May 1995

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol 6, No. 5 | May 1995 |

| CONTENTS |

|---|

Selma to Montgomery, 30 Years Later

Degeneracy on the March

The Many Deaths of Viola Liuzzo

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters from Readers

| COVER STORY |

|---|

Selma to Montgomery, 30 Years Later

Events that have entered the mythology of racial heroism were not as they are usually described.

by Marian Evans

March 1995 marked the 30th anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery voting-rights march. The surviving leaders of the demonstration recently met to commemorate what was one of the most effective efforts of the civil rights era. The atmosphere was one of amity and self-congratulation, in which it was taken for granted that the marchers and their purposes were noble and their opponents were despicable racists. In an act of contrition, Joe Smitherman, who was mayor of Selma 30 years ago, presented the keys to the city to a group of aging civil rights leaders.

Rituals like this firmly establish the today’s view of who was right and who was wrong. And yet, does Mr. Smitherman, who saw the now-sanctified event as it really unfolded, not harbor even fleeting reservations about the new America that the civil rights movement created? Perhaps not. George Wallace, former governor of Alabama, recently gave a framed photograph of himself to Rosa Parks, who started the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955. He inscribed it “To a great lady.”

The 1965 demonstrations in Selma and Montgomery were part of a massive campaign to secure voting rights for blacks. In the states of the former Confederacy, it had been only during Reconstruction that blacks had had more or less uncontested voting rights. In Alabama, blacks were first given the vote under a state constitution written in 1867 by Northerners and forced upon the state by the U.S. Congress.

A new constitution, written in 1901, eliminated most blacks from politics, by limiting suffrage to people who could read and understand the U.S. Constitution, and who had been employed during the previous year or who had paid property taxes. The new constitution also required separate schools for black and white children. Since that time, as in most of the South, the vigor with which suffrage restrictions were applied to blacks varied from region to region.

In 1965, black civil rights leaders seemed to be winning every battle they fought. The Supreme Court outlawed school segregation in 1954, and the “sit-in” movement, begun in 1960, successfully integrated many Southern lunch counters, restaurants, hotels and churches. President Eisenhower used federal troops forcibly to integrate public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, and in 1962 President Johnson used them to overwhelm resistance to integration at the University of Mississippi. The movement’s greatest success, however, had been the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination in employment and public accommodation.

The national press was warmly sympathetic to black demonstrators and their white supporters. The movement basked in an aura of great moral superiority, and the obvious next step for what seemed to be an unstoppable juggernaut was to secure unrestricted voting rights for Southern blacks.

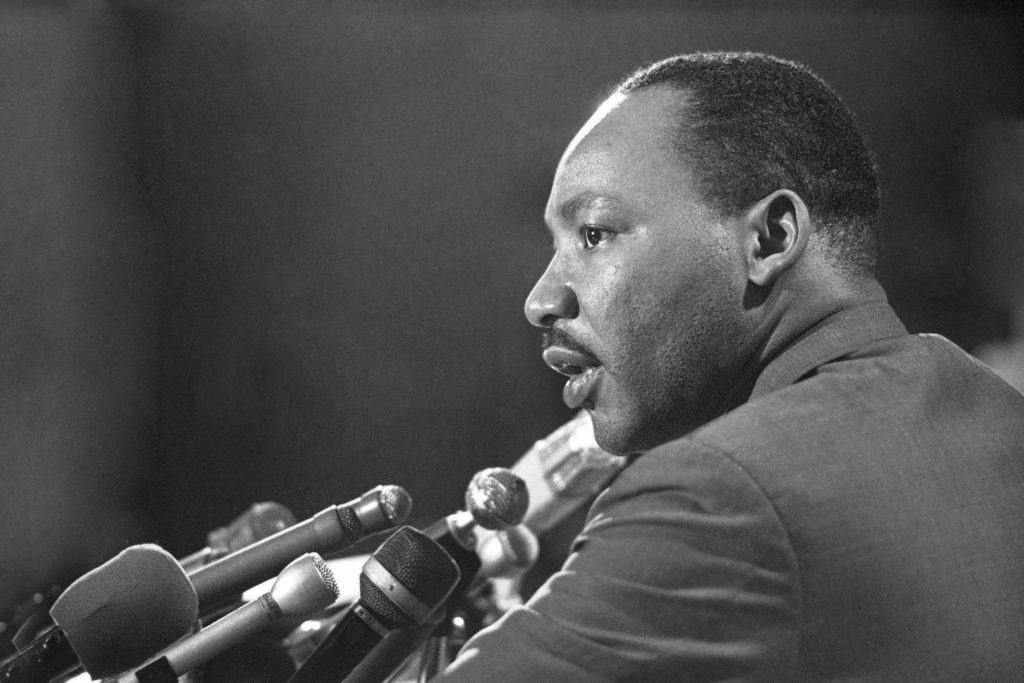

Martin Luther King, who led this stage of the movement, was by then world famous. Having come to prominence only ten years earlier during the Montgomery bus boycott, he was now a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize and a frequent guest at the White House. He chose Dallas County, Alabama as the target for demonstrations because it had been particularly inhospitable to black voters. Although there were more blacks than whites of voting age in the county, 28 white voters were registered for every black. Selma, 50 miles from Montgomery, was the county seat.

A Board of Registrars examined prospective voters, black and white. It had a small office in the Selma courthouse and could handle no more than 50 applicants a day. On January 18th, 1965, King and his close assistant, Ralph Abernathy, led six or seven hundred people to the courthouse and demanded that they be registered. There was already a line of ordinary applicants, and the group was turned away. The demonstrators marched back to their headquarters at Brown’s Chapel Church, and held a press conference, claiming — correctly — that blacks had been denied registration. Overlooked were the facts that blacks had been among those waiting to be tested and that in the days before the demonstration a number of blacks had been duly registered.

Similar nationally-reported exercises took place throughout the months of January and February. King was constantly in and out of town, flying around the country raising money and giving press conferences. He returned to give speeches and lead marches. Meanwhile, more and more northern whites trickled into town.

At the time, Selma had a population of 29,000 people, of whom 15,000 were black. It took only a small crowd to paralyze the town, and at the height of the demonstrations approximately 11,000 outsiders were swarming the streets. Selma’s mayor, Joe Smitherman, complained that for three months he spent three quarters of his time dealing with out-of-town demonstrators. Selma police were swamped with complaints of thievery, and townspeople were soon heartily sick of the visitors, many of whom were drunk and left garbage wherever they went.

Some Northerners came just to have a good time. Many were “beatniks,” who drifted across the country from one demonstration to another. They had no money for hotels which were, in any case, commandeered by the hundreds of journalists covering the demonstrations. Many whites of both sexes found accommodation in black churches and in the George Washington Carver Homes, the black housing project.

Intimate mixing of the races in this fashion was unheard of in the rural South, but even more shocking to the people of Selma was the public sexual behavior of the demonstrators. If the accounts of what can only be described as public debauchery were not given in sworn affidavits by citizens, state troopers, and national guardsmen, they would be difficult to believe (see following story). Residents of Selma could be forgiven for beginning to wonder whether the demonstrations were as much about public interracial copulation as they were about voting rights. Many of the journalists were disgusted by what they saw, and complained that candid accounts of the demonstrators’ behavior were edited out of the stories they filed.

Language as well as behavior was edited. On one occasion, James Forman, secretary of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), spoke at the Beulah Baptist Church in Montgomery. Addressing a mixed-race group that included many ministers, nuns, and church women, he said: “If the Negro isn’t given his place at the table of democracy . . . it’s time for us to knock the f***ing legs off the table.” Some of the ministers expressed surprise at this language, but Forman offered no apology.

A few minutes later, Ralph Abernathy tried to smooth things over by saying, “I’m sure that God will forgive him, that the television crews will delete it from their films, and newspapermen will not print it.” A beatnik came to Forman’s defense: “What’s wrong with ‘f**k’,” he asked; “It’s a good old American word, and expressive.”

There were demonstrations in Montgomery during this period as well. On March 10, at about 8:00 p.m., approximately 100 people were being harangued on a well-lit street a short distance from the state capitol. One of the black leaders of the group then said in a loud voice, “Everyone stand and relieve yourselves.” Practically the entire crowd, male and female, young and old, black and white, did as they were told, as rivulets ran almost to the next block. Two blacks were arrested for, according to a bystander, “particularly lewd and offensive exposure of their private parts.”

Adding to public revulsion for the demonstrators was the sight of men and women in religious garb drunk in public and fondling each other. The civil rights movement had always draped itself in religion, and King made a point of giving ministers and priests very visible roles. The presence of clerics was so useful that some of the demonstrators dressed as priests or nuns appear to have been impostors.

This may have been the case during a small demonstration in Montgomery on March 16th. A group of 34 men, most dressed as priests, arrived at the capitol late in the evening and insisted on praying on the capitol steps. Finally, at 3:00 a.m. the police let them say the Lord’s Prayer on the bottom step. As they broke up to leave, two photographers came running across the street. One of the men dressed as a priest said to one, “You stupid son-of-a-bitch, after all this time here, you didn’t get a picture of us saying a prayer on the bottom step.” An Alabama state policeman said that many of the “priests” swore like sailors and that he doubted more than half were authentic.

It may have been the disgraceful behavior of false clerics that prompted one of the three killings associated with the Selma demonstrations. On March 8th, a white Unitarian minister from Boston, James Reeb, was brutally clubbed to the ground as he left a restaurant, and died two days later. The night before Reeb died, the demonstration leaders held an all-night, out-door vigil to pray for his recovery. Disgusted journalists noted that a number of young couples at the rear of the crowd fornicated during the services.

About this time, Jimmie Lee Jackson, a black civil rights leader, was shot and wounded in an altercation with police. Activists swept him away, medical treatment was delayed, and the man died. The Chief Deputy Sheriff of Dallas County thought the delay was deliberate. “I believe they wanted him to die,” he said; “They wanted to make a martyr out of him. . . .”

The day after Rev. Reeb was clubbed, Selma demonstrators defied a court order and set out to march the 50 miles to Montgomery. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus bridge leading out of town, they were met by a line of state troopers standing shoulder to shoulder. “This march will not continue. . . .” boomed the public address system, but there was deadlock for 15 to 20 minutes, while King and his associates knelt to pray, and police pleaded with the demonstrators to go home. When officers finally moved forward with night sticks held horizontally and tried to push the demonstrators back, the resulting mayhem ended in clouds of tear gas. Eighteen officers were injured by flying rocks and bottles.

According to press accounts, the police had “whipped and clubbed” unoffending demonstrators, and television pictures showed crowds of fleeing blacks choking on tear gas. Reeb died the day after the confrontation at the bridge. These two events were a tremendous propaganda advantage for King, and they brought thousands more demonstrators to Selma from the North.

A few days later, President Lyndon Johnson went before Congress and evoked Reeb’s name in a strong call for legislation to ensure voting rights for blacks. He also ordered mobilization of the Alabama national guard to protect a second attempt at a Selma-to-Montgomery march, this one newly sanctioned by a federal judge.

Thus began, on March 21, 1965, the now-famous march. King, Abernathy, and U.N. Undersecretary Ralph Bunche — also a Nobel Peace Prize winner — took the lead down Selma’s Sylvan Street. On the way to the Pettus Bridge, the crowd marched past a record store, where an outside speaker alternately blared “Dixie” and “Bye, Bye, Blackbird.” At the head of the procession a mixed group of young men carried the U.S. flag upside down — the sign of distress. Many demonstrators wore “GROW” buttons, which stood for “Get rid of Wallace.” Nearly two thousand Alabama National Guardsmen, 100 FBI agents, 75 federal marshals, and dozens of state and county police officers guarded the marchers.

Just outside Selma, the Citizens Council of America, an anti-integration group, had set up posters showing King sitting next to known Communist leaders at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. The caption read, “Martin Luther King at Communist Training School.”

History books call this a “massive” demonstration and, indeed, some 11,000 people set off on the first leg of the journey. However, the highway to Montgomery narrowed to two lanes shortly after leaving Selma, and permission was granted for only 300 marchers on all but a few miles of roadway. Most of the crowd therefore streamed back to Selma.

Although it is impossible to know even their approximate numbers, some of the demonstrators were shills. A few openly boasted that they were in Selma because they had been offered food, money, and sex. Dora Brown’s unusual financial arrangements came to light when the checks stopped coming. In a sworn affidavit she testified as follows:

I was at Brown’s Chapel Church with the movement along with a blind man and a one-legged man who were both white people. I am one-armed and we were told at the time that we were the ones they needed worst, since we were handicapped it would help the movement. We were told that if we would make the march from Selma to Montgomery we would be paid $100.00 per month plus food and clothes… James Gildersleeve would pay us.

I have received three checks from Gildersleeve for $100.00 each but now he has quit paying me.

Gildersleeve was not to blame. Rev. Frederick Reese, president of the Dallas County Voters League, was arrested after other blacks accused him of stealing thousands of dollars in movement funds.

Miss Brown’s unhappy testimony continues: “Gildersleeve told me that he couldn’t pay me since Frederick Reese had gotten all the money. Gildersleeve gave me one pound of lard, some greens, a watermelon and $1.00 in money. He said that is all he could give.”

It is not recorded whether Miss Brown or the one-legged white man were among the select 300 who spent four nights on the road to Montgomery. It is known that the evenings were characterized by the now-usual drunkenness and fornication. On at least one occasion, police officers prevented newspapermen from photographing the revelry. And even among this inner circle, there were frequent complaints about stolen clothes and missing bed rolls.

Most of the marchers slept in the open except for King, who set up housekeeping in a trailer that was moved from camp to camp. There are no reports on how he spent his evenings, but his inclinations are now well known. His companion, Ralph Abernathy, was not a model cleric, either. In 1958, a Mr. Davis was arrested for threatening Abernathy with a hatchet because Abernathy kept trying to have sex with Mrs. Davis. She testified in her husband’s defense that Abernathy had first seduced her when she was a 15-year-old member of his congregation.

As the march went on, the press continued its adulatory, front-page coverage. All around the country, supporters held sympathy marches and worship services.

The night before the last leg of the trek, more than 30,000 people gathered in a field a few miles outside of Montgomery for a free concert. Harry Belafonte, Nina Simone, Sammy Davis, Jr., Billy Eckstein, Mahalia Jackson, the Chad Mitchell Trio, and Frankie Laine serenaded the crowd until nearly one in the morning.

On March 25, the 30,000 were joined by another 5,000 as King and Abernathy led the march into Montgomery, up to the steps of the state capitol. The city was festooned with Confederate flags, one of which fluttered along with the state flag over the capitol building. It was widely — and falsely — reported that not a single United States flag flew in Montgomery that day. The Stars and Stripes waved, as it always did, from a tall flag pole on the capitol grounds.

The leaders of the march asked to see Governor George Wallace, so they could present him with a list of grievances. He refused to meet them. The rest of the day was filled with speeches by Hosea Williams, Roy Wilkins, James Forman, Ralph Bunche and other black leaders. Joan Baez and Peter Paul and Mary were among those who entertained the crowd, which finally broke up around four p.m. The march was over. It took until midnight for sanitation crews to clean up the mountains of trash demonstrators had left behind.

Late that evening, a third killing took place when a white civil rights worker name Viola Liuzzo was shot to death as she was driving between Selma and Montgomery. Both the press and President Johnson were outraged, although accounts of the killing were often incomplete (see story, page 7).

Given the sanitized view of the demonstrations that had been broadcast to the world, Alabama congressman William L. Dickinson undoubtedly met much skepticism on March 30 when he tried to convey a different picture to his colleagues on the floor of Congress:

Drunkenness and sex orgies were the order of the day in Selma, on the road to Montgomery. There were many — not just a few — instances of sexual intercourse in public between Negro and white. News reporters saw this — law enforcement officials saw this. . . .

Has anyone stopped to ask what sort of people can leave home, family and job — if they have one — and live indefinitely in a foreign place demonstrating? This is no religious group of sympathizers trying to help the Negro out of a sense of right and morality — this is a bunch of godless riffraff out for kicks and self-gratification that have left every campsite between Selma and Montgomery littered with whiskey bottles, beer cans, and used contraceptives.

The nation was profoundly uninterested. In fact, the Selma-to-Montgomery march was probably one of the most effective events in the entire civil rights movement. Unlike the “March on Washington” in 1963, in which 200,000 people took part and where King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, the agitation in Selma and Montgomery led directly to national legislation. The nation was riveted to the march, and President Johnson constantly referred to it in his push for a voting rights bill. The killings of James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo were also a great stimulus to lawmakers.

The legislation passed and was signed into law in August, 1965. In what would appear to be a direct abrogation of the reserved powers specified in the Tenth Amendment, it prohibited all state tests of voter literacy and education. It even authorized federal elections examiners to register voters who had been rejected by state authorities, and to patrol the polls to see that such people voted. The law affected states outside the South, notably New York, which had required that voters be literate in English. New York promptly sued on Tenth Amendment grounds, but the Supreme Court ruled in 1966 against the literacy provisions — to great rejoicing among the state’s Puerto Ricans.

With a total of three deaths, the march was one of the most sanguinary episodes in the civil rights period. However, very few demonstrators were harrassed or assaulted. In retrospect, it is surprising that there was not more violence.

As invariably happens in racial matters, a group of whites with little experience of blacks saw fit to give instruction on race relations to people with a great deal of experience. Northerners invaded the South, a deeply conservative society, demanding that Southerners change their way of life. To add insult to arrogance, Northerners then proceeded publicly to violate some of the most deeply felt norms of privacy and decency. The self-control — even passivity — of the citizens of Selma and Montgomery is as astonishing as the degeneracy of the demonstrators. Perhaps even Mayor Smitherman, desperately trying to run a city overrun with disorderly demonstrators, harbored thoughts of homicide.

Now, 30 years later, Selma is a sacred name, one of the stations of the cross on the road to integration and racial equality.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Degeneracy on the March

The following excerpts are from sworn affidavits made by witnesses to the events in Selma and Montgomery in March 1965.

V.B. Bates, Deputy Sheriff of Dallas County: “To begin with, I saw white females in from other counties, other states I believe, building up their sexual desires with Negro males. After a few minutes of necking and kissing, the Negro male would lead them off into the Negro housing project. I watched this procedure many times.”

Black man, name withheld: “[M]en and women used this room [in the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee headquarters] for sex freely and openly and without interference. On one occasion I saw James Forman, executive director of SNCC, and a red-haired white girl whose name is Rachel, on one of the cots together. They engaged in sexual intercourse, as well as an abnormal sex act. . . . Forman and the girl, Rachel, made no effort to hide their actions.”

“During this same period, March 8, 9, and 10, a large number of young demonstrators of both races and sexes occupied the Jackson Street Baptist Church for approximately forty-eight hours. . . . On one occasion, I saw a Negro boy and a white girl engaged in sexual intercourse on the floor of the church. At this time, the church was packed and the couple did nothing to hide their actions. While they were engaged in this act of sexual intercourse, other boys and girls stood around and watched, laughing and joking.”

Corporal H.M. Brown, Alabama State Troopers: “I observed on many occasions the so called men of the cloth, who were white, fondling the breasts and buttocks of black female demonstrators. On numerous occasions, I saw couples of the opposite sex and color leaving the crowd, fondling each other and going into the houses and alleys along Sylvan Street.

“Since 1961, I have observed mobs and demonstrations, but the crowd of demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, was the lowest scum of the earth. This gathering of demonstrators in Selma included the largest crowd of sex degenerates that I have ever observed in one place in my life. They had no morals or scruples and did not appear to care who saw them during their orgies.”

Captain Lionel Freeman, Alabama State Troopers: “One Negro who was standing beside a priest and both standing about three feet from a line of troopers, made several attempts to provoke a trooper into hitting him. The Negro waved three dollar bills in the trooper’s face and then dropped them, saying ‘Why don’t you pick them up, I know you need it.’ . The Negro then said, ‘I’ll sleep with a white woman tonight.’ The priest seemed to think this was real funny.”

“[S]everal newspapermen who were allowed to go to the rear of the demonstration came back up to the front and told us they observed white and Negro couples in the act of sexual relations. They told us that they had sent the story and pictures home to their papers. One told me that the only thing he recognized about his story when it was printed was his name.”

Lieutenant J.L. Fuqua, Alabama State Troopers: “I also saw Negro men feel the breasts and butts of white girls, making no attempt to hide this, but rather appearing like they wanted everyone to see them.”

Charles R. McMillan, Selma policeman: “Both Negroes and white demonstrators were bedding down side by side. A young teenage Negro boy and girl were engaged in a sexual intercourse [sic] that was interrupted by a newsman who attempted to take a picture of the act.”

Selma citizen: “I, Marion J. Bass, did, on the night of the 23rd of March 1965, see at the camp site of the Selma to Montgomery march, a young white girl and a colored man having sex relations. They were on the ground out in the open and did not try in any way to hide as I walked within six or eight feet of them.

“There were many colored girls and white boys laying in the same sleeping bags. I also saw a white girl about 17 years old and four colored boys get into the back of a truck and close the doors. . . . They were in the truck about 45 minutes and when they opened the door to get out, the girl was dressing.”

Lieutenant R.E. Etheridge, Alabama State Troopers: “The action and movement of the two wrapped in the quilt left no doubt whatever that they were having sexual intercourse. They were within 30 feet of the main body of demonstrators, and in plain view of them. They remained on the ground for about 20 minutes, got up and went toward Brown’s Chapel Church.”

“On the morning of March 14th, at about 11:00 a.m. I saw a white preacher with a Negro girl in the back seat of an automobile. He had her breasts out of her blouse and was handling them.”

“I observed white ministers on at least three occasions who were in what appeared to be a very intoxicated condition.”

First Lieutenant Samuel Carr, Alabama National Guard: “I hereby further swear and attest that during such time of duty with my National Guard unit, I personally saw one case of sexual intercourse between a young white boy and Negro girl. I further swear and attest that I saw occasions of public urination. . . .”

Cecil Atkinson, resident of Prattville, Alabama: “Between Selma and the first stop, I observed both men and women relieving themselves in public, all together and making no attempt to conceal themselves at all.”

“At one point I observed a young beatnik-type man with his collar turned around to resemble a priest. He told me that it was ‘the way to get along.’ Another told me that he had been offered $15 a day, three meals a day, and all the sex he could handle if he would come down and join in the demonstration from up North.”

Mrs. Nettie Adams, resident of Montgomery: “There were white and Negro people all over the Ripley Street side of St. Margaret’s Hospital [in Montgomery on March 15] . . . . They were all kissing and hugging. This one particular couple on St. Margaret’s lawn was engaged in sexual relations — a white woman (skinny blond) and a Negro man. After they were through, she wiggled out from beneath him and over to the man lying to the left of them on the lawn and started kissing and caressing his face.”

| ARTICLE |

|---|

The Many Deaths of Viola Liuzzo

On March 25th, 1965, a woman from Michigan named Viola Liuzzo was driving along Highway 80 from Selma towards Montgomery. Riding with her was Leroy Moton, a 19-year-old local black who had become her inseparable companion during her stay in Selma. She had just dropped off a car-load of demonstrators in Selma, and was on her way to Montgomery to pick up more, when she was killed by a volley of bullets fired from a passing car. Moton was uninjured.

The Birmingham News of March 26, 1965 set the tone for the national coverage when it described her as “the red-haired, attractive Mrs. Liuzzo,” and the press widely published a photograph of her that had been taken twenty years earlier. By contrast, the coroner’s report noted that she was 39 years old and a “moderately obese white female” with needle marks in her arms and very dirty hands and feet. She was not wearing panties when she was shot, but the coroner did not examine her for recent sexual relations.

The Birmingham News also referred to Liuzzo as “a mother of five.” This was correct, but the press left out a few other facts. She had been married three times, the first marriage having lasted only one day. One of her daughters had run away from home at age sixteen, and Liuzzo herself had been arrested and fined for failing to send her children to school. In 1964, her husband had reported her missing and she later turned up in Canada. At the time she went to Selma she was under psychiatric care.

Although she had registered to vote in her home state of Michigan, Liuzzo was dropped from the rolls after a few years because she never voted. She was demonstrating for a right for blacks that she, herself, had never exercised.

President Johnson took an intense interest in her murder and within 24 hours of Liuzzo’s death went on television and radio, with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover at his side, to announce the arrest of four members of the Ku Klux Klan. Due to a mix up in timing, some of the men had not yet been arrested, and at least one listened in amazement as the President of the United States announced that he was in custody.

Johnson heaped praise on “the very fast and always efficient work of the special agents of the FBI who worked all night long, starting immediately after the tragic death of Mrs. Viola Liuzzo . . .” He did not mention that the arrests were so quick because one of the arrested Klansmen, Gary Rowe, was a paid FBI informer who had been present at the killing. Nor did he mention that the FBI had advised against sending condolences to Viola Liuzzo’s husband because, according to one bureau report, “the man himself doesn’t have too good a background and the woman had indications of needle marks in her arms where she had been taking dope.” Johnson also urged Congress to mount a full-scale investigation of the Klan, which was promptly undertaken by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

The trials of Liuzzo’s accused killers were a remarkable story in themselves — in part because of the speed with which they took place. The first trial of Collie Wilkins, the alleged trigger-man, was held in a segregated courtroom in Hayneville, Alabama, just two months after the killing.

Wilkins was defended by Matt Murphy, “Imperial Klonsel” of the United Klans of America. Women were not then eligible for jury duty in Alabama, and the one black prospective juror excused himself, so Wilkins was tried by 12 white men. The case was covered by approximately 40 newsmen, and a direct telephone line to London, England was set up in the courthouse for on-the-spot reports.

Imperial Klonsel Murphy, a third-generation Klansman, made much of the fact that the state’s case depended almost entirely on the testimony of a paid informer who had broken his oath of loyalty to the Klan to betray his brothers. “What kind of man is this,” he thundered, “who comes into a fraternal order by hook and crook, takes the sacred oath, and sells his soul for 30 pieces of silver?”

Throughout the trial, he wore a lapel button that said “Never,” which was a popular anti-integration slogan. He also tried to turn the trial into a question of white supremacy and segregation rather than of guilt or innocence. “I’m proud of my heritage; I’m proud that I am a white man,” he shouted in his closing argument; “I’m for white supremacy. The communists and the niggers have taken us over . . . Racial integration breaks every moral law God ever wrote.”

The jury’s decision was complicated by its having to decide whether the informer, Rowe, was an accomplice, since under Alabama law a felony conviction could not depend on the uncorroborated testimony of an accomplice. In the end, the jury deadlocked, ten-to-two in favor of conviction on manslaughter charges. The two holdouts later explained that they could not rely on Rowe’s testimony, since he “swore before God [in his Klan initiation] and broke his oath.” Several jurors also said they were insulted by the defense’s attempts to make white supremacy an issue in the case.

Wilkins was retried in October, 1965. Interest in the case was heightened, if that could be possible, by the HUAC Klan hearings, which started on almost the same day. Kleagles, Kludds and Kligrapps testified before a Klan-happy Washington press corps while the out-of-town correspondents descended once again upon Hayneville.

This time, the prosecutor tried to show that some prospective jurors were racist by asking them, “Do you believe a white person is superior to a Negro?” and if they believed in the inferiority of whites, like Liuzzo, “who come down here and try to help Negroes integrate our churches and schools.” Eleven of 30 prospective jurors answered that they did, but they also claimed that they could fairly consider the evidence and impose the death penalty on a man who killed an “inferior” civil rights worker. The judge ruled that the men could be fit jurors.

The total jury pool was composed of 49 whites and six blacks. Some of the blacks were disqualified because they did not believe in the death penalty or, in one man’s case, because he was a police officer. The resulting panel was all white. Klan lawyer Murphy had died in a car crash shortly after the first trial, so Arthur Hanes, former mayor of Birmingham, conducted the defense.

Once again, Rowe swore that Wilkins fired the fatal shots, but he also admitted that he, too, held a gun out the car window and pretended to shoot. For the defense, Hanes called the informer a “Judas goat” and the alleged trigger man a “scapegoat,” and referred to the trial as the “Parable of Two Goats.” Hanes also managed to find two alibi witnesses, who testified they had seen Wilkins drinking beer at a VFW Hall near Birmingham, 125 miles from the murder scene, an hour or less after Liuzzo was shot.

In his closing argument, Hanes gave no sermons about segregation or white supremacy, but the “Judas goat,” he said, “sells information for money. If there is no information, he makes — he fabricates — information and then he goes and peddles it.” Wilkins was acquitted.

Martin Luther King’s reaction to the verdict was not Gandhian. He said the civil rights movement would “possibly institute economic sanctions against communities which perpetrate such a mockery of justice. It is either this or the risk of the beginning of vigilante justice.”

The federal government then put the three Klansmen on trial in late November, in the District Court at Montgomery. This was Wilkins’ third trial in eight months. The charge, based on a Reconstruction-era civil rights law, was complicated: “conspiracy to injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate citizens . . . in the free exercise and enjoyment of rights and privileges secured them by the Constitution of the United States.” The expected arguments about double jeopardy were quashed. Once again, an all-white jury was empaneled, but the court room was integrated.

By now, lawyers and witnesses could practically recite each other’s lines, but the results were dramatically different: The jurors, mostly from small Alabama towns, found all three men guilty. The judge imposed the maximum sentence of ten years. One Klansman died of a heart attack not long afterwards, but Collie Wilkins and Eugene Thomas served full terms in federal prison.

The legal drama was not yet over; in 1966, Thomas was tried by the state of Alabama on murder charges. In the same Hayneville courthouse that had already seen two Liuzzo trials, he now faced a jury of eight blacks and only four whites. The prosecution decided not to use Rowe, their star witness in the three previous trials, because earlier jurors had disbelieved the testimony of an “oath-breaker.” Instead, the state relied on an FBI expert who explained that the bullet that killed Liuzzo could have been fired only from Thomas’ gun. Hanes once again used the alibi defense. It worked. “Jury With Negroes Acquits Klansman in Liuzzo Slaying,” was the surprised headline in the New York Times.

The case lay dormant for more than ten years before it resurfaced during investigations of the FBI’s covert Internal Security Counterintelligence Program, known as COINTELPRO. By now, J. Edgar Hoover was dead, and the program that had hired Rowe was under intense scrutiny — mainly for its infiltration of leftist organizations.

Much was revealed about Rowe. Although some press reports had referred to him as an FBI “agent,” he was nothing of the kind. The FBI had found the former bartender and night club bouncer, thought he would make a good Klansman, and asked him to be a spy. Rowe was the agency’s star informer for years — partly because he threw himself into Klan work.

Investigations in 1978 implicated him as an agent provocateur, and he was accused of helping plant the bomb that killed four black girls in a Birmingham church in 1963. Wilkins and Thomas, now out of jail, scuttled their beer-drinking alibi and claimed they had seen Rowe kill Viola Liuzzo. Rowe himself said that the FBI had approved his participation in beating Freedom Riders in 1961, and had ordered him to make internal trouble for the Klan by all possible means, including the seduction of Klansmen’s wives. Rowe even claimed to have shot a black to death during a Birmingham race riot in 1963 — though police had no record of such a killing — and that the FBI covered up his violence.

The bureau claimed this was all nonsense, and that Rowe was simply drumming up publicity for the TV-movie version (starring former Dallas Cowboys quarterback, Don Meredith, as Rowe) of his 1976 autobiography, My Undercover Years With the Ku Klux Klan. The Alabama district attorney thought otherwise. In November, 1978 a grand jury indicted Rowe for first-degree murder in the killing of Viola Liuzzo. The state initiated extradition proceedings against Rowe, who was living in Savannah, Georgia, where the FBI had set him up with a new identity.

In 1980, still fighting extradition, things got worse for Rowe. An internal FBI file came to light, which acknowledged that Rowe had led the beating of freedom riders, whom he clubbed with a lead-weighted baseball bat. The FBI paid the medical bills for Rowe’s own injuries and gave him a $125 bonus. One of his FBI handlers was found to have said, “If he happened to be with some Klansmen and they decided to do something [violent] he couldn’t be an angel and [still] be a good informant.”

Mrs. Liuzzo’s children now waded in, convinced they were on to a good thing. With the help of the ACLU, they sued the FBI for $2 million, charging that the bureau’s agent, Rowe, was at least partially responsible for the death of their mother.

Luckily for Rowe, in October 1980, a federal judge blocked extradition to Alabama, saying that a federal “agent” has rights that protect him when “placed in a compromising position because of his undercover work.” This surprising ruling was sustained by the federal appeals court.

The Liuzzo children did manage to get Rowe into court in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for their 1982 trial against the FBI. Eugene Thomas duly identified Rowe as Liuzzo’s killer but the trial judge disbelieved Thomas. He threw out the Liuzzo children’s case, ordering them to pay the $80,000 the government had spent defending itself.

Viola Liuzzo has not since been in the news. The story about the woman whose death helped spur passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act may finally have come to an end.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

Was Prof. Levin Wrong?

Some readers have complained that Michael Levin did not supply enough data in his April cover story to substantiate his view that blacks may not have developed the same level of instinctive morality as whites. Several recent developments, though strictly anecdotal, support his position.

Over Mardi Gras weekend in New Orleans, a black woman police officer, Antoinette Frank, killed three people in a hold up of a Vietnamese restaurant where she moonlighted as a security guard. She ate dinner at the restaurant before she killed two people who worked there, both of them children of the owner. Miss Frank and an accomplice also killed a policeman, Ronald Williams, who was on guard that evening. Miss Frank knew Mr. Williams, since they had worked together in the same precinct, and she shot him first. Lieutenant Sam Fradella of the New Orleans police force called the crime “beyond belief.” [Jim Yardley, Mardi Gras week ends in orgy of killings, Atlanta journal-constitution, no date or page, spring 1995.]

In March, a black man named Christopher Green robbed a post office in Montclair, New Jersey, where he had worked as a custodian. He ordered two postal employees and three customers to lie down on the floor, and shot them each several times. One of the employees recognized Mr. Green when he entered the post office and spoke to him by name, but Mr. Green shot him anyway. One of the customers survived with three bullet wounds. Police reported that Mr. Green showed no remorse and explained that he had been suffering under a “mountain of debt.” [Lisa Peterson & P.L. Wyckoff, Ex-post office worker confesses to 4 murders, The Star Ledger (New Jersey), 3/23/95, p. 1.]

Elsewhere, the Philadelphia Inquirer has written about the remorselessness with which some young Philadelphia blacks kill people.

Eighteen-year-old Kenyatta Miles shot a 15-year-old for his sneakers, but does not think he deserves to be in jail. “I killed him, but not in cold blood. I didn’t shoot him two, three, four times, I shot him once . . . I wouldn’t call myself no murderer . . . I look at my right hand ‘cause it pulled the trigger. I blame my right hand.”

Sixteen-year-old Daniel White can’t understand why he has been sentenced to life in prison for killing a stranger in a crack house. He says the victim is responsible because he did not cooperate. “If somebody see you with a gun, they gonna turn the other way — if not, they must want to get shot. I didn’t execute nobody or cut them up. I could see if somebody kill six, seven people — then they deserve life . . . I didn’t kill a lot of people . . . If I really wanted to kill the dude, I would have shot him more than once.”

Seventeen-year-old Richard Caraballo also blames his victim, a taxi driver, for complaining when he got out of the cab without paying. “I’m not a violent person. I didn’t kill nobody. He killed himself.”

Seventeen-year-old Yerodeen Williams pointed a gun at a 27-year-old white man and said, “This is a stickup.” The man hesitated for a moment and Mr. Williams shot him in the back of the head. The killer explains that the man should have obeyed. “He brung this on himself.” When his guilty verdict was announced, he shouted “F**k all of youse,” at the jury. Then he turned to the victim’s family and shouted “I’ll be back.”

Sixteen-year-old Andre Johnson was walking through Clark Park in West Philadelphia when he saw a 25-year-old graduate student coming his way. The student looked him in the eye, so Mr. Johnson felt compelled to beat him to death with a tree branch. “If your eyes meet, the dude’s looking for trouble,” he explains. What does he think about the killing now? “It didn’t benefit me. It didn’t make me feel good. It didn’t put clothes on my back. It was dumb.” [Dianna Marder, The young and the ruthless, The National Times, Feb. 1993, p. 12. (reprinted from the Inquirer)] The Inquirer found no such sentiments among whites.

FedEx Hijacking

The February 1995 “O Tempora” section included an item about a black pilot who tried to hijack a loaded DC-10 and crash it into the headquarters of Federal Express. He badly injured the flight crew, but was overpowered and thwarted. It is extremely difficult to get information on this story, which has received little national attention. However, we have learned that Auburn Calloway was convicted of attempted air piracy in late March. We have also learned that his relatives have reacted in the usual way.

“It’s one big deal of racism,” says his father, Earl Calloway. “Nobody wants to see a black dude that’s educated flying a plane.” His ex-wife, Patricia Calloway agrees. “It’s a white boy story,” she says. “They’re jealous of him. They always have been. They orchestrated this.” [Marc Perrusquia, Calloway family doubts account of FedEx attack, Memphis Commercial Appeal, no date, 1994 or 95.]

Talking on Eggs

During one of its news broadcasts, a Detroit TV station called WDIV ran a preview for a report about “most eligible bachelors,” in which a black woman said she liked “chocolate-skinned” men. This was followed by a report on a birthday party for a 415-pound gorilla at a zoo. During the subsequent on-air banter, a white weather forecaster turned to the other announcers and asked “Does that qualify as chocolate-skinned?” She was immediately fired. “Her comments last night violated our policies and clearly they’re against our beliefs,” explained the station manager. [Detroit TV weekend weathercaster fired after comparing black men to a Gorilla, Jet, 2/20/95.]

Another Casualty

In February, Catherine Webster, a high school student in Bowie, Maryland, saw six black girls beating and kicking a white girl in a school hallway. Miss Webster identified the six blacks and they have been charged with a hate crime. In March, Miss Webster was shot dead by a black man. Police think the crime may have been a failed carjacking, but they do not rule out the possibility that the killing was revenge for identifying the blacks. [Greg Seigle & Mara Stanley, Slain teen had seen assault at school, Wash Times, 3/24/95, p. A1.]

Chicago Police Exam

Last fall the city of Chicago gave an examination for policemen who wanted to become sergeants. It did not adjust the scores for race in any way, and 96 percent of the candidates with passing grades were white. Despite a blizzard of criticism from blacks and Hispanics, the city promoted only on the basis of the test scores (see cover story of October, 1994).

Mayor Richard Daley has since waffled on results of a test given to sergeants for promotion to lieutenant. As with the previous test, whites overwhelmingly outscored non-whites. Just before mayoral elections this spring, Mayor Daley announced that in addition to the 54 top-scoring sergeants (of whom 51 were white) there would be 13 “merit” promotions not based on test scores. Of the 13, six would be black and three would be Hispanic. Some of these sergeants did not even take the exam, but were selected for their “leadership qualities.”

It seems that Mayor Daley felt that just before a close election, he could not risk offending non-whites by making promotions according to test results. Ronald Burris, a former Illinois Attorney General and an independent candidate for mayor, may have got it right when he suggested that the 13 “merit” promotions were a pre-election stunt that would be reversed by court order. In any case, there have been the inevitable lawsuits, both from whites who would have been promoted and from blacks who claim the test is “racist.” [John Kass & Joseph Kirby, city will try to walk narrow line concerning lieutenant promotions, Chicago Tribune, 3/15/95, p. 7. Joseph Kirby, ‘Merit’ promotions challenged, Chicago Tribune, 3/17/95, p. 7. Bernie Mixon, Suit claims consultant bias in cop exams, Chi Trib, 3/29/95, p. 7.] Mayor Daley was re-elected.

No Mob Rule Yet

Last month we reported that several members of Chicago’s Black Gangster Disciples had entered the aldermanic elections and that two had forced runoff elections. They have been defeated. One convicted felon did win a seat on the board of aldermen, but he is not officially affiliated with the Gangster Disciples. Walter Burnett, who spent (only) two years in jail for bank robbery, defeated the incumbent, the sun of a former alderman who is in jail for corruption. [NYT of 4/6/95, don’t have full ref.]

La Raza on the Warpath

On January 13th and 14th, Hispanic activists held a huge conference at the University of California at Riverside to plot strategy in the wake of passage of Proposition 187. This is the California voter initiative that would deny social benefits to illegal immigrants and which is now blocked by a federal judge.

The speakers were a veritable ‘Who’s Who’ of Mexican-American nationalists. The majority were academics who use their positions in Chicano Studies Departments as platforms for irredentist propaganda. There were several public officials — Joe Baca, Assemblyman; Art Torres, former state senator; Cruz Reynoso, former state Supreme Court Justice; Victor Lopez, mayor of Orange Cove — as well as members of Hispanic “civil rights” organizations.

The California Coalition for Immigration Reform has produced a summary of the speakers’ remarks. (They also sell audio tapes of some of the speakers — please send inquiries to CCIR, 5942 Edinger, Suite 113-117, Huntington Beach, CA 92649.) The audience was laced with brown-bereted militants of the Aztlan movement who led cheers for dismembering the United States so that the mythical Amerindian “bronze continent” can be reborn in the Southwest.

Even the speakers who did not openly advocate secession saw the vote for Proposition 187 in explicitly racial terms. Their interests are unapologetically racial, and they take it for granted that the vote was an expression of white hostility towards all Hispanics, legal and illegal.

Former assemblyman Art Torres called the vote “the last gasp of white America.” Other participants urged legal immigrants to take out citizenship, not out of loyalty to the United States, but in order to vote against measures Hispanics may not like. Speakers frequently mentioned differential birth rates, pointing out that they will eventually win through sheer force of numbers.

Gatherings of this kind are clear demonstrations of the suicidal racial double standard whites have imposed upon themselves. Many of the whites who voted for Proposition 187 did have racial reasons; they do not want California to become Hispanic. However, they have convinced themselves that it is somehow wrong to see the problem as one of race. Hispanics recognize that race — la raza — is the central question and assume that whites, despite their denials, also think in terms of race. For so long as whites are the only group that piously refuses to think in explicitly racial terms, they will be defeated and displaced by races that know their interests and act upon them.

Lessons for Commuters

Pennsylvania Station in New York City is full of bums and winos whom Amtrak would like to remove. A black judge named Constance Motley has ruled that the railroad must leave the bums where they lie. She wrote in her opinion that Amtrak’s policy of ejecting riff raff was an attempt to spare passengers “the esthetic discomfort of being reminded on a daily basis that many of our fellow citizens are forced to live in abject and degrading poverty.” [Judge Motley’s ‘classroom’, NY Post, 3/5/95, p. 22.]

Beyond the Reach of Law

The state of New Jersey does not consider children under the age of eight capable of crime. Two seven-year-old Jersey City twins, Ali and Alquan, may change this view. One of the twins set a neighbor’s house on fire when he was only five. Since then, the two are known to have broken into and ransacked two churches, burgled a garage, started many fires, heaved a brick through a store window, and committed numerous thefts.

The police have received endless complaints about Ali and Alquan but nothing the twins do will be a crime until they turn eight. Since the mother, a former crack addict, cannot control her children, the police have begged the child welfare authorities to find a foster home. The authorities say it is hard to find foster parents for children who start fires. [Doreen Carvajal, Records as Long as 7-year-old arm, NYT, 3/9/95, p. B1.]

More Mush From Hillary

In February, Hillary Clinton spoke to the students of her former high school in the Chicago Suburb of Park Ridge. She noticed there were many more non-whites among the students than when she was there, 30 years ago.

“We didn’t have the wonderful diversity of people that you have here today,” said Mrs. Clinton. “I’m sad we didn’t have it, because it would have been a great value, as I’m sure you will discover.” [Ray Quintanilla, Chi Trib, 2/16/95, p. 7.]

More Mush From Time

In its Feb. 27 issue, Time magazine published an article about the corruption and incompetence that have been so apparent in the new, black-run South African government. This is the article’s concluding paragraph:

No matter how extensive it is, the fraud in the A.N.C. probably falls short of what was accepted under the whites-only government of the National Party. The difference, of course, is that the old regime was an oppressive, racist state that wasn’t expected to behave morally. For the new South Africa, expectations are higher. [Peter Hawthorne, The Sleaze Factor, Time, 2/27/95, p. 28.]

Hutu and Tutsi

Nine months after the massacres in Rwanda that left an estimated 500,000 dead, the country is having a baby boom. This is because the Hutu militias that did most of the killing raped just about every woman they found. According to Catherine Bonnet, a French doctor who has studied the area, many women were raped before they were killed, many were raped after they were killed, and some were just raped. Now 60 to 70 percent of the women giving birth are rape victims and do not want their children. “I hope it dies,” says one woman of her unborn child. “I don’t want to keep a criminal in my womb.” [AP, Women in Rwanda face baby boom after rapes, 2/11/95, Memphis paper (name unknown).]

What’s Up, Doc?

MGM-UA Home Video has withdrawn a video called Golden Age of Looney Tunes because one of the features is “racist.” In a 1944 short called “Bugs Nips the Nips,” Bugs Bunny goes to war against the Japanese. In one scene he passes out small bombs concealed in ice cream cones, saying “Here you go, bowlegs, here you go, monkey face, here you go, slanty-eyes, everybody gets one.” Someone from the Japanese American Citizens League complained about the video and MGM immediately took it off the market. [Hollywood’s retroactive P.C., NY Post, 3/5/95, p. 22.]

The Racial Divide

In February, the Virginia state legislature passed a strict welfare law that would require recipients to find jobs within 90 days and would cut off benefits after two years. All 13 blacks in the legislature voted against the bill and all but two whites voted for it. [AP, Virginia lawmakers OK welfare reform, don’t know paper, 2/27/95.]

The South Carolina senate has voted for the first time in its history to expel a black member, Theo Mitchell, who is in prison for violating federal tax laws. The vote was 38 to seven. All six black senators were joined by one white in voting against expulsion. [AP, Freshman led effort to turn Mitchell out of the Senate, 1/19/95, no paper name.]

The Racial Divide II

The media have discovered that blacks and whites react differently to the O.J. Simpson murder trial. A typical poll finds that 61 percent of whites but only eight percent of blacks think Mr. Simpson is guilty .

Most blacks appear to see only the racial angle. “You have to be really careful when you say ‘he’s guilty’ around black people,” says Salim Muwakil, a black columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times. “I hear a lot of middle-class black folks who usually are skeptical of conspiracy theories willing to entertain the idea of him being framed.”

Laura Washington is the publisher of the Chicago Reporter. “I talk to intelligent, successful black people all the time who sort of wink and say, ‘Well, even if he did it, he must have had a good reason,’ or ‘I don’t care if he’s innocent or guilty, let him go.’” [Kenneth Noble, The Simpson defense: Source of black pride, NYT, 3/6/95, p. A10.]

With so many blacks on the jury, a conviction is out of the question. It is amusing to imagine the tortured editorials liberal newspapers will write to justify black jurors who ignored the evidence. Of course, there will be none of the contempt they heaped upon Southern whites who refused to convict killers of civil rights activists in the 1960s.

The Racial Divide III

The most recent election for governor of Maryland was one of the closest ever. Democrat, Parris Glendenning beat Republican, Ellen Saurbrey, by only 5,993 votes. Mr. Glendennning may have gotten the winning edge because the elections administrator of Baltimore, a black woman named Barbara Jackson, knocked thousands of white voters off the rolls.

Miss Jackson has the job of keeping the rolls current, and is supposed to purge people who move away or who do not vote for five years. Just before the election, she purged 17,295 names, almost all of them in white neighborhoods. Many whites who turned up to vote were unable to do so because their names were no longer on the lists.

Miss Jackson was also in charge of security for voting machines. Records of who had access to the keys to the machines in the crucial hours after the polls closed have mysteriously disappeared. Anyone with keys could have tampered with the results. The state elections board has been unable to agree on whether an investigation should be conducted, but Congress may do its own. [Janet Naylor, Baltimore voter purge draws interest on hill, Wash Times, 3/26/95, p. A1. Janet Naylor, Baltimore voter purge appears aimed at conservatives, Wash Times, 3/25/95, p. A1.] In the mean time, the Democratic governor has proposed that minority set-asides in state contracting be increased by 80 percent. [Tom Stuckey, Glendenning asks for 80% boost in minority set-asides, Wash Times, 3/11/95, p. A11.]

Dream Team

The Immigration and Naturalization Service circulates a recruiting pamphlet called “Join the INS Team!” There are seven photographs in the pamphlet, depicting a total of 19 people. Four are white. The pamphlet notes that people who are fluent in Spanish are more likely to be hired.

Chickens Home to Roost

Madison, Wisconsin, used to be a pleasant, white, mid-western town with good schools and little crime. It was also relentlessly liberal. Since 1980, the non-white population has doubled — though it is still less than 10 percent of the population — partly because welfare payments are much more generous than in neighboring Illinois. Blacks from Chicago moved in, bringing the usual problems. In the last ten years, the number of school children on welfare has quadrupled, crime, teen-age pregnancy and venereal disease are on the rise, and crack cocaine has finally arrived.

“There’s a lot of resentment here,” says Mayor Paul Soglin. “Some of it is racial. Some of it is class. Some of it is just plain, ‘Why the hell do I have to pay for somebody else’s problem, especially when they’re from somewhere else?’” As one of the city’s public health nurses explains, “Madison has been insulated from the African-American community before all this happened. So this was new to most people. Not everyone dealt with it real well.” [Steve Mills, Madison — new promised land, Chi Trib, 3/28/95, p. 1.]

Mongrels to be Eliminated

Borneo and Sumatra have their own sub-species of orangutans, though it is hard to tell them apart. There are not many orangutans left, so zoos have been breeding them, often crossing a Sumatra with a Borneo. DNA analysis now shows that the two breeds probably diverged at least 20,000 years and perhaps as many as hundreds of thousands of years ago, and scientists have decided that they should be kept separate. All hybrids are being sterilized and zoos will breed no more of them. Some scientists call this “racism.” [Natalie Angier, Orangutan Hybrid, bred to save species, now seen as pollutant, NYT, 2/28/95, p. C1.]

Bean Pie Palace

The Nation of Islam has just spent the unheard-of sum of $5 million to build a palatial restaurant in Chicago called Salaam. The 15,000-square-foot building is in the heart of a burnt-out black neighborhood and Louis Farrakhan explains the location this way: “We placed this in the heart of the so-called ghetto to say, ‘Black people, we love you and you are worth every dime that we invest in you. This is your palace. Come here and be treated like the kings and queens that you really are.’”

Islam forbids pork and alcohol, but Salaam offers soul food, North African and Caribbean cuisine. There are actually three restaurants in the building, with the fanciest one decked out in anything but African decor: white table-cloths, marble columns and floor, crystal and brass chandeliers, and a grand piano. The Nation of Islam plans to open five more restaurants — costing as much as $2 million each — in Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, Houston, and Miami. [Lena Williams, Bean Pies have grand new home, NYT, 3/1/95, p. C1.]

Indian Takers

Of the 95 tribes that have taken advantage of their “sovereign” status and run gambling businesses, none has hit the jackpot quite like the Pequot Indians of Ledyard, Connecticut. The tribe of only 381 members owns the most profitable casino in the United States. It takes in $800 million a year in gross winnings, more than twice as much as numbers two and three — The Taj Mahal in Atlantic City and the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Foxwoods Casino, built in 1992, has already paid off its $300 million startup costs. It also employs 10,000 workers and the “sovereign” nation is not hampered by EEO laws: an Indian Preference Office ensures that Pequots and other Indians get first choice of the jobs.

Anyone who can prove he is at least one sixteenth Pequot is guaranteed a $50,000 to $60,000-a-year job at the casino, free housing, free medicine, and free tuition up to a PhD degree. Single mothers can collect their $50,000 to $60,000 if they would prefer to stay home and rear children.

During the 1970s, there were so few Pequots that the state of Connecticut nearly declared them extinct. The entire tribe is descended from a single group of five sisters who were, at one time, the sole survivors. The sisters wed men of different races, so current Pequots come in all hues and have rocky race relations.

Although the tribe is not about to fall on hard times, the glory days may soon be over. Foxwoods does a roaring business because it is the only casino in New England. The Mohegans and the Narragansetts have their eye on the swag and will soon open casinos of their own, just ten and 20 miles away. [Kirk Johnson, Tribe’s Promised Land is rich but uneasy, NYT, 2/20/95, p. A1.]

Lamar Lewis is a Los Angeles black who has been a gang member since age 13. Now 21, Mr. Lewis has spent half his life in jail for assault, attempted murder, and weapons possession. Since the age of 17, when he was shot by a rival and paralyzed, he has rolled around in a wheel chair.

Mr. Lewis still hangs out with the gang, though he admits that being a cripple is a handicap. It makes it harder to run from the police but Mr. Lewis can hot rod his wheel chair when he has to. “Nobody feels sorry for a person in a wheelchair,” he says; “You’ve got to watch your back more than you do when you’re on your feet.” Rivals don’t feel sorry for him either; Mr. Lewis’ wheel chair was nicked by a near-miss in a recent drive-by shooting. He advocates strong measures against rival gangs. “We’ve got to go over there and shoot everyone up, shoot up their children, shoot up their women . . .”

Since Mr. Lewis is disabled, he receives $604 a month in Supplemental Security Income from the federal government. The acting chairman of the emergency department at Martin Luther King Hospital in Watts estimates that Mr. Lewis will cost about $3 million in medical care and social welfare over the course of his life. [Seth Mydans, Wheelchair offers no respite for gang member, 3/9/95, p. A12.]

Dead Serious

A Fort Worth, Texas, group called Dead Serious offers a $5,000 reward to anyone who kills a criminal in self defense. The offer is open only to members, who pay $10 a year to join. Dead Serious is said to have about 800 members in 13 states. [AP, Self-Defense killings offer $5,000 reward, 2/27/94.]

| LETTERS FROM READERS |

|---|

Sir — The subject of racial differences in morality is ten times more sensitive and explosive than IQ, demanding the utmost in intellectual care. But Michael Levin steps into this minefield without a thought as to proof or demonstration.

On the basis of nothing more than a few anecdotes, he asserts that blacks are inherently morally inferior to whites. He then seeks an explanation for this unproved assertion in evolution, using unprovable speculations about prehistoric Africa to support the idea that blacks can’t help having inferior morality — their genes compel them to it.

On this insubstantial and tendentious basis, Prof. Levin then indulges in the crudest generalizations. “Since black societies never evolved formal education,” he writes, “it would make no sense for black children to be ready to internalize praise of education.” Thus Prof. Levin writes off blacks qua blacks from ever having a love of knowledge. The all-powerful god of evolution forbids it.

Blacks, Prof. Levin categorically declares, are “less empathetic than whites.” The idea of Michael Levin magisterially denying the human feelings of the entire Negro race while boasting of the superior “empathy” of his own race would be funny were it not so offensive.

“[T]he average black is, by white standards, not as good a person as the average white,” states Prof. Levin, concluding that race differences in moral outlook are therefore “perfectly good, nonarbitrary reasons for whites to wish to avoid blacks.” Here Prof. Levin has reached the goal of his endeavor: Blacks are simply less human than whites, so all whites are justified in shunning all blacks.

By its willingness to publish this egregious article, American Renaissance has discredited itself and damaged its prospects of ever reaching out beyond a small fringe. AR had offered the hope of providing something urgently needed in America — a voice that spoke in an intellectually serious and civilized way about racial truths. That hope is now in jeopardy.

Lawrence Auster, New York, N.Y.

![]()

Sir — Prof. Levin’s article on racial differences in morality reminds me of the wonderful 1968 book, Pax Britannica, by James Morris, which describes the British Empire during Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1897. Of the British colony of St. Lucia it says: “There were forty seven thousand people on the island. At least forty thousand of them were Negroes or mulattoes . . . . Rather fewer than two hundred were British, the rulers of St. Lucia . . . . of 1,824 births in St. Lucia in 1897, 1,099 were illegitimate”

That is a rate of 60 percent. Even though the times change, some things remain the same.

Orme Miller, Miami, Fla.

![]()

Sir — In the March issue you printed an “O Tempora” item about the people of Catron County, New Mexico, who are arming themselves for protection against the federal government. It doesn’t seem to me that this jibes with what the mainstream media are telling us — that people favor more gun control. The October, 1994 issue of Modern Gun says this about demand for weapons:

Ever since October, 1993, gun sales of all types have grown so quickly that the factories — all of them — are anywhere from 16,000 guns backordered for a small specialty company to 178,000 for one major company. . . . Many makers of primers and ammunition are back-ordered until June of 1995 . . . [A] small foreign-bullet manufacturer went to the SHOT show to try to sell 5 million 9mm bullets and came out after one day with orders for 97 million.

Allen Miller

![]()

Sir — In his February letter, Mr. Novak writes, “I do not see racialism and Christianity as compatible.” Let me admit that forty years ago, as a young minister, I might well have made the same statement. At the time I knew little Greek, less Hebrew, and was short on history.

What could be more racist than the Christmas story? In announcing the “God-Man,” the angel declared His pedigree. The entire third chapter of Luke traces His family tree. Matthew predicates His authenticity as the Messiah on the premise that He came from the right family, the right tribe, the right racial stock.

Christianity is founded on a New Covenant established at Calvary “with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah.” (Hebrews, 8:8) Racist? Of course it is. James wrote specifically to “the twelve tribes scattered abroad.” No foretaste at all of modern universalism.

Paul wrote to the people of Corinth that “all our Fathers . . . were baptized unto Moses.” It seems he knew something about their ancestry. Aside from the pastoral letter to Timothy, every Pauline epistle refers to the racial origins of his readers.

That is what racialism is all about: particular God-given abilities, responsibilities, and promises for a particular family, tribe, or people. If you are a Christian who reads “the Book” and knows that “all men are created equal” is not in the Bible, it is difficult for me to understand how a Christian cannot be a racialist.

Rev. Robert G. Miller