Italy Goes to the Polls

Nicholas Farrell, American Renaissance, March 4, 2018

pOne sentence in a shining jewel of a novel by the Sicilian aristocrat Giuseppe Tomaso di Lampedusa about Italian reunification has become a proverb that defines modern Italian politics: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.” During the Fascist era, things really did change, for once, in this impossibly beautiful country, which is so very difficult to govern, but those few words from Il Gattopardo — perhaps the greatest Italian novel ever written — are a good starting point.

The Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, comparing himself to Michelangelo and Italians to marble — the raw material the Renaissance genius used to fashion his sculptures — once complained to German journalist Emil Ludwig: “It’s the raw material that I lack. Governing the Italians is not impossible. It is useless.”

Since the fall of Il Duce in 1945, Italy has had 65 governments, and today the Italians return to the polls to choose the 66th. Incredibly, for non-Italians at least, since the media tycoon and four-time prime minister Silvio Berlusconi was forced to resign in November 2011 at the height of the Eurozone debt crisis and the “Bunga Bunga” sex scandals, Italy has had four Prime Ministers, none of whom was actually elected.

The last time Italians voted in a general election was in 2013. No party got anywhere near a majority of the votes but the post-communist Partito Democratico (PD) won the most seats — barely — and was able cobble together a government led by a compromise candidate.

Then, Matteo Renzi, Mayor of Florence, was voted leader of the PD. With Italy mired in economic recession, the party had at last decided to modernize and get rid of the worst aspects of its communist heritage, as Britain’s Labour Party under Tony Blair had done in the 1990s. Mr. Renzi, whose nickname was “Il rottamatore” (Demolition Man), and who was not even an MP, became prime minister in February 2014. He was going to drag the PD out of the past and the Italian economy out of the crisis.

Nothing much changed, of course. But the global liberal elite loved the Renzi rhetoric about “reform” and “modernization,” and how “fantastico” the EU and the euro are. President Barack Obama invited him to be guest of honor at his last White House state dinner in October 2016, where he praised the “bold” and “progressive” leadership of “one of Europe’s most promising young politicians.”

Two months later, Mr. Renzi lost a referendum on his ill-judged plan to reform the Italian Senate and resigned. His foreign minister Paolo Gentiloni thus became the new unelected Italian prime minister. But Mr. Renzi has not — as he promised he would — gone away. He is still leader of the PD and he — not Mr. Gentiloni — is its candidate for premier.

Italy’s economy remains in bad shape and its migrant crisis — which since 2014 has seen the arrival of more than half a million illegal migrants by sea from Libya — remains unsolved. Nearly all these migrants were picked up from small people-smuggler boats just off the coast of Libya by NGO and EU naval vessels, which then ferried them 300 miles across the Mediterranean to Italy, even though the first safe port is in Tunisia.

Most newcomers — as even the holier-than-thou UN admits — are economic migrants and not refugees, and there are now 630,000 of them in Italy in a state of limbo. Virtually none ever gets deported.

In the 2014 Euro elections, the ruling PD with Mr. Renzi as premier won 40 percent of the vote, but now it is polling at 22 percent. It has failed to solve Italy’s migrant crisis or improve Italy’s economy. Italy’s GDP picked up in 2017, with growth of 1.4 percent — the highest since 2010 — but that was still the lowest GDP growth in the Eurozone, and Italy’s GDP is still well below what it was before the Great Banking Crash of 2007/8.

Italy has the third-oldest population in the world, and one of the lowest fertility rates (1.3 children per woman). It has the world’s fourth highest sovereign debt as a percentage of GDP (132 percent), which costs €70 billion a year in interest payments. Its banks are highly vulnerable, since they hold a higher proportion of toxic debt than banks in any other European country.

The official unemployment rate remains stubbornly high at 11.9 percent, well above the EU average, but the real rate is at least 5 points higher still, since the official one does not include hundreds of thousands of Italian workers in companies on the verge of bankruptcy, that is to say, still employed but paid not to work. Youth unemployment has come down from a high of 45 percent five years ago but is still 35 percent. Not many more than half of Italians of working age actually work — at least officially.

Yet Italians muddle through, somehow, thanks in part to the black economy in whose arts they are the world’s best. Yes, Italy has given us depressing concepts such as “Mafia” and “Ponzi Scheme,” but also inspiring ones such as “Latin Lover,” “La Bella Figura,” “La Dolce Vita.”

But the Italians, like everyone in Europe and probably more so, are sick to death of politicians and their promises. And — again like so many in Europe — they have lost faith, especially if they are under the age of 40, in the ability of the political center to provide solutions. According to the last opinion polls before the black-out that comes into effect two weeks before each election day, 34 percent of Italians had not decided whom to vote for or even if they would vote.

With the ruling PD discredited and split in two — between the majority within the party who follow Mr. Renzi and those who despise him who have formed a breakaway party — the leading party remains an anti-party that calls itself a movement: the Movimento Cinque Stelle (“Five Star Movement,” or M5S) whose slogan Vaffa! (Fuck off!) applies more or less to everything that is not wind farms and la decrescita felice (happy economic decline).

The M5S is run like a branch of the Scientologists via the internet and refuses, in theory at least, to form a coalition with any other party since parties and parliament are corrupt. Its solution, if its gets the chance, is to replace both parties and parliament with direct democracy via the internet. It has been leading the polls at 27 percent, but will not be able to form a government alone.

Founded by the bearded comedian and demagogue Beppe Grillo in 2008, the M5S claims that it stands for an end to the dishonesty and corruption of Italian politics, yet to take just the most high profile example, its mayor in Rome, Virginia Raggi, is due to go on trial in June for false testimony.

Five Star Movement founder Beppe Grillo speaks during the finally rally ahead of the elections. (Credit Image: © Donatella Giagnori/Eidon Press via ZUMA Press)

Then, in February, it became mired in a big new scandal after a national TV program exposed many of its MPs as hypocrites and liars. The movement’s rules require its parlamentarians to donate half their salary to a government small business fund, but the program’s journalists discovered that a lot of M5S parlementarians are simply signing checks to hand over the money, providing photocopies as proof, and then cancelling the checks!

Italian politicians are the highest paid in the civilized world, and receive 60 percent more than the EU average. Their salary is €15,000 a month gross plus €3,500 a month for expenses, plus all sorts of mind-boggling perks such as €1,100 a month for travel, even though they get free travel in Italy anyway, plus a fabulous pension after just one term in office!

This infuriates Italians, who know that an unskilled Italian worker gets €1,500 – €2,000 a month gross. Despite constant talk for years of doing something about this, nothing changes.

Considered as a single unit, the Coalition of the Right leads the polls. It is composed of Mr. Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (16 percent), the populist Lega Nord (14 percent) led by Matteo Salvini, and the post-fascist Fratelli d’Italia (5 percent), plus a small centrist group. Together, they are polling about 37 percent. However, under a new electoral law passed by the outgoing administration designed to guarantee strong government but destined to have the opposite effect, a party or coalition must get at least 40 percent of the votes to win a majority of seats.

Giorgia Meloni (L), leader of Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) party, Silvio Berlusconi, President of Forza Italia (Go Italy) and former Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Salvini, leader of Lega Nord (North League) party, and Raffaele Fitto, leader of Noi con l’Italia (We with Italy). (Credit Image: © Michele Spatari/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

There is therefore the probability that no group will get 40 percent and that the next government will have to be a coalition of enemies: either Forza Italia (minus Lega and Fratelli) togegher with the PD, or even the Lega and M5S, since both are populist and hostile to the euro, the EU, and illegal migrants. Or else — and God help the Italians — there will be new elections.

Only Mr. Berlusconi’s coalition has a chance of achieving the 40 percent. This is because in February, Italy’s migrant crisis became the number-one issue of the campaign. An 18-year-old Italian girl was murdered in the small hill-top city of Macerata in Le Marche, which has become an alternative and less overrun Tuscany for wealthy foreigners who own Italian farmhouses as holiday homes. The girl’s chopped-up remains were found inside two wheeled suitcases left by the side of a road. Three Nigerian migrants are in custody accused of the horrific murder.

In revenge, a lone fascist lunatic drove around Macerata a couple of days later shooting black migrants from his car and wounded six (none fatally). He was arrested draped in the Italian flag after he did a Roman Salute in front of the Monument to the Fallen and gave himself up. The girl’s murder caused national outrage in Italy among ordinary Italians, but the subsequent shootings gave Italy’s Left and the global media the chance to proclaim that Italy is in the grip of fascism.

Until all this, Mr. Berlusconi, who is 81, had been trying to avoid talking about the migrant crisis. He was selling himself as an EU-loving moderate who would introduce a 23 percent flat tax on income so as to get Italy working again. He also claimed to be the only person able to stop the populist M5S “sect,” as he calls it, from getting power and plunging Italy into chaos.

But in the face of the national fury over the the Macerata murder, he changed tack and began to sound like his coalition partners the Lega Nord and Fratelli d’Italia, who have always promised to stop migrants from coming across the Mediterranean, and to deport those already here. Mr. Berlusconi is now telling the nation that there are an estimated 600,000 illegals in Italy who are not genuine refugees, that their presence is a “social time bomb about to explode,” and that he, too, would deport the lot.

In Italy and abroad, the Left accuses him now, like his coalition allies, of being “fascist” which he, like them, is not. Nor are the Italians fascists. They are just sick of illegal migrants. So, following the Macerata murder — despite of the relentless media reports that Italy is about to fall to fascism — support among Italians for the Coalition of the Right has increased by 1 to 2 percent. Italians — unlike the global media — understand that the fascist shooter was a lunatic and that Italy is not in the grip of fascism.

Only 2 percent of Italians identify as fascists according to a recent poll published by the Rome daily Il Tempo, and only 7 percent call themselves racists. Italy’s fascist parties are so tiny that the biggest of them, Casapound (named after the American poet Ezra Pound who was a supporter of Mussolini), is polling at about 2 percent, but to get elected to Italy’s Parliament requires at least 3 percent of the vote. It is true that Fratelli d’Italia is a post-fascist party and already has MPs, but if it is a fascist party then Mr. Renzi’s post-communist PD is a communist party.

Ironically, the global liberal elite are now backing Mr. Berlusconi who, when he was prime minister four times between 1994 and 2011, they demonized relentlessly as the Devil Incarnate. No less a liberal than Bill Emmott, former editor of the house magazine of global liberals, The Economist, signaled this volte-face in January, when he wrote that Mr. Berlusconi’s coalition was Italy’s best bet. He was writing on a site called Project Syndicate, which is funded in part by George Soros, who sees the nation-state as the enemy.

Only Mr. Berlusconi can stop the awful, populist M5S, Mr. Emmott explained to the global community, and thus guarantee the Holy Grail of “stability.” Mr. Berlusconi even went to Brussels shortly afterwards, where Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, agreed to shake his scandal-tainted hand for the cameras. Incredible.

This is the same Bill Emmott who, as editor, ran an infamous Economist cover story in 2001 entitled “Why Silvio Berlusconi is Unfit to Lead Italy,” which is still remembered in Italy. I wonder, now that the post-Macerata Berlusconi has changed his tune on migrants, whether Mr. Emmott still backs him.

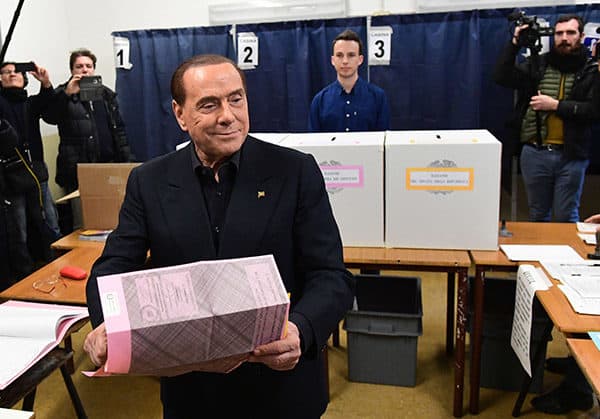

Silvio Berlusconi arrives to cast his vote at a polling station in Milan, Italy, March 4, 2018. (Credit Image: © Alberto Lingria/Xinhua via ZUMA Wire)

If the Berlusconi coalition does get the required 40 percent, whichever party in it that wins the most votes will decide the prime minister. Either way, this will not be Mr. Berlusconi, even though he behaves like a prime minister-in-waiting and is everywhere on TV and radio. Mr. Berlusconi — let us not forget — was banned from public office in 2013 after getting a four-year jail sentence for tax fraud (commuted to one year’s community service in an old people’s home).

Evviva l’Italia! (Hurray for Italy!)

May God — since Silvio il Magnifico cannot — save her.