The Derek Chauvin Trial — Day Seven

Anastasia Katz, American Renaissance, April 7, 2021

Editor’s Note: See our coverage of the first day of the trial here, the second day here, and the third day here, the fourth day here, the fifth day here, and the sixth day here.

April 6, 2021: Former New York Gov. David Paterson joins representatives of the Floyd family at the Hennepin County Government Center in Minneapolis where testimony continues in the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. (Credit Image: © TNS via ZUMA Wire)

Court began with a hearing without the jury present. The lawyer for Morries Hall, the man who was in the passenger seat when police came to arrest George Floyd, wanted to quash (invalidate) the defense subpoena for him to appear in court. George Floyd’s girlfriend had testified that they bought illegal drugs from Morries Hall. Mr. Hall now wants to invoke his 5th-amendment right not to incriminate himself by testifying. His lawyer told the court that any activity on May 25th, both before and after police arrived, could incriminate Mr. Hall:

There is an allegation that Mr. Floyd ingested a controlled substance as police were removing him from the car; a car that has been searched twice, and from my understanding, drugs have been found in that car twice. This leaves Mr. Hall potentially incriminating himself into a future prosecution for third degree murder.

The charge would be: “Whoever, without intent to cause death, proximately causes the death of a human being by, directly or indirectly, unlawfully selling, giving away, bartering, delivering, exchanging, distributing, or administering a controlled substance.”

Morries Hall is appearing via Zoom. His attorney is in person. #DerekChauvinTrial pic.twitter.com/XPWEIInrWP

— Ana Lastra (@AnaViLastra) April 6, 2021

Derek Chauvin’s defense lawyer, Eric Nelson, agreed to submit proposed questions for Morries Hall and his lawyer to review. A decision on his testimony is expected in the coming days.

After the jury was called, Sgt. Ker Yang, a Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) Crisis Intervention Training Coordinator, took the stand. He defined “crisis” as “any event or situation that is beyond the person’s coping mechanism or beyond their control.” The goal is to bring a person in crisis back to pre-crisis level. Examples of crisis include mental health emergencies, reactions to a car crash, drugs, intoxication, etc. According to MPD policy, officers should try to de-escalate a person in crisis, when it’s “safe and feasible.”

First witness called by the state is MPD Sgt. Ker Yang. He’s the crisis prevention training coordinator. #DerekChauvinTrial pic.twitter.com/PuKe22kRJY

— Ana Lastra (@AnaViLastra) April 6, 2021

Sgt. Yang remembers that Mr. Chauvin attended one of his training sessions. The MPD hires professional actors for crisis intervention training. They act out roles in which police officers deal with simulated real-life crises. Training also includes a decision-making model with five basic steps:

- Information Gathering — Can be based on a dispatch or officer’s observation. “Listening is key.”

- Threat/Risk Assessment — Assess risk based on information.

- Authority to Act — Based on policy and city statutes for use of force, crisis intervention, and de-escalation.

- Goal and Actions — See if the person needs help and what kind of help.

- Review and Reassess — See if your technique is working, and if not, adjust it as more information becomes available.

Sgt. Yang believes this is a useful model, and that it can be used in a quickly changing situation. The sergeant said he thinks his training works.

On cross-examination, Sgt. Yang said that the critical decision-making model itself is not policy. Mr. Nelson asked if crisis intervention means the officer has to consider that it could become a crisis for bystanders, and the sergeant said that is correct, acknowledging that when police use force, it can “look bad” to the public, even if the officer’s actions are lawful. Therefore, the behavior of onlookers is part of decision-making. Officers are trained to look for signs of aggression in a suspect and observers, such as: standing tall, muscle tensing, getting red in the face, and raised voices. Mr. Nelson emphasized that an officer has to consider the “totality of the circumstances” when making decisions, a point he has brought up with previous witnesses.

Sergeant Yang said that a “crisis” could include an overwhelming event, such as seeing something upsetting, or taking drugs. The sergeant agreed that an officer may have to deal with several people in crisis at once and has to consider everything when he takes his next steps. Mr. Chauvin was dealing with many people in crisis on the day George Floyd died. As the level of crisis intensifies, the risk to the officer rises. An officer is trained to stay calm, not let anyone get too close, appear confident, and avoid staring at people. What an officer hears, such as people making threats, goes into his decision making.

The defense emphasized that according to MPD policy, in a crisis, all decisions are about what is “safe and feasible.” The prosecution emphasized that an officer always needs to keep in mind his legal “authority to act.”

Next on the stand was Lt. Johnny Mercil, a MPD use-of-force instructor who knows martial arts, particularly Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. Jiu Jitsu often uses body weight instead of striking to apply force. Documents shown in court prove that Mr. Chauvin took training from Lt. Mercil in 2018.

Lt. Johnny Mercil is now testifying. He’s explaining his job background, education, career in MPD. #DerekChauvinTrial pic.twitter.com/OLvdHJtLnI

— Ana Lastra (@AnaViLastra) April 6, 2021

The lieutenant’s testimony began with a definition of use of force:

Any intentional police contact involving:

- Any weapon, substance, vehicle, equipment, tool, device or animal that inflicts pain or injury to another.

- Physical strikes to the body.

- Physical contact to the body that inflicts pain or injury.

- Restraint applied in a manner or circumstance likely to produce injury.

Lt. Mercil added that use of force must be reasonable when it starts and when it stops. As levels of resistance decrease, the officer should decrease use of force. Police officers are taught to use the least amount of force for any purpose, such as putting people in handcuffs. Policy states that “a peace officer making an arrest may not subject the person arrested to any more restraint than is necessary for the arrest and detention.”

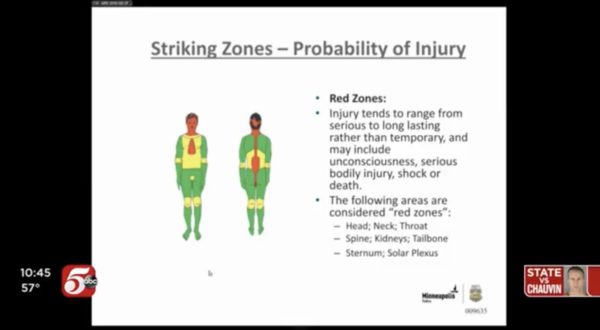

The jury was shown an image of the human body used to train officers on where they should or shouldn’t hit a suspect. The head, neck, spine, and tailbone were in the “red zone,” meaning that “injury to those areas tends to range from serious to long lasting, and may include unconsciousness, serious bodily injury, shock or death.”

(Credit Image: Screengrab via @AnaViLastra on Twitter)

This expert witness confirmed that MPD policy allows neck restraints. In general, a neck restraint is considered non-deadly force. It puts pressure on the side of the neck to slow blood flow to and from the brain. Light to moderate pressure is a controlling technique, and maximum pressure can make a person blackout.

Lt. Mercil said that he taught police officers to put the subject’s neck in the crook of the arm, and apply pressure with the forearm and upper arm. He never taught anyone to use a knee in a neck restraint. He did train people to use a leg, but to apply pressure with the thigh. Police officers may use conscious neck restraint against subjects who are actively resisting. The unconscious neck restraint may be used only:

- On subjects who are actively aggressive.

- For life-saving purposes.

- In order to gain control of an actively resisting subject and if lesser attempts at control have been or would probably be ineffective.

A neck restrain is not authorized on someone who is not resisting. When Lt. Mercil was asked to give his opinion of the photo of Mr. Chauvin with his knee on Floyd’s neck, he said it is not the kind of neck restraint MPD trains officers to do, but that it is authorized. When asked how long this technique should last, Lt. Mercil said that it would depend on the type of resistance from the subject. He said it would not be authorized if the subject were handcuffed and under control. Lt. Mercil said that a “choke hold” is considered “deadly force,” but that in the video he saw, he did not see Mr. Chauvin use a “choke hold” on Floyd.

Lt. Mercil explained that handcuffs go on one cuff at a time, and when the officer has control, he needs to check the fit and the double-lock. The double lock prevents further tightening — for the comfort and safety of the arrestee — and keeps the cuffs closed. Lt. Mercil said that when someone is handcuffed face-down, he teaches officers to use a knee to control the subject’s shoulder. “You put one knee on each side of the arm, so one would be on the upper shoulder and one would be one the back. And then isolate the arm, present the arm for cuffing.” He added that when the subject stops resisting, that is not necessarily the time to remove the knee, because people can still thrash around and be a threat. “They can kick, bite, and some other things. So control doesn’t end with handcuffing.”

He also said that once the subject is compliant, that’s a good time to remove the knee. After that, an officer should get the subject in another position, such as the “side recovery” position, which allows better breathing, or let him stand or sit. Prosecutor Matthew Frank asked, “How soon should you place the person in side recovery?” Lt. Mercil said, “When the scene is Code 4 and you’re able to do it. . . . The sooner the better.” (Code 4 means that the scene is safe.)

The lieutenant also testified about “maximal restraint technique,” or the “hobble,” in which an officer ties the legs of the subject so he can’t kick. The officer should then puts the subject on his side. “When you restrict their ability to move, you restrict their ability to breathe.”

Lt. Mercil agreed with the defense that people make excuses when they are arrested. In the past, he had had to decide if a suspect was making excuses or was really having a crisis. He arrested people who claimed to be having an emergency and said, “I can’t breathe” to avoid arrest. Sometimes Lt. Mercil thought they were lying.

Mr. Nelson showed the lieutenant a photo of a paramedic checking George Floyd’s carotid pulse by feeling the side of Floyd’s neck while Mr. Chauvin still had his knee on him. “In your experience, would you be able to touch the carotid artery if the knee was on the carotid artery?” Lt. Mercil replied, “No, sir.”

The defense then showed a screenshot from one of the officers’ body cameras, that showed Mr. Chauvin holding Floyd down. Lt. Mercil agreed that Mr. Chauvin’s shin appeared to be across Floyd’s shoulder blade, not on his neck. There were two other screenshots with different time stamps that also showed Mr. Chauvin’s shin across Floyd’s shoulder blade.

When he looked at a fourth photo that showed Mr. Chauvin’s knee, the lieutenant said this seemed to be a “hold,” not a neck restraint. He conceded that it’s possible he had to hold someone down for 10 minutes in his own police career, and that he had held people down while waiting for Emergency Medical Services. He has trained officers to do this.

The court viewed photos from a training manual that show an officer putting a knee on a subject’s shoulder, with his shin across the neck. This is a technique for handcuffing someone in a prone position. An officer may need to stay in that position for a while, but Lt. Mercil said that officers must be mindful of the neck. He also testified that he had been taught that if someone can talk, he can also breathe.

The next expert witness, Nicole MacKenzie, a MPD medical support coordinator who trains officers in first aid, said that she does not teach that if someone can talk he can breathe. She said it’s possible that a talking person may not be breathing adequately. Mr. Chauvin attended one of her courses, which included CPR training, a Narcan (antidote for certain drug overdoses) update, and casualty care.

(Credit Image: © Pool Video Via Court Tv via ZUMA Wire)

Miss MacKenzie said the department’s policy is that you need to give CPR and call an ambulance when someone is in critical condition. She went over steps for treating an unresponsive person. If he has no pulse, officers are trained to do CPR. They may stop if the situation is not safe or if they are exhausted and cannot continue.

Miss MacKenzie talked about “agonal breathing,” which is gasps that do not give someone enough oxygen. She called it “the brain’s last-ditch effort to get air.” She told Mr. Nelson that agonal breaths can be misinterpreted as effective breathing, and it’s easier to make that mistake if there is a lot of noise and commotion.

She was asked if she was familiar with “load and go,” which means putting a patient in the ambulance and leaving as quickly as possible to treat him elsewhere. This is what paramedics did with George Floyd. Miss MacKenzie agreed that the people in the area affect an EMT’s decision to load and go. Miss MacKenzie said this happens if you have a very hostile crowd. “Bystanders sometimes do attack.” She said hostility is “a growing contingent of people . . . yelling, being even verbally abusive to those that are trying to provide scene security.”

The last witness of the day was Sgt. Jody Stiger, a black use-of-force expert from Los Angeles whom the state paid $13,000 to review video, reports, and MPD manuals. He said Mr. Chauvin used excessive force. The prosecution did not finish direct examination, so Sgt. Stiger will probably be the first witness tomorrow.

(Credit Image: © Pool Video Via Court Tv via ZUMA Wire)

This was a good day for the defense. The prosecution witnesses who were supposed to be proving homicide or manslaughter beyond a reasonable doubt said what they were supposed to say on direct examination, but on cross-examination they conceded many points that were useful for the defense. Nicole MacKenzie, who gives first-aid training, was so favorable for the defense that Eric Nelson told the court he intends to call her as a witness when he puts on his case in chief.