The Bad, the Ugly, and the Good, Part II

Wilburn Sprayberry, American Renaissance, September 13, 2013

In Part I, Mr. Sprayberry explained how modern historians are trying to delegitimize the “Anglo” conquest of Texas, and reviewed one of the more repulsive of the recent anti-white books. In this concluding essay, he reviews two more books on Texas history, one merely bad and the other good. He concludes with observations about how history is taught.

The bad

Gary Anderson, The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in The Promised Land, 1820 — 1875, University of Oklahoma Press, 2005, $29.95 (hardcover), 494 pp.

The racial prejudices of 19th-century Texans, who came predominantly from the slaveholding South and feared both slave conspiracy and slave revolt, led them to expect people of other races to conspire against them. Such a worldview distorted Texas history: Indians, brutal and bloodthirsty, were always at fault, and Texas Rangers were saviors. . . . Such a historical interpretation — written by the first two generations of Texas historians — is mythology.

-Gary Anderson

By contrast, Gary Clayton Anderson, a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma, is a decent writer and a competent historian. He has done solid work in the past, including The Indian Southwest 1580-1830, which sheds new light on the origins of early Texas and Southwest Indian groups.

But the purpose of his 2005, The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1820 — 1875, is virtually identical to that of Exodus from the Alamo (see Part I). Prof. Anderson maintains that the central event of 19th-century Texas is the “ethnic cleansing” of Indians, a term Prof. Anderson prefers over the more usual “genocide.” He argues that whites had no right to expand westward:

Texas was not a wilderness open for the taking. American Indians lived in Texas, and they wished to preserve their claim to this land for the benefit of their progeny. To be sure, the Texas tribes had experienced many evolutionary changes. The initial, indigenous inhabitants — Jumanos, Coahuiltecans, Tonkawas, Karankawas, Apaches, and Caddos — had faced decline and, in some cases, near extinction.

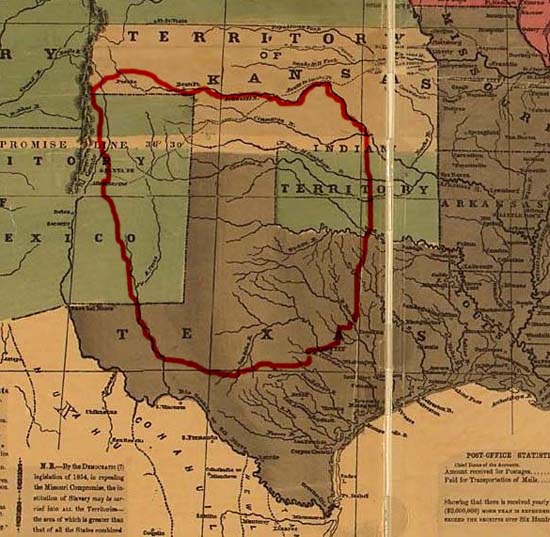

Texas actually was a wilderness “open for the taking,” but the people doing the taking — until the arrival of Anglo settlers in the 1820s — were the Comanches. It was Comanches who pushed out the groups Prof. Anderson identifies above. Starting in the second half of the 18th century, they invaded Texas from the northwest. In exceptionally brutal fighting, they defeated the tribes already living there, absorbing some, exterminating others, and driving still others — such as the Apaches — into deserts and other marginal areas.

The Comanches also wiped out several Spanish outposts, raiding so aggressively that the Hispanic population of Texas — only 3,000 to begin with — dropped by one-fourth by the beginning of the 19th century. As Pekka Hamalainen points out in Comanche Empire, the Comanches were so powerful they reduced the Spanish provinces of New Mexico and Texas to tributary status. In other words, by the time white Americans entered Texas, the dominant Indians in the region were themselves conquering newcomers.

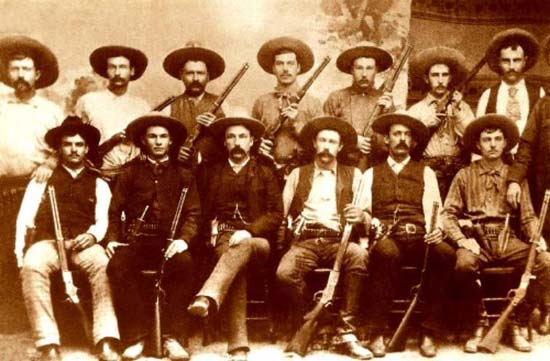

To Prof. Anderson, however, the typical Anglo settler was greedy, boorish, and violent, combining the traits of a burglar and squatter, and justifying his behavior with a generous dose of racism. The Conquest of Texas isn’t so much a history book as an indictment against the traditional heroes of Texas history, especially the Texas Rangers. Although Prof. Anderson acknowledges some ranger units were “. . . fine troops: well mounted, well led, and disciplined,” this is how he describes the majority:

Filled with hatred and malice, members of such groups seldom took prisoners or even asked whether the Indians they attacked were friendly or hostile. . . . more often than not [Rangers were] brutal murderers.

Anderson flays the Rangers for atrocity after atrocity. Along the way he excoriates Walter Prescott Webb, the most famous historian of the Rangers, for excusing such behavior “as part of nation building” and as of “the story of the American frontier.”

It is true that Rangers sometimes committed atrocities, but Prof. Anderson does not acknowledge that atrocities had been part of Indian warfare — on both sides — since the early 17th century. What happened in Texas cannot be seen in isolation from what had been happening on the American frontier for two centuries before that: raid and counter-raid. Indians burn homesteads and butcher white families; whites then destroy Indian villages, often killing at least some of the women and children.

Like so many PC historians, Prof. Anderson is guilty of “presentism.” He judges the past by the standards of the present, and condemns anyone who don’t measure up. The Anglo pioneers of Texas, many of whom were “born fighting” to use James Webb’s phrase, should not be judged by the standards of 21st century liberalism.

What about the murders of white settlers? Prof. Anderson blames white outlaws, who he says slaughtered white families as well as innocent Indians. Whenever the primary sources express doubt about the identity of the perpetrators, Prof. Anderson assumes they were white outlaws rather than Indians. Any source who blames Indians he dismisses as an unreliable “Indian hater.”

It is certainly true that Indians did not cause all the frontier violence. There were plenty of bad white men, Mexicans, half-breeds, and others stealing livestock and killing people. Earlier historians, including Mr. Fehrenbach and Walter Prescott Webb, wrote about this decades ago. However, these older historians failed to show enough contrition, and their work can be disregarded.

Prof. Anderson simply ignores important sources that do not support his conclusions. Two of these are Noah Smithwick and Charles Goodnight. Smithwick was a blacksmith who fought in the Texas Revolution and early ranger companies, and Goodnight was a ranger who invented the cattle drive. Both left memoirs that are considered indispensable sources for life on the frontier — until the rise of PC — and are rich in details about Indian attacks. It is clear that the reality of Indian attack was the single most important fact of frontier life.

But what was perhaps worst about the Anglos is that they did not appreciate “diversity:”

Texans never agreed to accept the existence of western Plains Indians in the state under any circumstances. It was this denial, this refusal to accept ethnic diversity . . . that condemned Texas to a history of violence and instability.

In fact, if there is anything good to say about The Conquest of Texas, it is that Prof. Anderson succeeds in showing how incredibly complex and diverse a place early Texas was, with scores of different Indian tribes, Mexicans, half-breeds, escaped slaves, outlaws, renegades, adventurers, and Anglo settlers, all jostling for space and contending for dominance. Naturally, Prof. Anderson fails to see that it was the lack of diversity among the Anglos — their racial solidarity — that enabled them to defeat the other groups that together greatly outnumbered them.

Far from condemning Texas to a history of violence and instability, this “refusal to accept ethnic diversity” eventually created a peaceful, stable and prosperous society that is the envy of the more “diverse” but blighted societies Prof. Anderson reveres.

The author’s inability to face facts or use sources that undercut his assumptions make The Conquest of Texas a bad book.

The good

Sam C. Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, Scribners, 2010, $16.00 (paperback) 371 pp.

It is interesting to note Texas’s peculiar position here: neither of these enemies would have accepted peace on the terms the new republic would have offered them. Even more remarkably, neither would accept surrender. The Mexican army consistently gave no quarter, most famously at the Alamo. All Texan combatants were summarily shot. The Comanches, meanwhile, did not even have a word for surrender. . . . it was always a fight to the death. In this sense, Texans did not have the usual range of diplomatic options. They had to fight.

-S. C. Gwynne

Exodus from the Alamo and The Conquest of Texas are not the only kind of history even in the age of PC. Empire of the Summer Moon is very different. The story revolves around Quanah Parker, the last great Comanche war chief. Parker was the half-white son of Cynthia Ann Parker, who at age 9 was kidnapped by Indians after a raid in which many of her family were killed. Although the story has been told many times before (it is still known by many Texas schoolchildren, and inspired the movie The Searchers), Mr. Gwynne tells the tale of Cynthia Ann Parker and her son with such skill that Empire reads like high adventure. The book has become a best seller–the most popular Texas history book since Lone Star. More wide ranging than a biography, it’s an excellent primer on Comanche history, the Anglo settlement of Texas, and the collision between two peoples.

Unlike academics who view Indians and Mexicans as good and whites as bad, Mr. Gwynne (like Mr. Fehrenbach, he is a journalist) presents a more balanced picture. He even sees similarities between the Comanches and the pioneers:

Both . . . had for the previous two centuries been busily engaged in the bloody conquest and near-extermination of Native American tribes. Both had succeeded in hugely expanding the lands under their control.

Although highly critical of what he sees as Anglo racism and rapaciousness towards the Indians, Mr. Gwynne is unsparing in his depiction of Indian savagery towards whites. One of many bloody episodes he describes is what happened to three fugitives from the raid in which Cynthia Ann Parker was kidnapped:

All three were surrounded and stripped of all their clothing. One can only imagine their horror as they cowered before their tormentors on the open plain. The Indians then went to work on them, attacking the old man with tomahawks, and forcing Granny Parker, who kept trying to look away, to watch what they did to him. They scalped him, cut off his genitals, and killed him . . . Then they turned their attentions to Granny, pinning her to the ground with their lances, raping her, driving a knife deep into one of her breasts, and leaving her for dead. They threw Elizabeth Kellogg on a horse and took her away.

Gary Anderson describes the same raid in The Conquest of Texas without giving any of the grisly details. Indeed, Indian violence against pioneers is either expurgated or euphemized in most recent history books. In the PC era, it’s not only newspapers and television stations that censor reports of atrocities against whites.

However, the most important way in which Empire of the Summer Moon differs from PC history is how it depicts whites themselves. They are shown, not as the slave-whipping, Mexican-oppressing, Indian-murdering caricatures one now sees in countless movies and TV shows, but as:

. . . simple farmers imbued with a fierce Calvinist work ethic, steely optimism, and a cold-eyed aggressiveness that made them refuse to yield even in the face of extreme danger. They were said to fear God so much that there was no fear left over for anyone or anything else. . . . They, more than columns of dusty bluecoats, were what conquered the Indians. [The Parker family] offers a nearly perfect example of the sort of righteous, up-country folk who lived in dirt-floored, mud-chinked cabins, played ancient tunes on the fiddle, took their Kentucky rifles with them into the fields, and dragged the rest of American civilization westward along with them.

Although one can quarrel with Mr. Gywnne’s occasional use of purple prose and overuse of superlatives, Empire of the Summer Moon is a very good book. The story it tells is so dramatic, exciting, and tragic it’s hard to put down. For anyone interested in how Texas got to be Texas, Empire is a far better place to start than Exodus from the Alamo or The Conquest of Texas.

The future of history

The history of Texas was unique in North America, but never unique or even unusual in the world of man. It was an old, old story: new peoples, new civilizations impinging on the old. The reactions of these peoples — Caucasian, Amerind, and Hispanic-Mexican — were in no sense aberrations. The treatment of one culture or one race by another was always determined by relative strengths and weaknesses, and by the nature of the cultures themselves, dynamic or regressive. It was never, and probably never will be, so long as men stay men, determined by internal ethical or moral ideas and institutions. More Texans understood this, out of their history, than their compatriots who never physically or spiritually left the safety of the sheltering Appalachians.

-T.R. Fehrenbach

Since history is a story we tell about the past, I will end with two stories. (The first is from Oklahoma, but could easily be from Texas.) They reflect contrasting realities about what young white people see today as their heritage.

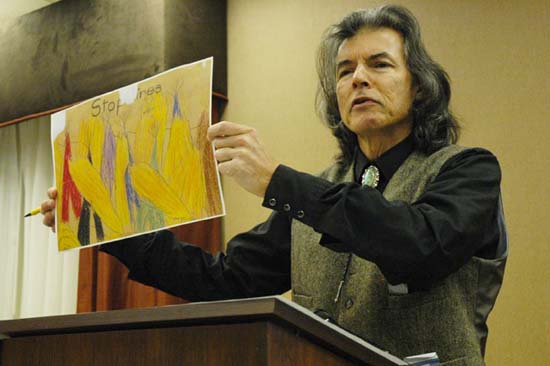

The first story comes from David Yeagley, a Comanche Indian and college professor who spoke at the 2012 American Renaissance conference. During a discussion about patriotism in one of his psychology classes, a female student — visibly upset — told him how ashamed and worthless she felt as a white person. “My race,” she said, “it’s just nothing!” Dr. Yeagley pointed out that she had taken a course from a history instructor known for haranguing students with anti-white ideas. Multiply her confusion and demoralization by the millions and you get some idea of what today’s version of American history has done to young white people.

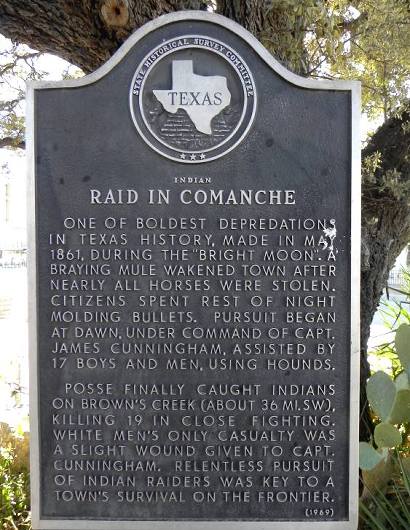

The second story comes from what I saw a few years ago in a 7th-grade Texas history class. I was observing a teacher at another school; my principal required teachers to do this as part of their professional development. The school was in an affluent, nearly all-white suburb near Dallas, and every student in this class was white. It was taught by a very young woman — no older than 25. The lesson that day was “Indian Depredations in Texas,” which she had taken from the title of an 1889 book about the Indian Wars. She read passages out of the book to her pupils which recounted, in graphic detail, the horrible mutilations and torture which Indians inflicted on their white captives. Then she read from Fehrenbach’s Lone Star about the battles between the Texas Rangers and the Comanches. The students were wide-eyed with excitement, bursting with questions, and enthralled by what they were hearing. Whatever emotion they were feeling, it wasn’t shame, or guilt or worthlessness. What their young faces showed was pride, pride in what their ancestors had endured and accomplished.

After the class I asked the teacher why she had chosen to read such violent passages. She told me her family was descended from pioneers, and that as a girl she had heard stories passed down for generations about how hard it had been on the frontier. “I want my students to know what we had to go through,” she said.

Both of these stories reflect the teaching of history in Texas — and the rest of the country. Which reality will prevail? Certainly, shame and demoralization now seem to characterize white attitudes about almost everything. I suspect there are not many history teachers like that young woman.

But there are some, and that is cause for hope. The popularity of a book like Empire of the Summer Moon is a positive sign as well.

This also brings to mind something I heard at the 2012 American Renaissance conference. As a speaker discussed the powerful forces threatening the very existence of the white race, he counseled against despair and quoted Spengler: “Pessimism is cowardice.” Texans have never been cowards. As Voltaire observed, in this world, one is either the hammer or the anvil. The Anglo-Celt pioneers who defeated the Mexicans, drove out the Indians, and made Texas a unique part of Western Civilization were the former. It remains to be seen which their descendants will be.