Black Rule in Zimbabwe

Arthur Kemp, American Renaissance, July 2003

Zimbabwe — when it was ruled by whites and known as Rhodesia — was the most prosperous nation in southern Africa. When black rule began in 1980, the country had excellent railroads, good highways, and clean, well run towns. It was rich in gold, chromium, platinum, and coal, and Rhodesia was such an agricultural success it exported food. It has now been reduced to a shattered ruin, facing famine, with whites and black dissenters murdered and tortured.

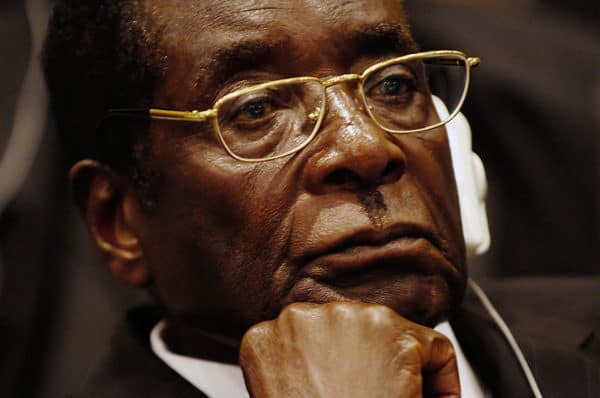

It is fashionable to blame the country’s failures on the man who has been president since 1980, Robert Mugabe. Even the famous white South African liberal Dorris Lessing writes of his “arbitrary cruelties,” and tells us “crimes have been committed in the name of political correctness.” Mr. Mugabe is undoubtedly a bad character, but so are most of the people who rule African countries. It is possible he hastened Zimbabwe’s decline but decline was inevitable once blacks took over institutions built by whites.

In the eyes of the world, black rule is so fine a thing it must never be spoiled by describing it accurately. The press therefore ignored the thievery and anti-white hatred of Zimbabwe’s new government. It looked the other way when Mr. Mugabe’s North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade killed thousands of Ndebele tribesmen for failing to support their new president from the Shona tribe. When, as early as the mid-1980s, the United Nations reported that the Mugabe government was as greedy and corrupt as any in Africa, there was silence in the West. Mr. Mugabe’s latest antics — driving white farmers off the land, and killing and muzzling political opponents — have finally forced a reluctant world to recognize him for the brute that he is.

There seem to be two additional motives beyond his usual avarice and cruelty behind Mr. Mugabe’s current campaigns. Since his government had pillaged every other source of wealth, including the mining sector, the 4,000 or so white farmers who continued to be the backbone of the economy were the only source of prosperity still available for “redistribution,” that is to say, appropriation by Mr. Mugabe’s friends. At the same time, Mr. Mugabe appears to have been deeply envious of the world’s adulation of Nelson Mandela next door in South Africa. By making one final and dramatic “anti-colonial” gesture, and by consolidating power beyond the slightest threat, he seemed to think his fame would reduce Mr. Mandela to insignificance.

Whatever the motives, in early 2000, Zimbabwe launched a program of violence and ethnic cleansing against whites, and began systematic terror against black Zimbabweans who dared to oppose the government.

Robert Mugabe

Ethnic Cleansing

The campaign against whites has been simple but effective. Truckloads of self-styled “war veterans” — the vast majority of whom are far too young to have fought the white regime in the bush war that ended 22 years ago — show up at white farms, where they camp out, get drunk, threaten the farmer and his family, and beat up black workers. The official fiction is that this is a spontaneous movement of Zimbabwean peasants who have lost patience with the refusal of whites to give up land they “stole” from blacks, but the invading convoys are clearly supported and supplied by the government. The police refuse to evict the “war veterans,” and the government has ratified the occupations by issuing decrees to revoke white ownership.

Most farmers have managed to get out alive, but 11 have not. The first two to die were David Stevens and Martin Olds. Their murders, which took place in 2000, set the tone for the ethnic cleansing that has followed.

David Stevens, who shared profits with his workers, was a member of the opposition party, Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). On April 15, 2000, Mugabe-supporters attacked him on his farm in the Macheke area, about 60 miles east of Harare. He managed to escape to police protection, but the mob of “veterans” stormed the police station and abducted him in view of the several officers who did nothing. The blacks dragged him into the bush, where they tortured him and shot him at point-blank range with a shotgun. They then mixed his blood with alcohol and drank it. Mr. Mugabe himself approved the murder, saying Stevens “had it coming to him” because of his work with the opposition.

Martin Olds, the second farmer to die, was alone on his farm 400 miles southwest of Harare. He had sent his wife and two children to relative safety with friends because of death threats. He told the local police about the threats but they did nothing. At dawn on April 18, 2000, hundreds of armed men arrived at his farm in a convoy of 14 cars and a tractor trailer. They attacked the farm house but the 42-year-old former soldier held them off with a rifle and a shotgun. He telephoned his mother, who called the police four times but they refused to intervene. At one point a rifle bullet shattered his leg. He radioed to friends: “I’ve been shot and I need an ambulance.”

Farmers rushed to his assistance, but were fired on when they approached his compound. They reported that many of the blacks were drunk. Police, who had set up a road block outside the farm, would not let an ambulance through. Mr. Olds splinted his own leg and went on fighting, wounding several attackers. The two-hour gun battle ended only when the blacks set his house on fire and forced him out. They beat him to mush and then shot him twice in the face at close range. The “war veterans” then got into their vehicles and drove away.

His widow, Kathy Olds, fled to England with their two children, a suitcase, and £60 in cash. His mother should have done the same. Nearly a year later, 68-year-old Gloria Olds died in a hail of bullets early one morning as she opened the gates to her house. Her attackers also shot her three dogs.

On December 12, 2000, a gang of “war veterans” gunned down another farmer, Henry Elsworth. He was a 70-year-old cripple, hobbling on his crutches when he was killed in Kwekwe, 125 miles southwest of Harare. His son Ian, who took five bullets in the leg and groin during the attack, said his father had received many death threats in the months before the murder, and had even left the country briefly in the hope tensions would subside.

Terry Ford, the tenth white farmer killed, had given up resistance and was actually leaving his property after an attack by 20 “war veterans.” Other “veterans” stopped his car, forced him out, stood him up against a tree, and executed him. Many other whites — men and women have been beaten, threatened, and intimidated.

The self-styled leader of the farm invaders, the late Chenjerai Hunzvi, was a prominent Mugabe supporter, who personally lead militants onto more than 1,700 farms. He actually did fight against the white regime, and liked to go by the name of “Hitler.” He was a member of the Zimbabwe parliament, and at one time was probably the second most powerful man in the country. No one worked harder to drive whites off the land. In May 2000, Hunzvi publicly urged his countrymen to seek out “British passport holders” — whom he called “ruthless, cunning people” — and force them out of the country.

“Hitler” was only following government policy. In April 2000, Mr. Mugabe told a television audience that white farmers were “enemies of the state.” In October, he elaborated on whites: “These crooks, really, we inherited as part of our population . . . We cannot expect them to have straightened up, to be honest people, and an honest community, all told . . . Yes, some of them are good people, but they remain cheats. They remain dishonest.” On August 18, 2001, Zimbabwe’s Vice President Joseph Msika explained that “whites are not human beings.”

Anyone who tormented whites or helped drive them out was therefore a great leader. In June 2001, shortly after Hunzvi died of AIDS, the ruling party politburo, headed by Mr. Mugabe, declared Hunzvi an official national hero. He is buried in Zimbabwe’s Hero’s Acre. In his funeral tribute, Mr. Mugabe said the dead man’s “leadership was particularly inspiring in that it came at an historic time.”

No doubt because he can hardly believe the British would abandon their co-racialists to death and dispossession, Mr. Mugabe is convinced Anthony Blair’s government is constantly plotting against him and is responsible for many problems. Mr. Blair has, in fact, said a few mild things against Mr. Mugabe, but has not lifted a finger to prevent outrages against whites, almost all of whom are of British stock, and many of whom also hold British citizenship.

Black Victims

There is no doubt Mr. Mugabe wants to expel whites, but the vast majority of his victims have been black. The non-partisan Zimbabwe Human Rights Forum has drawn up a list of 142 Zimbabweans killed in political violence since 2000. Only 11 were white, and almost all of the remaining 131 were supporters of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). Mugabe thugs have also killed another 115 black farm workers. Their crime is to have opposed the campaign against whites.

Many blacks who worked for white farmers were happy with their jobs, and knew ruin would follow the land grabs. Very few blacks can operate a modern, commercial farm, and when whites are run off production grinds to a halt. Any black worker who shows the slightest hint of support for whites or for the opposition MDC becomes an “enemy of the people.” The “war veterans” have operated like Maoist Red Guards, forcing farm workers to attend political rallies where they were made to identify MDC supporters. The Mugabe thugs then beat the opposition supporters or make other workers beat them. The farm invaders also love to make people sing songs in praise of Mr. Mugabe and his party for hours at a time. They have burned some farm workers out of their homes and looted many others.

In the Karoi district, black workers reported more than 1,000 cases of assault by Mugabe gangs in the two-month period of June and July 2000 alone. The police did nothing. After farmers and black workers complained, the local police chief, Superintendent Mabunda, responded with threats: “Do you want war? If you want war, I will bring troops and we can have war. I think we will have war today.”

A huge number of blacks lost homes, jobs, and access to schools and medicine, as the “war veterans” rampaged through the country, shutting down farms. Many once-prosperous farms are now looted, overgrown wrecks, and food production has plummeted. Many of the high-ranking blacks who have officially taken possession do not even pretend to farm. They live in the cities and come out for picnics.

According to the Zimbabwe Agricultural Welfare Trust (ZAWT), an organization that helps blacks suffering from the chaos of Mr. Mugabe’s polices, between February 2000 and the end of 2002, about 1,300 commercial farmers were forced to stop farming. An estimated 200,000 farm workers have lost either their homes or their jobs since the farm invasions began, and this figure does not include wives and children. The majority of displaced workers have nowhere to go. Countless thousands are now scattered around the farming areas, sometimes simply camping along roadsides with no possessions. They join the estimated 600,000 “internally displaced” people in Zimbabwe. It is not well known that a few prosperous blacks have lost farms. Anyone identified with the opposition can be treated just like a white.

The economic consequences of raping the countryside have been immense. While it is true that southern Africa is suffering from drought, there is no doubt that the food crisis now facing Zimbabwe is the result of Mr. Mugabe’s land policy. When whites could still farm freely, Zimbabwe was the breadbasket of southern Africa, and exported a range of food products. Now there are only an estimated 350 commercial farmers left, many operating under impossible conditions.

The catastrophic drop in food production means that an estimated eight million of Zimbabwe’s 13 million people face starvation, according to the UN and other international bodies. Corn meal — the staple food — bread, milk, sugar and other commodities are scarce, and long lines are common. In the Masvingo district, a BBC reporter was shocked to find Zimbabweans scratching in the dirt looking for roots to eat. Other journalists have found Zimbabweans eating rats, river silt and poisonous plants in order to fill their stomachs.

The entire economy is starving. Tobacco, once the leading export product, was largely grown by white farmers. Now, hard currency shortages mean gas stations run dry. Finance Minister Simba Makoni admits the country is bankrupt. “No one is investing in the country, nor is there any likelihood anyone will, and there is no foreign currency available to import food,” he says, in a rare display of government honesty. Food relief — the United States is a major donor — is distributed along political lines, further consolidating Mr. Mugabe’s power.

White Institutions

When black rule began, Zimbabwe still had all the institutions of Western government whites had set up, and although Mr. Mugabe has essentially dictatorial powers, he has not yet completely destroyed these institutions. For example, Zimbabwe still has elections, in which political opponents run for office against the ruling Zanu-PF party. In the early years, Mr. Mugabe could afford to hold elections with relatively little vote-rigging because he and his movement were still popular. Now he rules through force and intimidation, and opposition politics is a dangerous career.

In connection with the June 2000 parliamentary elections alone, Mugabe supporters murdered more than 30 political opponents. Dozens of opposition politicians have been arrested, assaulted, or had their homes attacked. Human rights groups charge that during the elections there were more than 19,000 cases of politically-motivated violence and torture. Since the vote, Mugabe thugs have killed another estimated 60 to 80 opposition supporters. The elections themselves were spectacularly corrupt, but still left opposition parties with 48 percent of the 120 contested seats (30 parliamentarians are directly appointed by Mr. Mugabe, so the MDC has 57 of 150 seats).

Another gift of white Rhodesians to black Zimbabwe was a tradition of press freedom, a tradition Mr. Mugabe has gradually snuffed out. During 2002, the authorities threw two journalists in jail, detained 32, and assaulted five. The offices of the Daily News, the one remaining independent paper, have been firebombed three times in the last two years. In May, police forced the last foreign correspondent, Andrew Meldrum, onto a plane and expelled him for publishing “false news.”

A once-independent police and judiciary are yet more casualties of black rule. According to the Amani Trust in Harare, which monitors human rights abuses, the police have been purged of anyone suspected of disloyalty to the regime, so that the force is now effectively another Zanu-PF militia. This is why appeals for help from whites or political opponents are fruitless, and why attackers are not prosecuted. The army and the Central Intelligence Organization — the Zimbabwe secret police, which is accountable only to Mr. Mugabe — are just as partisan. At a political rally in 2000, then Zimbabwean defense minister Moven Mahachi explained how to handle the opposition: “We will move door to door, killing . . . I am the minister responsible for defense; therefore I am capable of killing.”

All public employees soon learn where their primary loyalty must lie. In June 2001, Mr. Mugabe’s foreign minister, Stan Mudenge, told trainee teachers: “As civil servants, you have to be loyal to the government of the day. You can even be killed for supporting the opposition, and no one would guarantee your safety.”

Judges, respected and independent when they were Rhodesian, are now tools of the regime. Many magistrates are Zanu-PF-appointees or are too intimidated to act against the government. In March 2001, the government forced the country’s chief justice, Anthony Gubbay, into early retirement after he ruled against the seizure of white-owned farms. Other judges who tried to take a stand have resigned after threats to their lives and families. Courts have issued at least two orders to the authorities to clear farm invaders off private land, but the government paid no attention.

A Zimbabwean High Court judge, Ben Hlatshwayo, ignored an order by his own court barring him from moving onto a farm confiscated from a white family. In December 2002, Mr. Hlatshwayo moved onto the 900-acre farm anyway, accompanied by a police escort.

While the government ignores the courts at will, it uses the law as a weapon against opponents. The MDC leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, is on trial for allegedly plotting to assassinate Mr. Mugabe, and could be put to death if found guilty.

The causes of Zimbabwe’s misery are so clear that many people continue to risk death to oppose Mr. Mugabe. In early June, the government sent tanks into the street to put down what was to be a five-day general strike called in the hope of driving Mr. Mugabe from office.

Ben Hlatshwayo had conveniently issued an injunction against the strike, and police arrested Mr. Tsvangirai for the capital crime of treason. Police dispersed demonstrators with live fire, tear gas, and water cannon. There were hundreds of injuries, but miraculously, no one was killed.

Interest and Admiration

Although Zimbabwe’s measures against white farmers are destroying the country, and have been met with universal condemnation in the West, Africans look on with interest and admiration. Most ominous is the reaction in South Africa, which has had a less well-publicized campaign of murdering white farmers. In August 2001, South Africa sent its agriculture minister to Zimbabwe to discuss “helping understand farmer settlement,” and in October 2001, South Africa’s Deputy President, Jacob Zuma, said Mr. Mugabe had “convincingly explained his land policies.” South African Labor Minister, Membathisi Mdladlana said in Zimbabwe on January 11, 2003, that his country “had a lot to learn from President Robert Mugabe’s program of land reform.”

When Mr. Mugabe’s government expelled outspoken journalist Mercedes Sayagues, the foreign affairs spokesman for the ruling African National Congress (ANC), Ronnie Mamoepa, said he had no reason to doubt Zimbabwe’s explanation that the expulsion was not a threat to press freedom. Likewise, South African Justice Minister Penuell Maduna argues that measures taken against judges do not undermine judicial independence or the rule of law. In March 2001, Frank Chikane, Director-General of the South African presidency, announced that his government believes there are no human rights abuses in Zimbabwe. Other African countries are just as supportive. A meeting in Angola in December 2001 of African heads of state from the 14-nation Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) unequivocally backed Mr. Mugabe’s leadership, and refused to impose sanctions of any kind.

Particularly worrisome for white South Africans is the “Amendment to the Land Restitution Act” promulgated by the government on May 9, 2003, and likely to pass easily in the ANC-dominated parliament. It is an almost perfect copy of the Zimbabwean farm seizure legislation, and will give the South African Minister of Agriculture and Land Affairs the power to take urban or rural land without any judicial process if it is “in the interests of land reform.” At present, land can be “redistributed” only by court order and if there is an agreement between the current owner and the claimant of the land. The ANC clearly intends to follow the Mugabe path.

Although observers from Europe and the United States dismissed the March 2002 presidential election — won handily by Mr. Mugabe — as a fraud, the head of the South African observation team said the vote was legitimate, and that the ANC sent “warm congratulations.” Other African heads of state endorsed the elections. Benjamin Mkapa of Tanzania even called Mr. Mugabe a “champion of democracy,” and a spokesman for Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo said his government would urge Europe and the United States to accept the election results. President Daniel Arap Moi of Kenya sent his congratulations. Namibia conveyed its “warmest congratulations to His Excellency, Comrade Robert Gabriel Mugabe,” and President Sam Nujoma announced plans for a farm seizure program of his own.

The Organization of African Unity (OAU) observer team in Zimbabwe reported that “in general the elections were transparent, credible, free and fair.” By African standards, of course, the election was entirely as it should be: it kept the incumbent in power.

A wide-spread view of Mr. Mugabe was expressed in New African magazine, which is read all over the continent. Its May 2000 cover story was unequivocal: “Mugabe is Right.”

Africans everywhere seem to love Mr. Mugabe. Last September 12, after addressing a session of the UN General Assembly in New York, he accepted an invitation to speak at New York’s City Council chambers, where he gave a long talk about his land policies to a dozen or so members of the City Council’s Black and Hispanic Caucus. Charles Barron, a former Black Panther, and the council member who had invited Mr. Mugabe to City Hall, hugged him and held his hand aloft like a victorious boxer. No council member protested the visit.

South Africa offers Zimbabwe material as well as moral support, providing seed, fertilizer, fuel and transportation aid under the terms of an aid package signed in October 2002. The state-owned South African electricity and oil companies, Eskom and Sasol, supply Zimbabwe on credit — something no one else will do — and have very little chance of collecting on tens of millions of dollars worth of debt. The cost is borne by South Africans, of whom the largest number of paying customers are white. The continuing cost of ANC support for Zimbabwe has been reflected in the currency markets; the South African rand lost 25 percent of its value in 2000 alone, and has declined steadily ever since. The country’s annual inflation rate is more than 250 percent.

Mr. Mugabe will probably succeed in driving whites out of the country. Some he will force out physically, and others will leave voluntarily as Zimbabwe sinks further into Third-World misery.

There was a time, not so long ago, when whites could not have been treated this way. In 1866, Emperor Theodore of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) imprisoned a number of British subjects, claiming Britain was not showing his regime enough respect. Diplomacy failed, and the emperor took his hostages 400 miles inland to the mountain fortress of Magdala. Under orders from the prime minister and Queen Victoria, Sir Robert Napier equipped an army of 13,000 British and Indians in Bombay, loaded the men and nearly 30,000 head of livestock (including 44 elephants) onto a great fleet, and sailed across the Indian Ocean to Massowah on the Red Sea coast. It took three months to march the men through the parched, mountainous wilderness to Magdala, where Napier reduced the fort and rescued the hostages. Emperor Theodore committed suicide.

That was a time when Britain — and the white man — were not to be trifled with. Other nations took note, just as Namibia and South Africa are now taking note of Britain’s spinelessness as Mr. Mugabe drives whites off the land. Action in defense of one’s people is strictly a question of will, which the British once had but now do not. They could arrange a “regime change” in Zimbabwe with one 20th of the men they sent to Iraq, but the British are now incapable of using force to defend race and heritage.

Zimbabwe teaches several lessons. Two are all too familiar: blacks make a mess of Western institutions, and some will brutalize whites if they get the chance. South Africa will meet the same fate; it is only a matter of time. But losing southern Africa to savagery is far less important than the fact that Britain, the United States, and all other European countries are letting it happen. If the British cannot bring themselves to save their Zimbabwean cousins from white-hating barbarians, they cannot be counted on to save themselves either. If immigration continues, and dispossession comes to the home islands, there will be no mother country to ignore their pleas for help.