McCarren Pool Mayhem

Henry Wolff, American Renaissance, September 14, 2012

Most white Americans celebrate “diversity” only in the abstract. Residential and social segregation ensure little contact with non-whites, and many families change zip codes or pay private school tuition to send their children to “good” — white — schools.

Public areas like buses, subways, parks, and fair grounds are places where whites experience racial diversity. They are also where racial tension is high, and the newly renovated McCarren Park Pool in New York City is no exception. Non-whites have created such an atmosphere of violence and disorder since its reopening in June that many whites have avoided the $50 million facility.

History

At the turn of the 20th century, major cities built large public swimming pools, where Americans of all races could find relief from the summer heat. In many Northern cities such as Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York, these pools were integrated by race, but separated by sex and class.

As Jeff Wiltse explains in his book Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, it was considered inappropriate for the sexes to swim together, so they used separate pools or swam in the same pools at different times. Public swimming pools were mostly used by working-class Americans, many of whom were black or recent European immigrants. Middle- and upper-class Americans avoided the pools since they considered blacks and ethnic whites unclean, foreign, and poor, and were afraid of catching diseases from the water.

This changed in the 1920s and 1930s. Less Victorian attitudes toward sex and the improved economic status of ethnic whites turned municipal pools into melting pots for the sexes and for working- and middle-class Americans — but led to segregation of blacks.

It was one thing for blacks to swim with whites of the same sex, but whites did not want blacks around semi-clothed white women. Mr. Wiltse says this was a primary, if unstated, reason for segregating pools.

The Great Black Migration also helped change thinking in the North. From 1915 to 1930, about 1.5 million Southern blacks went north, settling in the “black belt” areas of Northern cities. Mr. Wiltse says the influx “heightened perceptions of racial difference in the North, which helped whites of all social classes forge a common identity out of their shared whiteness.” Ethnic, working-class whites also came to view blacks as a source of dirt and disease, and did not want to swim with them.

Residential segregation meant that city planners in the North could accomplish de facto what the South’s Jim Crow laws accomplished de jure. In New York City, famed Parks Commissioner Robert Moses made an effort to locate 11 Works Progress Administrations (WPA) pools in racially homogenous areas.

In Harlem, where whites, blacks, and Puerto Ricans lived in relative proximity, Moses built one pool in black Harlem’s Colonial Park and another further south in Thomas Jefferson Park, which was in a mostly white area. Moses biographer Robert Caro says that to discourage non-whites from swimming at Thomas Jefferson Pool, Moses hired only white attendants and lifeguards, and left the pool unheated, believing the cold water would keep blacks out.

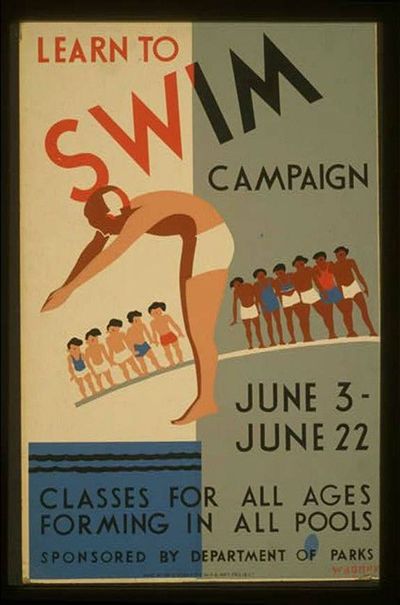

A 1940 ad by the New York Department of Parks depicts the racial separation authorities desired:

One of the city’s largest WPA pools was in McCarren Park, in working-class Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood, which was heavily Italian and Polish. At its opening in 1936, the $1 million pool could accommodate 6,800 swimmers and was as large as three Olympic-sized pools combined. A 1990 New York Times article says, “From the day it opened, it [McCarren Park Pool] became a resort for people who could not afford vacations, and was the hub of the working-class neighborhood’s summertime social life.”

Contemporary photos show swimmers were overwhelmingly white:

As the century wore on, the WPA pools, including McCarren, fell into disrepair and the clientele changed. New York State Assemblyman Joe Lentol, who grew up in Greenpoint, said that by the 1970s and ‘80s, the pool “wasn’t used as much by the white population. It was being used . . . mostly by folks coming from other neighborhoods . . . and there was a lot of discontent from residents in Greenpoint.”

In 1984, the city budgeted $6.5 million for renovations and closed the pool for repairs. Neighborhood activists, however, lobbied against renovation, saying the pool had become a haven for drug dealers, prostitutes, and rowdy teenagers. They wanted it shut down permanently. Several residents felt so strongly about the issue that they chained themselves to the construction fence, refusing to let workers in.

While researching a history of McCarren Pool, writer Grant Moser spoke with one long-time resident who boasted of being part of the effort to keep the pool closed, saying that the goal was “one way or the other, to keep the coloreds out.” This sentiment was echoed by then-Parks Commissioner Henry Stern who said:

Others, typically older white residents, complained about it [the pool]. There were racial issues. The neighborhood was afraid of violence and that the police would be unable to contain it.

Because of neighborhood opposition, city authorities kept the pool closed while they negotiated with residents. In 1986, Parks Committee chairwoman Jan Peterson held town hall meetings in Greenpoint and neighboring Williamsburg to discuss the fate of the pool. Miss Peterson says the meetings were racially charged:

There was a divide between black and Hispanics in Williamsburg and the Greenpoint general area, which included Italian and Polish. One group remembered it being it safe and nice and the other group remembered when the other group came, it became not so safe and nice.

In 1988, the community board agreed to a $15-million plan proposed by Councilman Abe Gerges which would downsize the pool to under one-third its original capacity — a move locals hoped would deter outsiders — while replacing the two bathhouse wings of the entry archway with a year-round recreation facility. The plan was stalled, however, by a group called “Independent Friends of McCarren Park” who wanted to preserve the pool’s original architecture.

Lack of funds also prevented the plan’s enactment, and Councilman Gerges, believing the pool was no longer worth saving, secured $350,000 for its demolition, causing preservationists to redouble their efforts. Some, including community board member Mildred Tuddy, said the demolition plan sounded like “racism.” That plan failed, too.

Over the next two decades, a number of other proposals to revive McCarren fell victim to community squabbling and budgetary woes as the historic pool continued to decay. At the turn of the new century, however, the neighborhood began to gentrify, and home values soared. Many older Italian and Polish residents sold and moved out while young artists and “hipsters” moved in.

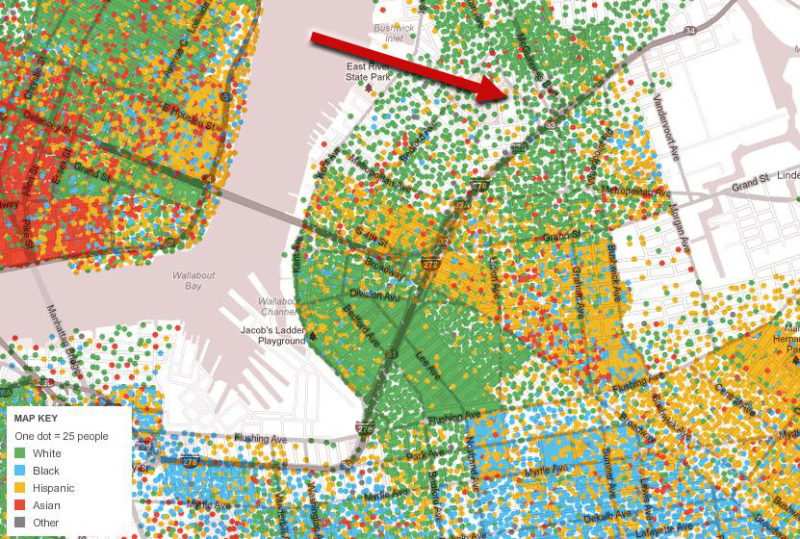

McCarren area demographics, based on 2005-2009 Census data. The red arrow points to the pool location. Source: New York Times Mapping America project.

Around 2005, the pool was temporarily converted to grounds for large-scale music concerts. Two years later, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a $50-million restoration of McCarren Pool as part of his PlaNYC initiative. In deference to community preferences, the new plan would cut the pool’s swimming capacity from 6,800 to 1,500, and convert the historic archway and wings to changing rooms and a year-round recreation center. It faced little opposition and construction began two years later.

A new era?

Hopes were high when McCarren Park Pool reopened on June 28, 2012, after 28 dry years. The New York Times says the unveiling was “hailed as a grand civic achievement and, perhaps, a milestone for a new social dynamic in New York City, one in which people of different racial, ethnic and class backgrounds could socialize — or at least pursue the same activity — together.”

Those hopes were short lived.

One day after opening, a Parks Department spokeswoman explained, “Lifeguards at McCarren pool were attacked by an unruly crowd and the pool had to close to restore order.” A Twitter user described “a gigantic brawl between lifeguards an hs [high school] kids. Full riot w ppl elbow dropping offa lifeguard chairs” and a “lifeguard assaulted, nearly drowned by a group of kids.” News accounts did not mention race, but Internet commenters wrote that the trouble was started by non-whites.

Authorities stepped up security, stationing two police officers at the pool, alongside two Park Enforcement Patrollers and 10 City Seasonal Aides. Three days after the attack on lifeguards, police tried to arrest rowdy pool goers who ignored lifeguards’ orders to stop diving and doing back flips into the pool.

In the process, Rodolfo Torres, 20, punched an officer “squarely in the face.” Another officer injured his wrist trying to subdue an attacker. Both were briefly hospitalized.

Three men were finally arrested and 10 others were removed from the pool. Police say some may be members of the gang MS-13. At least five lockers were broken into that day as well. Widespread locker theft stopped only after police officers were stationed in the locker rooms. The New York Post declared McCarren Pool a “mini-war zone.”

On July 6, NYC Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe downplayed the incidents as “isolated,” calling the pool a “calm oasis,” and saying “I don’t buy for a minute that it’s racial or economic tensions [causing the problems].”

That same night, a mob of about eight Hispanic teenagers attacked a 16-year-old black Hispanic across the street from the pool. They bashed his head with a brick, beat him with bats, stabbed him repeatedly, and slashed him with a broken bottle. Witnesses say the gang “seemed hell bent on killing this kid.”

The mob fled when people appeared. A passerby then pretended to help the bloodied victim to his feet, only to punch him repeatedly in the face. Three Hispanics were arrested and charged with attempted murder.

Five days later, 13-year-old Sara Puk was attacked after an argument with several older black girls at the pool. Sensing trouble, she and two friends changed and left the pool, but the black girls followed them into the parking lot.

“I was scared,” says Miss Puk. “It was five against three.” One of the girls came up to Miss Puk, saying “I’m going to hit you and I’m just going to walk away.”

Sara and her friends ran, but the black girls caught up. Eva Hawley, 16, caught Sara by the arm and punched her in the face, breaking her nose. The entire incident was recorded and posted on YouTube in a video titled “Alicia fight this white girls,” but has since been taken down. In the video Miss Hawley was reported to be “jumping up and down, hysterically, laughing.”

The attackers later made another video (also removed from YouTube) of Miss Puk holding a towel to her bleeding nose. One assailant ripped the towel from her face, exclaiming “Whoa, you fucked her up good. You’re the baddest bully, you’re baddest bully. You got her good.”

A third video shows one of the blacks doing a victory dance:

Authorities stepped up police presence at McCarren, stationing plainclothes officers at the pool and parking a temporary headquarters vehicle nearby. By mid-July, one lifeguard said there were about 40 officers around the pool on a typical day.

This wasn’t enough to prevent a near riot on July 16, when lifeguards ordered a group of jeering swimmers out of the pool and were ignored. “It looked like they had completely lost control,” one witness said. The police stepped in and led one of the men away from the pool. “Then,” said the witness, “something obviously happened:”

He tried to resist arrest maybe, and they forced him to the ground. Then a group of people come rushing in and that’s when the cop used mace. There was a palpable tension in the air. It was a really tense, unpleasant situation.

Cell phone video captured the mayhem:

Antquan Lomax, 23, was charged for pushing an NYPD deputy inspector. Ronald Crouthers, 24, and Jamaar Gordon, also 24, were charged with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest.

By month’s end, there had been more violent-crime arrests at McCarren Pool than the city’s other 52 pools combined. Former Parks Commissioner Julius Spiegel blamed the trouble on an “unusually hot summer.”

But violence wasn’t the only problem.

Just over a week after the pool opened, swimmers had to get out of the water when, as one lifeguard described it, poop was “scattered everywhere.” Another said, “I saw one kid step on a piece. I tried to tell the parents to get out, but no one listened to me. I had to yell at them that there was feces in the pool.”

Park officials said a baby’s diaper had come loose, but a police officer who saw the offending specimen had a different view: “That was no baby diaper,” he told the NY Daily News, “It was a big piece of shit!”

Less than a month after, the pool was closed for over 24 hours after a “brown cloud” of “loose stool” was sighted in the water. Days later, the pool was shut down again because of vomit in the water.

Meanwhile, locals were left to cope with the mess accumulating outside the pool, as long lines and scarce bathrooms prompted some pool goers to relieve themselves in public, tag walls with graffiti, and scatter litter.

Meredith Chesney, who owns a beauty salon near the pool, woke up one morning to find graffiti on her security gate. “I thought, ‘O.K., it’s Brooklyn, it’s not that surprising,’ ” she said. “But then, 30 minutes later, I went outside to water my plants and I found someone had defecated right in front of the salon. It’s shocking.”

One cashier at a local coffee shop said that when the pool closed each day at 7:00 pm, groups of rowdy teenagers would take over nearby stoops and steal from local businesses.

Reactions

Greenpoint residents have had mixed reactions to the pool’s rebirth. Longtime residents such as Tony Otero, 71, who has lived near McCarren Park for 25 years, felt vindicated. “It’s not good for the community,” he said, “It’s trouble. All kinds of kids are coming here.”

Some residents were pleased that a long-time eyesore had been renovated, but did not believe they would get much use from it. “There’s just too much of a criminal element here,” one young mother explained. “It’s a beautiful pool, but I would never take my 2-year-old daughter here.”

One lifeguard confessed:

Every morning when I wake up, I pray for rain. Because if it’s sunny and 90 degrees at 11 a.m., when my shift starts, there will be 1,500 people lined up around the block to get in and just 30 lifeguards to watch over them. And a lot of them are coming in drunk and high.

By summer’s end, Mayor Bloomberg was giving himself a tenuous pat on the back, reading a September 7 NY Daily News article aloud on the radio. The article said reports of mayhem were “beyond wildly exaggerated” and called the pool “a New York gem.”

The mayor had dismissed earlier reports of violence at McCarren, chiding one reporter who asked if any extra precautions would be taken to ensure safety. “We’re going to put a cop next to every lifeguard, would that help you?” the mayor asked sarcastically. In fact, this is almost what he did. The New York Times reports that by the end of the summer, an average of 18 officers patrolled the pool every day.

Now summer has ended, school has started, and the pool has been drained. But next year, the summer heat will return, and the “youths” won’t be far behind.