The Rural Option for Preserving White Culture

Wolf DeVoon, American Renaissance, January 9, 2018

Three years ago, my wife and I decided to buy land in a rural, sparsely populated, all-white county in the Ozarks. We punched a road through the forest and cleared the top of a tactical hill, built a good strong house of concrete and steel. It’s foam insulated and bermed for maximum comfort, cool in the summer, and easy to heat in the winter. Our daughter is completing high school via satellite dish connected to the University of Missouri. She takes exams at an extension office in a small county courthouse 25 miles away. She and my wife joined a church, and once a week they shop in town at a WalMart, a nice hardware store, and a farm supply co-op for feed and seed.

That’s one way to preserve white culture: Bug out.

Thousands of families have done it, some choosing “the Redoubt” of Montana and Idaho. We went to a section of less frigid countryside, dotted with dairy farms and churches, not far from a city, a short drive from hospitals and industrial distributors.

Our experience has been uniformly pleasant. Neighbors are good people — not sophisticated but hard working and gentle. There’s a volunteer fire department and a shade tree auto mechanic who charges almost nothing to keep folks on the road. Electricity is supplied by a co-op. They put up two power poles for us, pulled 7000 volts across the road and up the hill to our new house, free of charge. There’s a farmers market for vegetables, seedlings, and poultry stock. Once a week, our neighbors gather at a rural general store to sit together, chat about practical matters, and tell jokes. At a nearby community center on Thursday evenings, folks attend a pot luck dinner and play guitars, fiddles, stand up bass, and sing bluegrass ballads.

Community matters to these folks, and they welcomed us as equals, despite the fact that we’re slightly different. Over the years, dozens of families came here to homestead, escaping big cities in Texas, California, Wisconsin, Maryland, Illinois, etc. The tradition here is to help one another, either as a matter of neighborliness or for a small fee if heavy equipment is needed. Building our house was a parade of “old boys” who poured concrete, did plumbing and carpentry, harvested trees we felled, split a huge stack of firewood we put up in a barn — enough to keep us warm for several years. The contractors charged reasonable rates and did great work. They are highly skilled men with families — cheerful, friendly, white Midwest Christians.

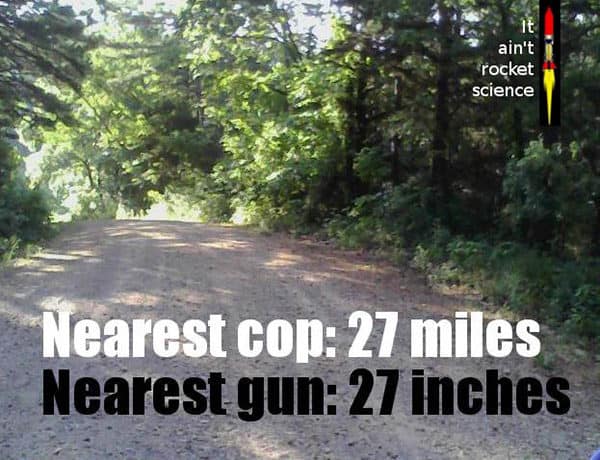

Like every rural community, we have more than a few young “white trash” meth heads and thieves. The nearest cop is at least an hour away, so we’re mindful of security. My wife and daughter have rifles, and both are trained to shoot and capable of using force, however remote that awful possibility may be. I went out of my way to put up barbed wire fences, gates and motion-detector lights, and I let it be known that I was armed and dangerous — maybe a little crazy. Good white neighbors understood and approved. They are equally stern about protecting their property and loved ones. Hound dogs hunt coyotes, to defend the dairy herds.

We made the decision to retire in a peaceful rural community after traveling the world many years, through all six continents, mostly the busy capital cities. North Africa was the worst, Indonesia a close runner-up for awfulness, Costa Rica easily the most pleasant, and Australia was likewise swell. There is a sharp line between rational white civilization and the Third World.

Dropping out of professional life was a financial trainwreck. Two years ago I had six figures in cash and credit. I spent that much buying land, wrecking part of a hillside, building the house, drilling a well, burying the septic tank and infiltrator, and everything else you need to furnish a home with. We splurged on a deluxe tiled bathroom, slightly better than a Hilton.

Our income went to zero. After the house was finished, I looked for work in three states, but found no prospect of Midwestern employment, not even as a freelance marketing writer. The past decade trimmed factories and commerce across the Heartland. The price of crude oil fell from $100 a barrel to less than $40 because of a collapse in demand. Our move to the Ozarks was accompanied by deep industrial recession. Retail is in serious trouble, malls are empty, Sears is gasping for air, about to close down. New jobs “created” in the past few years have been for bartenders, baristas, and miscellaneous minimum wage hospitality staff, working part-time at several jobs to make ends meet.

I’m too old and ugly to work as a waiter, and I’m not altogether certain that I could run a cash register at Dollar General. In a very real sense, that was a blessing, because I used the past two years and credit cards to sit in an ideal writing office, surrounded by beautiful rural countryside. The result was several hundred thousand words of fiction that I do not regret. However, all good things must end, and creative achievement is an investment, not a paying job.

Happily, I got to know my neighbors and they offered part-time work. I found that I enjoyed it: amateur carpentry, carrying trash, stacking firewood, roofing a shack, turning it into a weatherproof shop for an elderly guy to putter with a table saw. Wages are low: $10 an hour is typical, sometimes $15 for skilled work. I have power tools and hand tools, and am living a second childhood swinging a hammer, but working far slower as a balding older guy. This is the reality of rural living: a chicken coop outside and considerably less luxury.

There is a profound sense of fitness, rightness, and peacefulness, walking on land that I own. In every direction there’s evidence of work I did with my hands to improve it with fences and tighter outbuildings. The high-voltage power lines are a happy reminder of tobacco chewing roughnecks who winched heavy vehicles uphill to sink those poles and pull a ton of wire in mid-air. They’ve been back several times to restore power after a heavy storm. A tornado touched down a few miles away while we were building the house. I bugged out to a hotel, while burly white power crews worked overtime. Our completed house is tornado-proof.

The Heartland is resilient, a hard physical battle with nature. Neighbors are up at dawn, 365 days a year. I live a happy life, with cheerful kids and a hardworking wife, on a place we labored to make ours.

Supplied by the author, this image reflects his philosophy.