent that work needed to be done investigating whether high Jewish IQ explains their high educational attainments, earnings, and socio-economic status in all countries in which they are, or have been, present. I have documented that this is so in my book, The Chosen People: Jewish Intelligence and Achievements.

It may be surprising that the book was largely ignored by Jewish academics and intellectuals. It was not reviewed in the Jewish journal Commentary or in the Jewish Journal of Sociology. It seems Jews have become so politically correct that they have become embarrassed by their high IQ and their huge contributions to knowledge.

And finally there is my Race and Sport: Evolution and Racial Differences in Sporting Ability (2015, written jointly with Edward Dutton) which documents that there are some sports at which blacks are better than Europeans and Northeast Asians, notably sprinting in the case of West Africans and long distance running in the case of east Africans. I thought it was time to show that there are some things at which blacks are better than whites, though I believe that in the United States people have been dismissed from their jobs for saying this.

Given your view on dysgenics and racial differences in IQ, what future do you see for the West?

RL: I am very pessimistic about the future of the West. I think there are four problems. First, our populations are declining because we have below replacement fertility in all Western nations. Second, we have dysgenic fertility, i.e. high-IQ women are having fewer children than low-IQ women, with the result that the genetic IQ of our populations is declining.

Third, most Western countries have been experiencing massive immigration of non-Western peoples who will eventually become majorities. In the United States, the European peoples will become a minority around the year 2042 and a declining minority thereafter. The United States will inevitably become like Latin America and resemble Mexico, Venezuela, and other Latin American countries, and cease to be a superpower. The replacement of Europeans by non-Europeans is also taking place throughout Western Europe. In Britain, non-Europeans are expected to become a majority around the year 2066, and in other Western European countries some time in the second half of the century. I believe this demographic transition is unstoppable because of continuing non-European immigration and the high fertility of the immigrants.

Fourth, in the world as a whole there is much higher fertility in the low IQ countries. The effect of this is that the world’s IQ is deteriorating genetically and there is every reason to expect that this deterioration will continue for many decades.

This is certainly a pessimistic scenario. Do you see any cause for optimism?

RL: Yes. First, Western Civilization will probably survive in Eastern Europe and Russia and in Israel, at least for a while, as these countries are fairly successful at preventing the immigration of non-Western peoples. Second, China, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea have highly intelligent populations and are also preventing the immigration of non-indigenous peoples. I believe that these countries will carry the torch of civilization and within a few decades China will replace the United States as the world superpower. Whether this is an optimistic scenario I will leave others to decide.

How do you hope to be remembered?

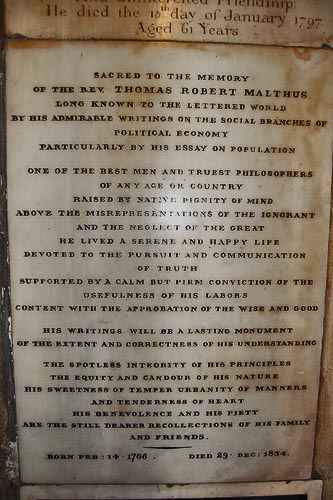

RL: As one who made some contribution to advancing the understanding of truths that were politically incorrect but scientifically correct–like my fellow Englishman Thomas Malthus, who was buried in 1834 in Bath Abbey, about 15 miles from where I live. His memorial tablet in the Abbey reads as follows:

Thomas Malthus was one of the best men and truest philosophers of any age or country raised by native dignity of mind above the misrepresentations of the ignorant and the neglect of the great. He lived a serene and happy life devoted to the pursuit and communication of truth supported by a calm but firm conviction of the usefulness of his labours, content with the approbation of the wise and good. His writings will be a lasting monument of the extent and correctness of his understanding. The spotless integrity of his principles, the equity and candour of his nature, his sweetness of temper, urbanity of manners, tenderness of heart, and his benevolence are the recollections of his family and friends.

Allik, J., Must, O and Lynn, R. (1999). Sex differences in general intelligence among high school graduates: Some results from Estonia. Personality and Individual Differences, 26, 1137-1141.

Ankney, C.D. (1992) Sex differences in relative brain size: the mismeasure of women, too? Intelligence, 16, 329-336.

Barnett, S. M. & Williams, W. M. (2004). National Intelligence and the Emperor’s New Clothes: A Review of IQ and the Wealth of Nations, by Richard Lynn and Tatu Vanhanen. Contemporary Psychology, 49, 389-396.

Ceci, S.J., & Williams, W. (Eds.) (2006) Why aren’t more women in Science? Top researchers debate the evidence. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Colom, R. & Lynn, R (2004). Testing the developmental theory of sex differences in intelligence on 12-18 year olds. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 75-82.

Cooper, C. (2015). Intelligence and Human Abilities. London: Routledge.

Dutton, E. & Lynn, R. (2015). Race and Sport: Evolution and Racial Differences in Sporting Ability. London: Ulster Institute for Social Research.

Flynn, J.R. (1984). The mean IQ of Americans: massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 29-51.

Herrnstein, R. & Murray, C. (1994). The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: The Free Press.

Hunt, E. (2011). Human Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R.J. (2006). Sorry, wrong numbers: An analysis of a study between skin color and IQ. Intelligence, 34, 131-139.

Irwing, P. & Lynn, R (2005). Sex differences in means and variability on the Progressive Matrices in university students: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychology, 96, 505–524.

Jackson, D.N. & Rushton, J.P. (2006). Males have greater g: Sex differences in general mental ability from 100,000 17-18 year olds on the Scholastic Assessment Test. Intelligence, 34, 479-486.

Jensen, A. R. (1998). The g factor: The science of mental ability. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Lynn, R. (1977a). The intelligence of the Japanese. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 30, 69-72.

Lynn, R. (1977b). The intelligence of the Chinese and Malays in Singapore. Mankind Quarterly, 18,125-128.

Lynn, R (1982). IQ in Japan and the United States shows a growing disparity. Nature, 297, 222-223.

Lynn, R. (1990). The role of nutrition in secular increases of intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 273–285.

Lynn, R. (1994). Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: A paradox resolved. Personality and Individual Differences, 17, 257-271.

Lynn, R. (1996). Dysgenics: Genetic deterioration in Modern Populations. Westport, CT., Praeger.

Lynn, R. (2001). Eugenics: A Reassessment. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Lynn, R. (2002). Racial and ethnic differences in psychopathic personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 273-316.

Lynn, R. (2008). The Global Bell Curve. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers.

Lynn, R. (2013). Who discovered the Flynn Effect? A review of early studies of the secular increase of intelligence. Intelligence, 41, 765-769.

Lynn, R. (2015). Race Differences in Intelligence: An Evolutionary Analysis. Second edition. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers.

Lynn, R. (2016). Race Differences in Psychopathic Personality. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers.

Lynn, R. & Harvey, J. (2008). The decline of the world’s IQ. Intelligence, 36, 112-120.

Lynn, R. & Irwing, P. (2004). Sex differences on the Progressive Matrices: A meta-analysis. Intelligence, 32, 481-498.

Lynn, R. & Kanazawa, S. (2008). How to explain high Jewish achievement: The role of intelligence and values. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 801-808.

Lynn, R. & Vanhanen, T. (2002). IQ and the Wealth of Nations. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Lynn, R. & Vanhanen, T. (2006). IQ and Global Inequality. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers.

Lynn, R. & Vanhanen, T. (2012). Intelligence: A Unifying Construct for the Social Sciences. London: Ulster Institute for Social Research.

Mackintosh, N.J. (1996). Sex differences and IQ. Journal of Biosocial Science, 28, 559-572.

Meisenberg, G. (2009). Intellectual growth during late adolescence: Effects of sex and race. Mankind Quarterly, 50, 138-155.

Nyborg, H. (2005). Sex-related differences in general intelligence: g, brain size and social status. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 497-510.

Rindermann, H. & Ceci, S. J. (2009). Educational policy and country outcomes in international cognitive competence studies. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 4, 551-577.

Ritchie, S. (2015). Intelligence. London: John Murray Learning.

Rushton, J.P. (1992) Cranial capacity related to sex, rank and race in a stratified sample of 6,325 military personnel. Intelligence, 16, 401-413.

Woodley, M. A., te Nijenhuis, J. & Murphy, R. (2013). Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time. Intelligence, 41, 843-850.